OLDER ADULTS & HIGHER EDUCATION

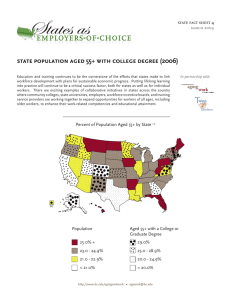

advertisement