10 Y Q L

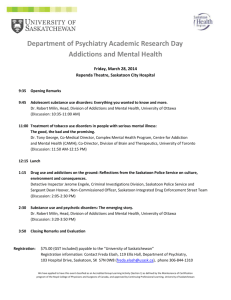

advertisement