Sorex palustris The Northern Water Shrew

advertisement

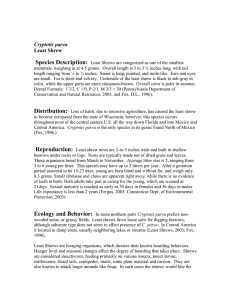

Luke Lenard Sorex palustris The Northern Water Shrew The hardy water shrew is active day and night and can swim under the ice. © Moose Peterson Description Sorex palustris belongs to the Order Insectivora, Family Soricidae, and the Subfamily Soricinae. It is of the genus Sorex, and the subgenus Otisorex. 9 or 10 subspecies of Sorex palustris are extant, and include; Sorex palustris albibarbis, S.p.brooksi, S.p. hydrobadistes, S.p. gloveralleni, S.p. navigator, S.p. labradorensis, S.p. palustris, S.p. punctulatus, and S.p. turneri. (Beneski Jr. and Stinson 1987) The water shrew is a large shrew, adults range from about 130-170mm in total length. Tail lengths range from 55-90mm in adults. Males typically are larger than females, especially sexually active males. They show significantly longer total lengths and total body masses. Fur is darker dorsally than ventrally as in most shrews. Typically the dorsal fur is black or dark grey, and the ventral pelage is white, with the chin region being the lightest color on the body. They also have stiff hairs called fibrillae on their feet, which provide added thrust for swimming during dives (Beneski Jr. and Stinson 1987). Sorex palustris has the dental formula i 3/1, c 1/1, p 3/1, m 3/3 = 32. Compared to other shrews, S. palustris has a relatively large skull. The upper jaw has 10 unicuspid teeth (5/side), with the fourth being larger than the third. The zygomatic arch is absent in all shrew species. Distribution in Wisconsin The distribution of the water shrew has been debated and studied for years. The northern limit of the range in particular is not very well known, as specimens turn up from regions further north than previously suspected. In general, the shrew thrives in cool areas of North America, including Canada, parts of Alaska, and cool regions of the U.S. It has been found as far north as the Yukon Territory. (Jarrell 1986) The water shrew is abundant in the northern two-thirds of Wisconsin, but rare in the southern third. Specimens have been found in Douglas, Vilas, and Marinette counties, and 4 more were found in the vicinity of Rhinelander, Oneida county (Cory, 1912). They are confined to the northern part of the state, mostly in the Canadian life zone and upper Transition zone, south in the central part of their range to northern Clark county (Jackson 1961). The black dots on the map represent areas where a specimen of Sorex palustris was previously collected. Ontogeny and Reproduction Sorex palustis' maximum life span is about 18 months. Water shrews mature earlier than most other species of shrews, but most females don't reproduce until after their first full winter. Ovulation is induced by copulation, and most ovarian activity takes place starting in January, and ends in August. A typical female will have three litters per year, with an average of 6 young per litter. The gestation period is not known, but for most shrews it is about 21 days (van Zyll de Jong, 1983). Ecology Water shrews, are usually found near water, hence the name. Most commonly, they are near water with a high number of invertebrate prey. This includes streams and small rivers, springs, or sometimes near lakes or ponds. They often travel on small runways near stream banks. Predators of the water shrew include many species of hawks, fish, and owls, as well as mink and weasels. Water shrews are insectivorous. A large portion of their diet is slugs and earthworms, and in many cases, aquatic invertebrates, but they are also known to eat terrestrial invertebrates such as grasshoppers and crickets. (National Geographic Society 1981) A small percentage of their diet may be small or young fish, fish eggs, leeches, small crustaceans, and even plantlife. (Dunstone and Gorman 1998) Behavior Water shrews can dive into water or run across the surface. They have been seen running as much as five feet across the waters surface. They dive into the water to escape predators or catch their prey, and they continue to use the water in this manner throughout winter. They walk across the surface by using air bubbles trapped in the fibrillae of their hind feet (Grosvenor 1979). Sorex palustris often feeds in the substrate, but its dive time is limited because the shrew is covered in a layer of air which causes it to float if it stops paddling. If prey is abundant, water shrews will often cache their food in logs or crevaces for later consumption. They kill larger prey items by biting them in the head, and often use their forefeet to hold the prey down while tearing off pieces to eat. Remarks The water shrew needs to be studied in more detail in Wisconsin. There is a drastic lack of material on water shrews in Wisconsin, but a plethora of material from Canada and Alaska especially, and also a number of articles from western states such as Montana, Utah, and Wyoming. There are also more articles from the east coast states such as Virginia and Maine. Our general area near the great lakes also has a lot of articles on the water shrew, but most are from Michigan and Minnesota. According to the Wisconsin department of natural resources the water shrew is not threatened or endangered, but is one of the many animals that are of special concern. If their habitat isn’t preserved, and the environment continues to degrade, the water shrew will soon be on the threatened or endangered species list as well. (WDNR, 2003) Literature Cited Beneski Jr., John T. and Stinson, Derek W. 1987. Sorex palustris. The American Society of Mammologists. Burt, William H. 1977. Mammals of the Great Lakes Region. The University of Michigan Press. Cory, Charles B. 1912. The Mammals of Illinois and Wisconsin vol. 11. Field museum of Natural history zoological series. DNR, Wisconsin. 2003. http://www.dnr.state.wi.us/org/gmu/upsis/imp/appendix%203.pdf Dunn, Ann Bailey. 2003. http://www.wnrmag.com/stories/2003/oct03/shrew.htm Dunstone, Nigel and Gorman, Martyn. 1998. Behavior and Ecology of Riparian Mammals. The Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge. Grosvenor, Gilbert M. 1979. Wild Animals of North America. National Geographic Society. Jackson, Hartley H. T. 1961. Mammals of Wisconsin. The University of Wisconsin Press. Jarrell, Gordon H. 1986. A Northern Record of the Water Shrew, Sorex palustris, from the Klondike River, Yukon Territory. Canadian Field-Naturalist 100(3): 391. National Geographic Society. 1981. Book of Mammals vol. 2. Special Publications Division of the National Geographic Society. Wojcik, Jan M. 1998. Evolution of Shrews. Mammal Research Institute, Polish Academy of Sciences. Reference written by Luke Lenard, Biol 378: Edited by Chris Yahnke. Page last updated