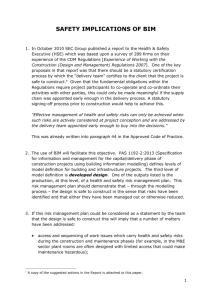

JBIM

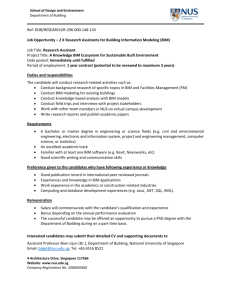

advertisement