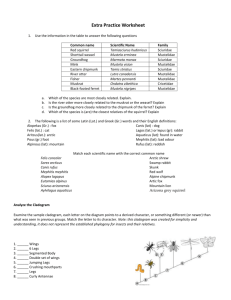

Mustela Vison

advertisement

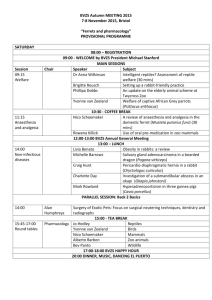

Mustela Vison Mink Mark Fields Photo © 2002 www.arttoday.com Description: Mustela vison are sexually dimorphic with males generally 1.5 to 1.8 times larger than females of the species. Length: Adult Male – 350-680 cm Adult Female – 300–450 cm Weight: Adult Male – 840-1805 g Adult Female – 450-810 g Tail Length: 14-22 cm Mustela vison have a rich dark brown coat with darker colored guard hairs over their backs with a slightly lighter color on the belly. There is usually a white spot or patch around the chin/throat area of Mustela vison but white patches may exist else where on the body particularly around the feet and belly (Kurta, 1995). Mustela vison also may display a black or silver-grey coloring and a variety of other colors exist on fur farms (Mustela, 2001). Mustela vison have long slender bodies with short legs, toes that are partially webbed and a water proof coat for living in a semi-aquatic environment. Distribution: Mustela vison are found throughout most of the Untied States and Canada excluding parts of the arid southwest U.S. (Schlimme, 2003). Mustela vison are present throughout the entire state of Wisconsin which contains a large population of Mustela vison due to the abundant lakes, streams ponds, marshes, and swamps that Mustela vison prefer. Ecology and Behavior: Mustela vison is Swedish for “stinking animal” the name is derived from the musk that the animal extrudes from its musk gland when alarmed. The smell can be compared to that of a skunk. Mustela vison prefer riparian zone habitat along bodies of water and are rarely found far from an open source of water (Whitman, 1981). Though Mustela vison have been known to venture as far as a mile from any water source in pursuit of food. Mustela vison’s home range is gender specific; females have a considerably small home range of 20 to 50 acres while a male is a drifter and may have a home range of several miles with many females with in its home range (Kurta, 1995; Mitchell, 1958). Some mark recapture studies have shown males to have moved up to 26 miles in a prior to recapture (Mitchell, 1958). Mustela vison will defend it home range tenaciously against other Mustela vison of the same gender and use their musk glands to mark their territory boundaries. In the summer months females and young will stay in family groups while the males are mainly loners. During the winter months individuals of both genders spend most of their time solitary from one another. Mustela vison is a primarily nocturnal animal that is active all year round. While mostly thought as a nocturnal animal many have been observed during the hours of dawn, dusk, and even daylight during the breeding season and are believed to be crepuscular (Whitman, 1981). Males are very active during the breeding season seeking mates at anytime of the day (Whitman, 1981). Mustela vison’s long slender body fits its style of movement very well both on land and water. While hunting Mustela vison will slink and bound searching through every crevice, log and hole with amazing speed. They also hunt in the water and are very agile swimmers diving up to 5m and traveling up to 30 m under water. Average dives usually lasting from 5-20 seconds (Poole, 1976). Mustela vison has a voracious appetite, has little fear, and are very opportunistic; Mustela vison’s diet may consist of many other species including crayfish, frogs, salamanders - Amphibians, muskrats – Ondatra zibethicus, rabbits - Leporidae, shrews, mice, rats, voles - Muridae, pheasants Phasianidae, ducks - Anatinae, rails - Rallidae, ruffed grouse – Bonasa umbellus, sand pipers, mollusks, insects and many types of fish (Dearborn, 1932; Eberhardt, 1974; Hine,1952; Waller, 1962). Mustela vison have even been found with reminisce of bats Chiroptera in their stomach (Goodpaster, 1950). Mustela vison are known to prey heavily upon muskrat populations in the winter time or at times of high populations; hunting them above ground, in the water, or even attacking them while in the den (Errington, 1943). Mustela vison have been known to make many kills and cache the animals in their dens for later consumption. One Mustela vison den was discovered that contained 13 muskrats, 2 mallard ducks - Anas platyrhynchos, and a coot - Fulica all thought to have been killed in the last 3 days (Yeager, 1943)! Though Mustela vison have been observed killing animals such as muskrats for what is thought of for mere sport and leaving them without eating any of the kill. When not hunting Mustela vison mostly live in dens along the waters edge. These dens usually have a small opening at the water’s edge and are about 3.5 m deep and 30 to 90 cm below ground with a 30cm nest cavity at the end of the den that is lined with dry grasses, leaves, and fur or feather from their prey. Mustela vison may dig these borrows themselves but are just as likely to take over a muskrat hut or den that had the occupant recently removed. Mustela vison have relatively few predators as adults but as juveniles they are forced to relocate and establish their own territories. This leaves them susceptible to large predators such as coyotes - Canis latrans, bobcats – Lynx rufus, great horned owls – Bubo virginianus, wolves – Canis lupus, and red foxes- Vulpes vulpes (Kurta, 1995). The only real predator of an adult Mustela vison is either another larger Mustela vison or a fur trapper. Mustela vison are at the top of the food chain for the most part, so they are susceptible to pollutants such as mercury, PCB’s, DDT, and other pesticides building up in their fatty tissues. Mustela vison also carry parasites such as ticks, fleas, lice, and mites. Parasitic worms are also carried by many individuals of the species (Mustela, 2001). Ontogeny and Reproduction: Mustela vison reach sexual maturity at different times based on sex: Female around 10-12 months of age; Males around 15-18 months of age. Mature Females enter into heat for 3 – 4 weeks in late winter usually from late February to early April (Kurta, 1995). Females may breed with one or more males over the course of the breeding season. Gestation generally lasts from 35 – 75 days; length shortens the later the breeding season progresses (Kurta, 1995). There are signs that delayed implantation occurs in order to coincide birth with times of high resource availability (Mustela, 2001). The female generally gives birth in late April or May in their nests. Litter size is generally 4 – 9 kits but a litter of as many as 17 kits has been recorded (Mustela, 2001). At birth the young are covered with a fine white hair and are blind. Around 5 weeks of age the eyes open and during the 5th or 6th week the young are weaned by the mother. So lactation generally only lasts for about six weeks. The juveniles are then given meat from the mother’s kills but around week 7 or 8 juveniles are making their own kills and by week 12 they are self sufficient (Kurta,1995; Mustela, 2001). The young then disperse from the mother in the fall. Females only produce one litter per year and are fertile for 7-10 years based on various studies (Mustela, 2001). Remarks: Economic Value Mustela vison has long been pursued by trappers for the value of their fur to make garments. Wisconsin is among one of the leading states in the nation for fur harvest. Even in early settlement days fur harvesting Mustela vison was a multimillion dollar business. In the early 1990’s the fur market received less demand and the value of Mustela vison’s fur in turn diminished. Recently an upswing in demand has come about and the price and demand for Mustela vison fur is once again rising. Mustela vison have been so sought after for their fur that Mustela vison ranches have come about in which about 85% of the current fur market is supplied. As of 1997 there were around 420 Mustela vison farms in the U.S. alone with many more in the UK and Russia. Wisconsin is again one of the leading states in Mustela vison fur production from ranches. The animals are raised in wire mesh cages and harvested at 7-8 months of age during which they have their winter coats. Literature Cited: Cowan, W. F., and J.R. Reilly. 1973. Summer and Fall Foods of Mink on the J. Clark Salyer National Wildlife Refuge. Prairie Naturalist 5(2):20-24. Dearborn, N. 1932. Foods of Some Predatory Fur Bearing Animals in Michigan. University of Michigan School of Forestry and Conservation Bulletin 1:1-52. Eberhardt, L.E. 1974. Food Habits of Prairie Mink During the Waterfowl Breeding Season. M.S. Thesis, University of Minnesota, St. Paul. 49pp. Errington, P.L. 1943. An Analysis of Mink Predation Upon Muskrats in North-Central U.S.. Iowa State College Agricultural Experiment Station Research Bulletin 320:789-924. Goodpaster, W., and D.F. Hoffmeister. 1950. Bats as Prey for Mink in Kentucky Cave. Journal of Mammalogy 31(14):457. Hine R.L., and B.P. Stolberg. 1952. Food habit studies of ruffed grouse, pheasant, quail and mink in Wisconsin. Madison : Wisconsin Conservation Dept., Game Management Division. pp 18-22. Kurta, A. 1995. Mammals of the Great Lakes Region. Revised edition. University of Michigan Press, Ann Harbor, USA. Mitchell, J.L. 1958. Mink Population Study. Montana Fish and Game Department, P-R project W-049-R-7, 2/Job M. 3pp. Mustela Vison – American Mink. 2001. http://212.187.155.84/wnv/Subdirectories_for_Search/SpeciesKingdoms/0Familie s_ACrM_Carnivora/Mustelidae/Mustela/Mustela_vison/Mustela_vison.html#Mea surement Poole, T B., and N. Dunstone. 1976. Underwater predatory behavior of the American Mink. Journal Of Zoology 178(3): 395-412. Schlimme, K. 2003. Mink, American Mink. http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/mustela/m._vison$narrative.htm l University of Michigan. Waller, D.W. 1962. Feeding Behavior of minks at some Iowa Marshes. M.S. Thesis, Iowa State University, Ames. 90pp. Witman, J.S. 1981. Ecology of the Mink in West Central Idaho. M.S. Thesis, University of Idaho, Moscow. 101pp. Yeager, L.E. 1943. Storing of Muskrats and other foods by Minks. Journal of Mammology 24(1):100-101 Reference written by Mark Fields, Biology 378 student. Edited by Christopher Yahnke. Page last updated.