Sorex hoyi Pigmy Shrew Description

advertisement

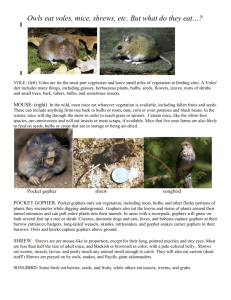

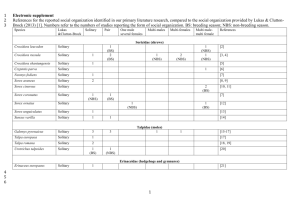

Sorex hoyi Pigmy Shrew Description The pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi) is one of the rarest small mammals in North America (Ryan, 1986). The pygmy shrew, formerly known as Microsorex hoyi, was changed to Sorex hoyi. The pygmy shrew weighs only 2.2g to 6g and has small, bright black eyes with obscure ear pinnae. The snout is constantly moving with whiskers at the end of the snout that help in feeling. The muzzle is paler in color than the back portion of the body (Long, 1974). Dorsal coloration of the fur differs between seasons. In summer, a coppery brown is present, and in winter, a grayish color is present. Ventral parts are a paler, grayish brown color with a drab copper or tan coloration. The tail is dark brown above and a paler color below. The tail is less than 40% of the total length (Kays et al. 2002). The total length of pygmy shrews varies from 67mm to 98mm in total length; the tail varies from 25mm to 34mm while the hind foot ranges in size from 8.5 to 11.5mm in size (Long, 1972). The dental formula is: 3/1, 1/1, 3/1, 3/3 = 32 (Wund, 1999). Pygmy shrews are identified by three visible unicuspids; two other cusps are present but not readily visible (Kurta, 1995). The most common vocalization pygmy shrews make is a twittering and highpitched scream used in confrontations with individuals of their own species (Macdonald, 2001). Distribution in Wisconsin The pygmy shrew has a widespread distribution ranging from the northern parts of North America to southern parts of the Appalachian Mountains. Pygmy shrews are found throughout Wisconsin, except for southwestern Wisconsin. The pygmy shrew lives in varying habitats including deciduous woods, regenerating clear-cuts, grassy fields, bogs, coniferous forests, floodplains and swamps. Ideal pigmy shrew habitat is found in moist boreal habitats (Kurta, 1995). Past studies have found that pygmy shrews like areas near water (Long, 1972). Sometimes shrews are referred to as primitive forms of life, but in actuality they are a modern family of eutherians. In North America, the earliest shrew fossils were recorded in the middle Eocene period, about 45 million years ago. Fossils found in Eurasia date back to about 34 million years ago during the Oligocene period. In Africa, shrew fossils were found from the middle Miocene period about 14 million years ago (Long, 1974). Ontogeny and Reproduction One study from western Kentucky and Tennessee concluded that based on estimated age and time of capture, the major period of parturition was January through early March. Parturition also occurred from August through December, but at a lower rate with fewer individuals born in June and July. The lack of moisture is believed to be the main determining factor of the numerical abundance of pygmy shrews; moisture affects both the water balance and invertebrate prey abundance (Feldhamer et al., 1993). Other studies have focused on tooth wear suggesting pygmy shrews give birth in every month of the year, but other studies have shown pregnant animals, especially northern pygmy shrews, have a more restricted breeding season and are limited to certain months. One study showed that females are capable of giving birth to more than one litter per year in favorable environments, with litter sizes ranging anywhere from 2 to 8 offspring (Wilson and Ruff, 1999). Female pygmy shrews have six tits while breeding males have a prominent, slit-like scent gland on each flank (Wilson and Ruff, 1999). Ecology and Behavior Pygmy shrews often stand on their hind limbs like a kangaroo and run quickly with their tail extended in a slight curve (Kays et al., 2002). Their dens can be burrows found in the roots of old stumps or under logs. In captivity, pygmy shrews repeatedly build nests of cotton with entrances at both ends (Wilson and Ruff, 1999). Predators of pygmy shrews include domestic cats, hawks, snakes and foxes. Other predators include shrews, owls and carnivores. Parasites include mites, fleas, intestinal tapeworms and ticks (Wilson and Ruff, 1999). Many shrews feed by being opportunists in their foraging habits and many show little specialization (Macdonald, 2001). Food sources for wild pygmy shrews are less known than captive species. One study from the upper peninsula of Michigan found Diptera, Coleoptera, spiders and sphagnum moss in the intestines. Another study from Vermont revealed that small grubs, earthworms and other unidentified outer parts of insects present in the stomach. Pygmy shrews from Sagamook Mountain, New Brunswick, had stomach contents of Coleoptera and spiders making up 94.3% volume of the diet found in 23 animals (Ryan, 1986). Shrews are very active requiring consumption of large amounts of food. Some species cannot survive more than a couple hours without food because of a high metabolic rate that leads to extremely high heartbeats per minute. In some shrew species, heart rates are over a thousand beats per minute. In some northern shrew species the skeleton, skull and certain internal organs shrink during the winter in order to conserve energy. Currently hibernation has not been confirmed for any shrew (MacDonald, 2001). Literature Cited Feldhamer, G. A., R. S. Klann, A. S. Gerard, and A. C. Driskell. 1993. Habitat partitioning, body size, and timing of parturition in Pygmy Shrews and associated Soricids. Journal of Mammology 74(2): 403-411. Kays, R. W. and D. E. Wilson. 2002. Mammals of North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA. Kurta, A. 1995. Mammals of the Great Lakes Region. The University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA. Long, C. A. 1972. Mammalian Species, Microsorex hoyi and Microsorex thompsoni. The American Society of Mammalogists. 33: 1-4. Long, C. A. 1972. Notes on habitat reference and reproduction in pigmy shrews, Microsorex. Canadian Field-Naturalist 86(2):155-160. Macdonald, D. 2001. Shrews. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. Andromeda Oxford, Oxfordshire, United Kingdom. Ryan, J. M. 1986. Dietary overlap in sympatric population of Pygmy Shrews, Sorex hoyi, and Masked Shrews, Sorex cinereus, in Michigan. Canadian Field-Naturalist 100(2): 225-228. Wund, M. 1999 Dec. Sorex hoyi. <http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/sorex/s._hoyi$narrative.html> Accessed 2 Nov 2003. Reference written by Kyle Cutting, Biol 378: Edited by Chris Yahnke. Page last updated