Worker Co-operative Development in Saskatchewan

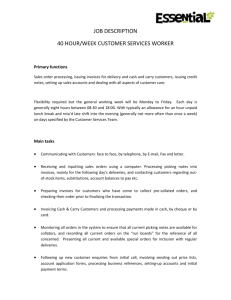

advertisement