ANTHRO NEWS Anthropology in the Professional World

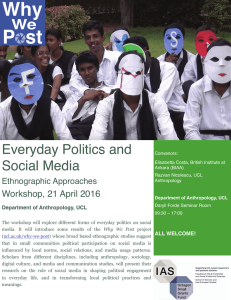

advertisement