Exploring Key Informants’ Experiences with Self-Directed Funding A Research Report

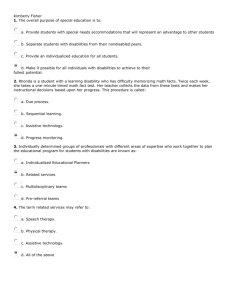

advertisement