GLOBAL NAU Global Education: A Path to Scholarship and Restored Hearing

advertisement

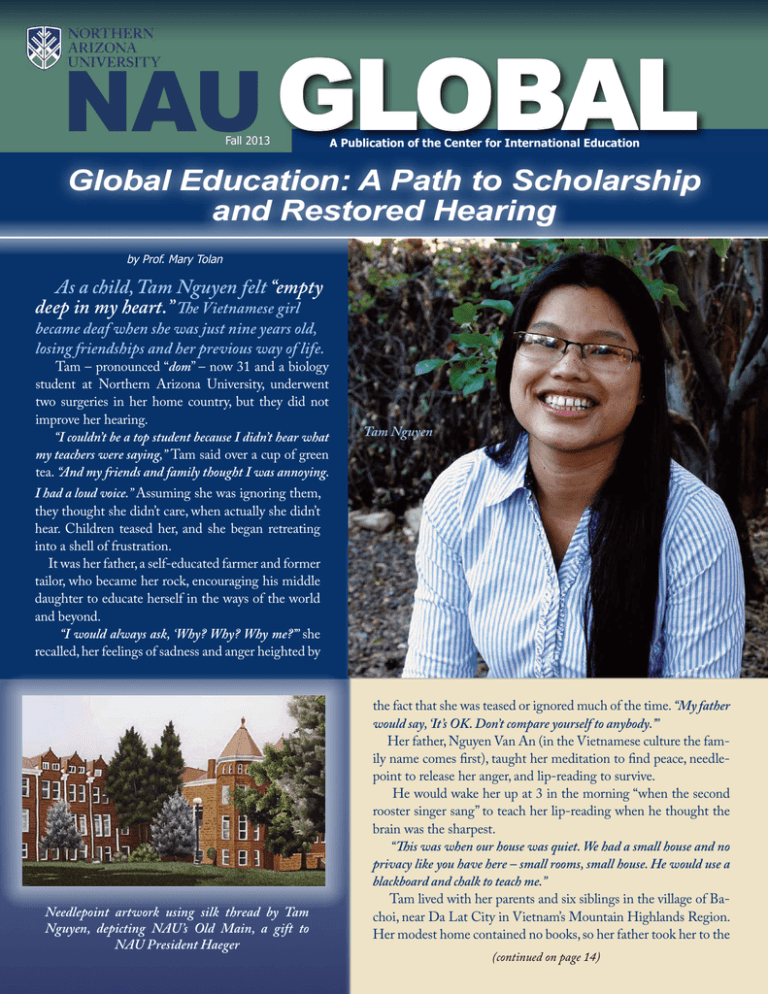

NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 A Publication of the Center for International Education Global Education: A Path to Scholarship and Restored Hearing by Prof. Mary Tolan As a child, Tam Nguyen felt “empty deep in my heart.” The Vietnamese girl became deaf when she was just nine years old, losing friendships and her previous way of life. Tam – pronounced “dom” – now 31 and a biology student at Northern Arizona University, underwent two surgeries in her home country, but they did not improve her hearing. “I couldn’t be a top student because I didn’t hear what my teachers were saying,” Tam said over a cup of green tea. “And my friends and family thought I was annoying. Tam Nguyen I had a loud voice.” Assuming she was ignoring them, they thought she didn’t care, when actually she didn’t hear. Children teased her, and she began retreating into a shell of frustration. It was her father, a self-educated farmer and former tailor, who became her rock, encouraging his middle daughter to educate herself in the ways of the world and beyond. “I would always ask, ‘Why? Why? Why me?’” she recalled, her feelings of sadness and anger heighted by Needlepoint artwork using silk thread by Tam Nguyen, depicting NAU’s Old Main, a gift to NAU President Haeger the fact that she was teased or ignored much of the time. “My father would say, ‘It’s OK. Don’t compare yourself to anybody.’” Her father, Nguyen Van An (in the Vietnamese culture the family name comes first), taught her meditation to find peace, needlepoint to release her anger, and lip-reading to survive. He would wake her up at 3 in the morning “when the second rooster singer sang” to teach her lip-reading when he thought the brain was the sharpest. “This was when our house was quiet. We had a small house and no privacy like you have here – small rooms, small house. He would use a blackboard and chalk to teach me.” Tam lived with her parents and six siblings in the village of Bachoi, near Da Lat City in Vietnam’s Mountain Highlands Region. Her modest home contained no books, so her father took her to the (continued on page 14) FROM THE VICE-PROVOST Just a few days ago, I learned about the fascinating story of how the European Union (EU) came to consider and ultimately endorse ERASMUS, the highly successful project that facilitates the mobility of European students within the European Union. A group of individuals who came up with the idea for the general ERASMUS framework decided to go to the EU to present the concept. They were given a hearing but then told that it would be too expensive to fund, too difficult to organize, as each country already had its own system, etc., etc. They went away a bit discouraged but decided to look at the agenda for that very day at the EU. They discovered that just before they presented, there was a debate about how the stockpile of stale butter that builds up within the EU each year would be discarded. They further learned that the EU agreed to pay the bill, which was more than 10 times what it would have cost to implement the ERASMUS program. In effect, the EU was willing to pay millions of dollars to get rid of stale butter but unwilling to pay substantially less to support the international education NAU GLOBAL Harvey Charles, Ph.D., Editor Emma Holmes, Assistant Editor NAU Global features the work of faculty to internationalize the curriculum and the campus; it is published twice yearly by the Center for International Education Northern Arizona University PO Box 5598 Flagstaff, AZ 86011 e-mail: cie@nau.edu web: http://international.nau.edu/ Tel: 928-523-2409 Fax: 928-523-9489 2 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 Competing With Stale Butter By Dr. Harvey Charles of its students, a project crucial for its own economic and political future. When the discrepancy in values was pointed out, the decision was made to fund ERASMUS. the EU was willing to pay millions of dollars to get rid of stale butter but unwilling to pay substantially less to support the international education of its students ERASMUS has enjoyed an amazing success story since its founding in 1987. More than 3 million students have had the chance to study abroad since then, and more than 300,000 faculty and staff of EU universities have been able to participate in exchanges (http://ec.europa.eu/ education/lifelong-learning-proThis gramme/erasmus_en.htm).1 is remarkable by any measure, and has been aptly characterized as the world’s largest and most successful student-exchange program. Because of ERASMUS, students are having rich immersive cross-cultural experiences as well as learning new skills through internships. Faculty are collaborating with their colleagues at universities across the EU, and as a consequence, pushing the boundaries of knowledge and transferring that knowledge in their classrooms. It is clear that the Europeans are doing this not only because they can afford it, but because they see this as fun- damental to the integration project, which, by extension, is the only real hope they have of avoiding a regression into the internecine warfare that has shaped so much of European history. With a strong higher-education infrastructure, with citizens who are well educated to meet the demands of a globalized world, and with their ability to respond to the need for intellectual capital, the Europeans are better positioned to build a future of peace and prosperity. Is there a counterpart to the ERASMUS program in the United States? Well, the only one that exists at a national level is the Benjamin A. Gilman Scholarship, which is sponsored by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State and managed by the Institute of International Education. Granted, there are other programs that fund students to study abroad, like the Truman fellowship and the Marshall scholarship, but these are elite programs that fund very few students per year. The Gilman scholarship is more democratic in its application and “offers grants for U.S. citizen undergraduate students of limited financial means to pursue academic studies or credit-bearing, careeroriented internships abroad” (http:// www.iie.org/en/Programs/GilmanS c h ola r s h i p -Progr a m/ A b o u t the-Program).2 This relatively new scholarship opportunity funds about 2,300 students per year at an average scholarship amount of $4,000. Unlike ERASMUS, it does not have (continued on page 15) Global Perspectives and Interdisciplinary Research: Two Necessary Approaches to Understanding By Prof. Scott Anderson Our Future What comes into your mind when you hear the word “ecolog y”? If in your mind’s eye you see communities of plants or animals, fields or forests, lakes or oceans, you would be in good company. Now, what comes into your mind when you hear the word, “geology”? Do you think of rocks, sediments, fossils, periods of time long since above: coring the Laguna de Mosca in Spain past? How about a time when climate was different than today? Again, you would be correct. Ecology and geology - two separate fields of knowledge in the sciences. Or are they that different? Can they be complementary? One field of science combines these two fields in the interdisciplinary study of “paleo-ecology.” Paleoecology is then the study of biological communities as they have occurred in the past, and their relationship with the environment that existed at that time. Here at NAU we have a thriving program in paleoecology, which can be not only a portal to a study of the past, but also a means to (continued on page 18) (continued on page 16) NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 3 Sprechen Sie STEM? From left to right: David James, Univ. of Pennsylvania; Marianne Lancaster, Emory Univ.; Katja Fullard, Goethe Institute; Tobias Barske, Univ. of Wisconsin Stevens Point; Ninja Nagel, Barrington High School; Damon Rarick, Univ. Rhode Island; Gisela Hoecherl-Alden, Boston University Taking a Closer Look at Foreign-Language Instruction for Science, Math, and Engineering Majors By Prof. Eck Doerry Ask an average person on the street what they think of first in relation to science and engineering and they are likely to say “data . . . lots of data.” Although collecting data is certainly an important element of research and innovation in the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) disciplines, new insights in these areas actually arise not from the data per se but from the critical analytic discussion about that data within the scientific community. Communicating face to face in labs or at conferences, writing in e-mails and scientific communications or via videoconference in online meetings, scientists collaboratively test, compare, and discuss their findings to arrive at new insights about what the 4 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 data actually tell us . . . about climate change, or the strength of a new material, or the efficacy of a new production method. Clearly, efficient, concise technical communication is the lifeblood of the science and engineering enterprise. One side effect of the rapidly globalizing economy has been that communication among scientists and engineers has become more challenging, as research and production teams and facilities are distributed across many cultures and languages in countries around the globe. Modern scientists working in globally distributed teams must find a common language, and even when that language is English, must have a keen understanding of the difficulties of communicating in a foreign language for the sake of non-native English speakers in their working groups. As a result, foreign-language training has become a valuable investment for engineers and scientists looking for leadership positions in global enterprises. The increase in engineering and science students incorporating foreign-language learning into their studies has raised an interesting question: What changes are needed in modern-language pedagogy to accommodate engineering and science majors? Most obviously, the content of language instruction materials must be adapted and extended to cover the special practical needs of engineers and scientists: vocabulary must strongly emphasize numbers, calculation, technical equipment, and scientific processes; the scenarios presented in learning exercises must focus less on cafés and marketplaces and more on factories, labs, and the technical processes that happen in them. A somewhat less obvious in(continued on page 19) Teaching Sustainable Humanities in a Global Age below: a scene from Ambrogio Lorenzetti’s “Allegory of Good Government.” By Prof. Paul Keim By By Prof. Gioia Woods After 12-year-old Cosimo Piovasco di Rondò got in trouble for refusing the snails his sister Battista prepared for dinner, he below: CCS 250 (“Landscape, Literature, Sustainability”) students investigating representations of the pastoral in Buontalenti’s grotto, Boboli gardens, Florence, Italy. NAU students included here are Devereux Fortuna (at far left) and Kali Bills (second from right). climbed up the holm oak outside the dining room window and swore never to come down again. He kept his word, and during his long life in the trees, Italo Calvino writes, Cosimo searched “for a more intimate link, a relationship that would bind him to each leaf and chip and tuft and twig.” The 1957 work Baron in the Trees, Italian novelist Calvino tells us, is a conte philosophique—a satirical exploration of contemporary issues. For Calvino, midcentury Italy—indeed, all of Europe and much of the Western world—was suffering from an environmental crisis that moved beyond silent springs, proliferation of nukes, and unchecked urban development. The crisis was existential, and had to do with the difficulty humans had in making a connection with the natural world. Calvino’s utopian novel plays with the idea of reinhabitation and its results. Cosimo’s many decades as an arboreal baron force a radical change in perspective, not only about the natural world but about gendered expectations, labor and class, and property and free will. Calvino provides the reader an opportunity to consider (continued on page 16) (continued on page 17) Fall 2013 NAU GLOBAL 5 Cuisine in the Ming Dynasty: A Window into Culture with easy access to the trade routes used for hundreds of years, the city of Beijing’s geographic position brought to it a rich assemblage of food plants, spices, and flavorings from a variety of cultures. lations on dining protocols, with a special emphasis on the classifications of dining vessels and their usage. The privilege of rank was a primary consideration when deciding eligibility to access a certain vessel. For example, dukes, marquises, and officials of the first and second ranks were entitled to use golden wine bottles and wine cups, while the rest of the emperor’s court was restricted to the use of utensils made of silver. During the Ming Chenghua reign, it became quite trendy to pursue material comforts, and the imperial palace played a leading role in this endeavor. Although tofu remained an essential offering on the royal menu, its courtly version was made not from bean curd from yellow beans, but rather from the brains of nearly a thousand birds, dressed to resemble the lowly tofu dish. As an example, the pastoral peoples the city faced in the north, particularly the Mongols—who were to become China’s rulers in the 14th century—made substantial contributions to the culinary culture. Following the Yuan conquest, the middleAsia collaborators, whose population penetrated throughout northern China, brought significant Islamic influences to regional cuisines. And if Marco Polo’s travelogue account is to be believed, there was a sizable population of “Christians, Saracens, and Cathayans, about 5000 astrologers and soothsayers” among the “Khanbalik” or Beijing inhabitants at the time of his wanderings. The conglomeration of foreign and domestic cultures would inevitably bestow upon the metropolis a vibrant and comprehensive culinary legacy. The Ming founding emperor Hongwu was a man of austerity and The Hongzhi emperor ordered all the shops and inns abutting the avenues in Beijing and Nanjing to have their lanterns lit in the evening, illuminating the streets as his ministers returned home from royal banquets. The writings of later Ming scholar-officials were filled with records of parties, menus, and cooking styles. Indeed, Epicureanism had become such a popular topic that one’s knowledge of cuisine was reckoned a sign of erudition and nobility. Zhang Juzheng, the prime minister of the youngster Emperor Wanli, complained that he had “nowhere to settle chopsticks” when more than 100 dishes were laid in front of him at a regular family dinner. Regarding food today — considered one of the four “primary material concerns” besides clothing, travel, and housing: it is essential By Prof. Xiaoyi Liu Perched at the northeast corner of the China domain, frugality. To prevent his descendants from indulging in gastronomic excess, he strove to set up an exemplary dining pattern. He demanded that palace foods be prepared in “regular supply,” a family-style cuisine. And to show that he had not forgotten his simple origins, he made tofu a requirement for his breakfast and dinner menus. Empress Ma frequently visited the palace kitchen to supervise the cooking. But for Hongwu, dining was more than an occasion to display the virtue of frugality. It constituted an important institution in which distinctions regarding social hierarchies were to be addressed. He devised a set of regu- (continued on page 17 ) 6 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 Just Food: F Exploring the Intricate icate Web of Sustainability, Citizenship, and Global Learning By Prof. Kimberly Curtis “Democracies do not sustain themselves; they must be nurtured by engaged, knowledgeable citizens. Engaged, knowledgeable citizens are not born; they are developed through citizenship education.” — Robert Leming, Center for Civic Education As we approach San Luis, Arizona, at 4 a.m., sky pitch black, we can see a string of lights stretching miles and miles to our left and to our right. Although we know we are headed to the border, it takes a while for it to sink in: this is “the wall.” Once in San Luis, we dis- embark from the vans. It is like a smalltown version of Times Square in the middle of the night. In the streets, people are streaming north. Women stand in small groups, their faces wrapped in bandanas, hats, gloves — bodies covered head to toe. There are people of all ages, from young teenagers to very old men. Nearly all have been up on the Mexican side of the border since 1 a.m., waiting in line to cross so they can work in the vast industrial agricultural fields of Yuma, Arizona. Our first-year seminar class, “Just Food,” has come to San Luis in the wee hours to bear witness, to learn, and to talk to these mostly Mexican workers. Students are nervous. We all are. We’ve divided into small groups, each with someone who can translate. We ask and we listen, gathering stories until, as the light breaks, the last of Yuma lettuce harvest operation the thousands of workers who cross each day have boarded buses that will take them to the fields. It is late March, the end of the winter growing season in Yuma, where 90 percent of the winter greens consumed in the United States are grown. Who knew? And who knew about the lives of those who harvest and process this bounty? Why must The course “Just Food” asks a not-so-simple question: What might a just food system look like? Few students have given this question much thought they be up at 1 a.m., returning home after recrossing at 6 or 7 in the evening? How can they raise their families? Go to a doctor? Get their hair cut? Do they have adequate protection from pesticide exposure? From sexual harassment or retaliatory firing? Are they fairly compensated for their back-breaking labor? Why do they do this? On our three-day field trip to San Luis and Yuma, students pressed for answers to these and many other questions, as they spoke to migrant workers, the farmers who employ them, technical experts who gain their livelihood in industrial agriculture, human rights advocates, and border patrol agents. The course “Just Food” asks a notso-simple question: What might a just food system look like? Few students have given this question much thought; most know next to nothing about where their food comes from, who labors to get it to their tables and under what conditions, or how the current system affects the earth. In the classroom, they study the industrial food system with special attention to justice for workers, for animals, for the health of the soil, water, and the earth’s climate. Without exception, the field experience transforms their learning. A political theorist by training, I recognize what transpired on the field trip as a powerful instance of citizenship edu(continued on page 16) NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 7 Transforming Excellent Graduate Students into Repository of World-Class Professionals Religious Objects: By Prof. Fredricka Stoller four Fulbrighters currently enrolled in NAU’s MA TESL program from Yemen, South Africa, Krygystan, and Uzbekistan The Fulbright Foreign Student Program (http://foreign.fulbrightonline.org), one of the U.S. government’s premier educational-exchange efforts, brings international students to the U.S. for graduate-level study. In fact, more than 1,800 new Fulbright Fellows enter U.S. academic programs each year. The highly competitive awards are offered to the best and brightest, typically early-career professionals who, upon completion of their studies, return to their home countries to take on leadership positions, often in universities or government service. Recipients of this prestigious award receive grants that cover all expenses, including travel, tuition, room, board, and educational materials. To be awarded a fellowship, prospective students apply through either the Fulbright Commission or the U.S. Embassy in their home countries. NAU has hosted international “Fulbrighters” across campus in numerous graduate programs. NAU’s Master of Arts in Teaching of English as a Second Language (MATESL) and PhD in Applied Linguistics programs, housed in the English Department, have attracted many Fulbright Fellows in the last two decades because of the international reputation of the programs and faculty. We have hosted dozens of 8 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 fellows from countries as diverse as Afghanistan, Albania, Brazil, Colombia, Costa Rica, Egypt, Gabon, Indonesia, Japan, Korea, Kyrgyzstan, Mali, Mexico, Niger, Oman, Pakistan, Panama, Russia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Swaziland, Thailand, Turkey, Uzbekistan, Vietnam, and Yemen. At NAU, these students enrich our programs and campus community in many ways. In class, they offer new insights in classroom discussions and broaden the worldview of our domestic students. Moreover, their presence on campus promotes mutual understanding between domestic students and those from other countries. The Fulbrighters themselves gain a tremendous amount from their NAU experiences, including introductions to and involvement in new types of classroom environments, what they perceive as novel faculty-student relationships, and current thinking in their fields of study. MA-TESL Fulbrighters often share their perspectives at local, state, and national conferences, contributing to the professional growth of other language researchers and teachers. After the first of their two years at NAU, currently enrolled MA-TESL Fulbrighters—from Kyrgyzstan, South Africa, Uzbekistan, and Yemen—have all described their MA-TESL experiences as “life changing.” Their experiences have altered the ways in which they think, view the world, and perceive the field of applied linguistics and language teaching, and they see themselves as “cultural ambassadors” (who can and do break down the barriers of stereotypes) and professionals who can make a difference when they return to their home countries. Their comments capture the value of their Fulbright experiences at NAU: - “My Fulbright experience at NAU is, no exaggeration, the most productive and rewarding experience in my life. NAU has a top-notch TESL program. The inten(continued on page 17) Museums as Sites for Global Learning By Prof. Bruce M. Sullivan photo © Bruce M. Sullivan As I walked again through the Buddhist sculpture gallery at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, approaching the 18th-century gilded copper statue of the Buddha seated in meditation, I was surprised to see a museum patron seated next to the statue, emulating the posture of the Buddha. He left before I could ask about his motivation for performing what seemed an act of reverence, perhaps even worship, in a space usually deemed more suitable to meditation of aesthetic, rather than religious, intent. His presence raises questions about the purposes for which museums exist, and the experiences of patrons in visiting them. For a recent research project, I have visited museums throughout the United States and the United Kingdom, exploring how museums represent Asian religious traditions through the exhibition of objects of religious significance. Hinduism and Buddhism are very much minority religions in the Western world, and the collection by museums of Asian religious artifacts is an international enterprise. The image of the seated Buddha in a museum in London is a striking example of the global movement of objects. Created about 1750 for installation in a Buddhist temple, the statue was commissioned by a Tibetan Buddhist monk, Rol pa’i rdo rje, friend and religious teacher of Qianlong, the Emperor of China, as its inscription in Tibetan reveals. Acquired by the Indian Parsi industrialist Sir Ratan Tata, it was donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1920 by his wife. So a Tibetan Buddhist statue from Imperial China, acquired by an Indian of Persian heritage, can now be viewed in England in the Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Gallery for Buddhist Sculpture! The foundation’s educational mission is to foster “appreciation of Chinese cultural heritage and the application of Buddhist insights in today’s world . . . [and] to further Buddhist scholarship and enhance its global impact” (http://www.rhfamilyfoundation.org/). Another example of global learning through museum exhibitions that I have found fascinating is the St. Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art, in Glasgow, Scotland. Here, the world’s major religions are represented through exhibited objects, juxtaposed in sometimes startling ways. Opened 20 years ago, the museum has the explicit mission “to promote understanding and respect between people of different faiths and of none, and offers something for everyone” (http://www.glasgowlife. org.uk/museums/st-mungos/About/ Pages/default.aspx). Just a month after the museum opened, its mission of promoting tolerance was tested by a fanatic, who threw the bronze statue of Śiva to the ground, damaging it while also demonstrating the need for the museum and its educational mission. Built next to and in the style of Glasgow’s Catholic cathedral, in mostly Protestant Scotland, the museum also features a “café, which opens out into the first Zen garden in Britain.” Its exhibitions are explicitly comparative, inviting visitors to apprehend religious traditions’ similarities and differences. Museum collections are vast, and there are many kinds of museums. Some include in their collections objects that were previously in worship contexts (temples, monasteries, etc.). Are such objects to be regarded as still religiously significant or as formerly religious but now art objects, or do they occupy a category all their own, simultaneously of religious, cultural, and aesthetic importance? Visitors may have different attitudes toward and experiences of the objects in museums: what for one visitor is an art object can be a religiously significant symbol for another. And for some, an object may convey both artistic and religious resonance. Art museums (continued on page 18) NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 9 By Prof. Fred Summerfelt the author dwarfed by a telescope at Mauna Kea, Hawai’i If you’ll pardon the pun, astronomy is a universal human interest. The basis of today’s astronomical systems began in ancient Greece, and just about every native culture around the world has astronomy mythology as part of its origin story. Modern astronomy is also universal. My collaborators and our observatories are all over the world, and our conferences are truly international. Astronomy is a great way to see the world, and I have traveled, in the name of work, to Europe, South America, Asia, Oceania, and Africa. Cultural difference is encountered not only on trips abroad; even in this country, astronomy travel frequently involves visiting land that is treasured by Native Americans. Being an astronomer who is aware of cultural diversity means more than just wearing Hawai`ian shirts to work. How should I be an astronomer in this global field? As with any other foreign travel, be patient and humble. Astronomers and technical staff around the world have learned to speak my language, and are sharing their technical and natural resources with me. I don’t speak much Spanish — hello, goodbye, please, thank you, and a bunch of food words — but it Astronomy as Perspective on the Universe and Our World By Prof. David Trilling is a good start in connecting with and showing gratitude to my local hosts. Be interested. Talk to the locals. When I go to Hawai`i for work, I don’t stay in the resorts on the beaches; instead, I room in the rather lower-rent astronomer dorms, shop where the locals shop, and find out from the locals where the best beaches are. Be thankful and respectful. I am fortunate to visit many places that welcome astronomers — sometimes even to holy mountains where observatories are now located — and we should acknowledge people sharing their places with our facilities. Many astronomers now include a phrase in Hawai`ian in the acknowledgments sections of papers that use data collected in Hawai`i. The core of all our work is physics, of course, which contains more universal truths. The equations are the same everywhere. Optics works regardless of what language you trained in. It always feels like a great success to travel halfway around the world, navigate unfamiliar transportation and logistical issues, and end up at a telescope on some remote mountaintop. This is our common ground, where I interact with local astronomers and staff and with astronomers visiting from elsewhere in the world. We take great pleasure in our arcane technical discussions. After all the travel and language issues, at the bottom we share a fascination with the universe and a thirst to understand our origins. This is truly a common interest. What is the importance of teaching NAU students how to work in this global intellectual community? This generation of students will only know instantaneous communication with people around the world. On the one hand, this gives our students an opportunity to talk to and work with people from around the world with essentially no barriers. The world is their oyster. On the other hand, e-mail and social media can mask differences: We assume that the person on the other end of the communication has the same cultural background, leading perhaps to misunderstandings and confusions and worse. The human element is critical. We must encourage our students to meet people from other backgrounds face to face, to create relationships and deal with people directly. (continued on page 18) Educators Push for School Access for the World’s Children By Prof. Rosemary Papa Meeting in San Francisco in collaboration with the American Educational Research Association on May 1, 2013, a group of eighteen prominent national and international scholars met in San Francisco and recommitted themselves to confront issues of poverty faced by schoolchildren in the world and to work towards global improvement in the education of girls. These urgent matters are a worldwide problem with over 100 million children not in school, the majority being girls. The two primary thrusts surrounding how to enable Flagstaff Seminar research to activism was seen as a clear call to action for the participants to continue their work towards ensuring that education is a basic human right and that educational leaders can and must become emboldened to seek solutions that go beyond the school house door, even if this means confronting historic cultural and political forces that act as barriers to basic improvements in the reach and quality of education in the world. Reaction to the concept paper framed the discussion, that is, how do we extend what we do beyond leader preparation? Points of discussion included the following: 1. A document of intentional work—A call to action and activism 2. Three issues-access, quality, and equity- all must be addressed 3. Education, all in education, must tackle all together 4. Shortage of teachers-what values are held-have a smaller focus-what could be a narrower focus? Quality of pre-service training and in-service is critical. 5. Holistic language in education-what’s missing becomes the notion of the purpose of education; going beyond schools; so tied to comprehensive reform that the beauty gets co-opted by language used by educational researchers. 6. Food scarcity exists for 25% of children in the world: they go to bed hungry. What does this mean just to the US? And, to the education system that really teaches the whole child? What is the role of the school in that community? How do we promote sustainable development? 7. Leaders in schools want to know how to do Educational Sustainability Develoment. Leaders without borders know what is happening elsewhere. They must know the How but also the moral Why. 8. How do we extend what we do beyond leader preparation and focus on Purpose, not just the How? 9. There are lots of borders, not just geographical. Our responsibility is to prepare educational leaders. Standing left to right: Carol Mullen Virginia Tech University; Martha McCarthy Loyola Marymount Los Angeles; Jim Berry, Eastern Michigan University; Nathan Bond, Texas State University; Uche Grace Emetarom, Nigerian Professors of Education Administration; Faye Snodgress, Executive Director of Kappa Delta Pi International Honor Society in Education; Carolyn Shields, Wayne State University; Ira Bogotch, Florida Atlantic University; Michael Sampson, Northern Arizona University; Concha Delgado Gaitan, University of California-Davis; Jane Lindle Clemson, University of South Carolina; Lisa Ehrich, Queensland University of Technology, Australia; and Don Scott University of Calgary, Canada. Seated: Fenwick English, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill; Rosemary Papa, Northern Arizona University Discussions and commitments focused on the compelling needs of education worldwide: the de-profes- sionalization of the teaching profession, the increasing poverty gap between the have’s and have not’s, and the political world issues that address political issues: resource allocation, partnerships with organizations to leverage political clout, global marketization and how not to feed the beast, access to technology and the generation of knowledge, and how we organize to address the policies that we do not have much leverage over. We concluded this meeting with the following actions: 1. Continuing to develop the networking with individual scholars and professional organizations worldwide 2. Continue to identify the issues 3. Identify the opportunities for action 4. Identify the efforts to work for locally based solutions The collective research and scholarship of the group spans four decades of national and international work and exceeds 100 books, handbooks and encyclopedias, as well as hundreds of research journal articles in most major North American, European, Australian and African nations. The FS scholars have set the next meeting for August 2-3, 2015 in collaboration with the National Council of Professors of Educational Administration. For additional information, visit www.flagstaffseminar.com or www.educationalleaderswithoutborders.com Fall 2013 NAU GLOBAL 13 (continuation of articles) Scholarship and Restored Hearing (continued from page 1) library and encouraged her to read. He took her out into nature and the family farm to teach her to observe and meditate. While her mother, Le Thi Sen, wanted to protect her deaf daughter, her father always pushed her out into the world and encouraged her to pursue education, including the study of English. In fact, he found people to introduce her as a child to English, Chinese, German and French. Because of her society’s belief in karma, Tam was burdened with deep questions about her hearing loss, the result of an infection. “If you have good karma, you have a good kid,” she said. “So how can you have good karma if you have a child with a disability?” Tam’s karma was never bad, of course, and finally led her to Flagstaff and NAU. After finishing high school in Vietnam, Tam went on to earn a medical-assistant diploma from Lotus University in Ho Chi Minh City, formerly Saigon, and traveled throughout her country for two years. Her father encouraged her travel, knowing that while she could not hear, she could observe people and nature and life to educate herself. She continued improving her silk needlework, becoming a skilled embroidery designer and artist. In 2007, Tam crossed paths with an American who was visiting Vietnam. She met him through her sister, who asked Tam to show him around the country. After he left, they stayed in touch. It wasn’t long before he asked her to visit him in Flagstaff. With the blessings of her parents, she traveled to Flagstaff 14 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 “Inner Peace,” Tam Nguyen Much of her delicate, realistic embroidery is of birds (which represent freedom to Tam) and of flowers. photo: David Edwards where her sister already lived. Later that year, she married Sam Neeley, and they live in Flagstaff. In Phoenix, Tam found a specialist and after three operations, her hearing was restored. Because she had been deaf for two decades, she needed to improve her speech. She wanted to be heard and understood. She spent three years in NAU’s Speech Therapy program to learn how to articulate English words better. Now she is working on a biomedical degree at NAU, and has participated in research in the Biology Department as an undergraduate. She balances her schoolwork with her needlework. Much of her delicate, realistic embroidery is of birds, which represent freedom to Tam, and of flowers. The (continuation of articles) framed artwork ranges from a family of cranes to sprays of orchids, with vivid colors shining through the silk. She began the work as a hobby, but now hopes to sell some of her art to help pay for her education. Her artistry in needlework is also reflected in a 3-D embroidered piece of NAU’s Old Main, which she presented to President John Haeger in the Fall Semester, 2013. “It is simply exquisite,” said Harvey Charles, NAU’s Vice Provost for International education. But his praise goes beyond her artistic talent. Charles marveled at Tam’s resolve. “How could a non-native speaker of English overcome all these pretty significant challenges, come to the US, have her hearing restored and still be so motivated to invest all the time and resources necessary to pursue a career in scholarship?” he wondered. For Tam, it is all about her father, and others who have helped her along her path. “He sacrificed his life for me,” she said in a soft yet strong voice. “When I was young I was not appreciating him. I would get upset with him when he would wake me at 3 in the morning. But now I see all he did for me.” And he encouraged her to travel to the United States to try to regain her hearing, and better her life. “In my country, traditionally the girl cooks, does housekeeping, manages the family and raises kids,” she said. “The woman doesn’t have a voice to talk. My parents told me, ‘There is no way to get out,’” because the family was working class. “OK, I’m starting my life,” she said of her Flagstaff life, as her voice bubbled in laughter. “I want to be a researcher.” Tam Nguyen is a client of Literacy Volunteers of Coconino, and has published several articles in the Arizona Daily Sun “Gardening Etcetera” column, edited by Dana Prom Smith, one of Tam’s Literacy tutors. Her most recent column focused on the vegetable daikon, and her mother’s cooking of this leafy plant with its white root. She has a deep knowledge of plants and food production. “I can never say enough thanks to the people who have helped me,” she said of Smith and of Ann Beck, former executive director of Literacy Volunteers. “Ann is second mother to me.” Beck called her young friend a phenom. “Tam’s enthusiasm for life and learning is infectious. She makes friends everywhere and learns from everyone she meets,” Beck said. Tam received an International Office scholarship to pursue research with biology professor Sylvester Allred, focusing on the traditional and commercial impact of foods. “The knowledge he knew, I carry with me,” she said of her father. “His life, his secrets. My father said, ‘Education does not make your stomach full. But it will make things different.’” Mary Tolan is Associate Professor in the School of Communication needlepoint by Tam Nguyen Stale Butter (continued from page 2) an exchange component, but this scholarship has made a profound difference in the lives of many of these students. They return preaching the study-abroad mantra, which is, “study abroad has changed my life!” What is astounding, however, is that while the EU spends more than $600 million per year on ERASMUS, the U.S. government spends barely more than $9 million on the Gilman program. This is happening at the same time as there is, in the U.S., an obsessive focus on MOOCs and three-year bachelor’s degrees, and while we witness the largest decline in state and federal funding of higher education in U.S. history. So we are now able to save millions of tax dollars -- big deal! But what are we losing as a consequence? What could we possibly be thinking, a question that historian Timothy Garton Ash recently chose to ask in his own way, in a piece in The Guardian in which he recommends that “America should do a reverse Columbus.”3 He argues that the world has long lost reason to discover America, given our penchant for inflicting self-harm (the shutdown of the U.S. government being only the most recent example), and the consequent erosion of political power and prestige. Rather, he believes, Americans need to discover the view of America by the rest of the world. I think that Ash is on to something, but I would extend his belief a bit further. It’s not good enough for Americans to only discover how the rest of the world sees them. In fact, it is much more important for Americans to learn about the rest of the world, and in doing so, they will also learn about how they are perceived by the rest of the world. And it is in this photo: David Edwards latter pursuit that providing opportunities for students to travel and live in places far away from home, as the Europeans do through the ERASMUS program, becomes critical. Not only do they learn about their host countries, but they learn about themselves in ways that might otherwise be difficult, if not impossible. If the federal government is unwilling to support a program comparable to ERASMUS and if the state of Arizona is unable to do the same, maybe it is up to individual institutions, like NAU, to ensure that all of our students get a chance to learn about the historian Timothy Garton Ash recommends that “America should do a reverse Columbus.” rest of the world. Through education abroad or even global learning in our classrooms, students have a chance to engage with the rest of the world, and in so doing, acquire the skills, knowledge and dispositions necessary to make our globalized world a better place in which to live. The European Commission, Education and Training, The ERASMUS Program― Studying in Europe and More 1 Benjamin A. Gilman International Scholarship 2 Ash, T. G. (Oct. 15, 2013). Americans Need to Discover How the World Sees Them. Adapted from: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/oct/15/ americans-need-discover-how-world-seesthem 3 Fall 2013 NAU GLOBAL 15 Sustainable Humanities (continued from page 5) the nature of reality and the abstractions humans use to make meaning about reality. The deforested Liguria of the author’s youth provides the inspiration for the fictional kingdom of Ombrosa: “once upon a time a monkey left Rome and skipped from tree to tree till it reached Spain without once touching the ground...Now the hillsides are so bare that it gives us a shock when we look at them, we who knew them before.” The new perspective Cosimo develops from this informs the epistemological setting, too: Cosimo made friends with peasant workers and asked “questions about seeds and manure which it had never occurred to him to do when he was on the ground”; he also plays with new ways of representing meaning by trying to “repeat the twitter of the birds which woke him in the morning.” Teaching a novel like Baron in the Trees is central to my contributions to global learning. As an ecocritic, I’m curious about how people across cultures have constructed and expressed relationships with the natural world. Because my training, teaching, and research have been focused in 20thcentury literature, I turn most often to cultural narratives to find that expression. Reading Baron in the Trees with NAU in Siena students during the spring of 2013 engendered research and discussion into Italian environmental history and the ways “nature” has been represented over millennia. From Theocritus to the rise and fall of Rome, from manorial farm ecology to the legacy of Francis of Assisi, from Mussolini’s “Battle for Grain” to the post–WWII miracolo economico, we gathered contextual clues that would help us understand why Cosimo takes to the trees in Calvino’s novel. We looked outside the literary text, too, to consider built environments. Centuries-old foun16 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 (continuation of articles) (continuation of articles) tains in and around Siena provided clues to the physical and metaphorical meaning of water; Tuscan farms allowed us to experience sustainable agricultural practices; traditional villa gardens inspired our learning about landscape design, class, and the staying power of pastoral values. Visual art, too, helped us develop environmental memory. Ambrosio Lorenzetti’s fresco The Allegory of Good Government gave us a glimpse into 14th-century Siena. Lorenzetti’s Siena, so realistically rendered, provided the grounds for cultural comparison. The relationship between nature and culture is not hidden, as it so often is in the 21st-century United States, but shown as intimate, inextricable, and labor intensive: Traders move between city and country laden with grain or driving livestock, city artisans make shoes or add on to existing buildings, peasant communities tend field and vine. The creation of a narrative—whether visual, literary, or architectural—is an exercise in making a world. The practice of engaging narratives from across cultures is powerful because it teaches students to imagine, analyze, critique, and love worlds they do not inhabit. This critical imagining is the heart of what many are calling the sustainable humanities, interdisciplinary, multitextual inquiry into the way humans make meaning and value about the natural world. And if it is true, what cultural critic Raymond Williams wrote, that “nature” is the most complex word in the language, then it behooves us as students and educators to engage that word from many languages and many cultures. We can be like Cosimo, whose encounters with “the stem of a plant, the beak of a thrush, the gill of a fish, those borders of the wild” made him more human, not less. cation, for after the field trip, the students’ questions deepen, go more to the root of things, get more structural: What does it mean to be a citizen of a militarized, fenced land? Why is labor so controlled when trade is not? What kind of immigration policy would be just? Who really has the power to make change? This last question students explore in a completely different way throughout the semester in “Just Food,” as they participate three hours each week in one of two community-based Action Research Teams, part of NAU’s CRAFTS initiative (Community Re-engagement for Arizona Families, Transitions, and Sustainability). In collaboration with Flagstaff Foodlink, an organization at the center of the local sustainable food movement, one team works in a community garden in one of Flagstaff ’s most socially and economically diverse neighborhoods, while the other works in elementary schools helping to build permaculture gardens, teaching (as they themselves learn) sustainable gardening to young children, and deepening the school’s commitment to sustainability education. Exploring alternatives to the industrial food model, students work together toward community-based transformation, gaining concrete social-change skills. For most, this is their first experience of being part of a great democratic social movement, a first taste of the great joys and challenges of democracy. Our Fulbright-sponsored TESL and Applied Linguistics graduates have, indeed, made a difference. Some have gone on to pursue doctorates and have now contributed to the field in the areas of disciplinary writing (Marwa Haroun, Egypt), secondlanguage reading (Eun Hee Jeon, Korea), and applied corpus linguistics and cross-cultural communication (Eric Friginal, Philippines). Many have taken on leadership roles in universities, language programs, and language-teacher associations. Eliana Lili (Albania), as an example, was hired in the only American university in Albania. She states that her Fulbright experience gave her the “competitive edge.” She is educating a new generation of Albanian students, who see her as a role model. Kabelo Sebolai (South Africa) is transforming the curriculum at the Central University of Technology in Bloemfontein, South Africa, with a focus on the literacy needs of historically disadvantaged black South African students. Billa Annassour (Niger) has taken on a leadership role at the American Cultural Center in Niamey, where he serves as English Language Program director. SonCa Vo (Vietnam) has codeveloped an online teachertraining program to reach English teachers in rural Vietnam. Sultan Mohammad (Pakistan) was promoted to assistant professor at Hazara University, where he serves as coordinator of the Master’s in Applied Linguistics Program and president of the Academic Staff Association. These few examples demonstrate that NAU’s Fulbrighters have built upon their educational experiences in our TESL and Applied Linguistics programs to become world-class professionals. Gioia Woods is associate professor in the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies Kimberly Curtis is interim director of the Master’s in Sustainable Communities program Just Food (continued from page 7) above: NAU “Just Food” students with interviewees Transforming Excellent Grad Students (continued from page 8) sity of the program has instilled in me a passion to rise up to the challenges of graduate study in the U.S. and be a successful professional in my field.” (Mastoor Al-Kaboody, Yemen) -”My time at NAU will help me achieve my goal to be a first-class specialist in the field of language teaching. I’ll be able to train other specialists and contribute the knowledge gained at NAU to the future development of education and the economy in Uzbekistan.” (Anastasiya Bezborodova, Uzbekistan) -”My NAU experience has exposed me to opportunities for professional growth that extend well beyond the classroom. I’m certain that the valuable education and professional skills gained at NAU will carry me through my career, during which I’ll be able to enhance, promote, and contribute to TESL in South Africa and make a difference in my professional community.” (Kelello Thamae, South Africa) -”My Fulbright experience has contributed to my academic, professional, social, and personal growth. The challenges faced make me a stronger person. As a result, I’ll be able to share the skills and information gained, adapted to the Kyrgyz education system, with my peers, colleagues, and students for years to come.” (Altynai Abdukarimova, Krygyzstan) Fredricka L. Stoller is professor in the Department of English Ming Cuisine (continued from page 6) for a cultural observer of China to understand that food and cuisine play roles beyond that of merely fulfilling nutritional needs. Over the past three years, I have led three study-abroad trips to Suzhou, China, a southeastern city famous for its garden and cuisine cultures. When taking students to banquets, I ask them to reflect upon the menu, the seating order, the toasting language, and other customs, and try to relate these observations to whatever bit of Chinese culture they may understand. While teaching LAN 399, a survey course of Chinese civilization and history, I briefly cover the topic of sumptuary laws and raise questions such as, Who is to use what utensil made of what material under what occasion? Correlating facts the students know, and the familiarity with history that they gain from books and lectures, deepens their understanding of the structure of social hierarchies of imperial China. A global education requires that students learn not only about themselves in relation to a global context but also seek to gain cultural insights through the dominant and not-sodominant features that can mark cultural distinctiveness. It turns out that the cuisine of a particular region or place, and how it is negotiated, can speak volumes about a culture. Never again should we take a superficial perspective on the range of cuisines to which we are fortunate to be exposed. They each tell unique stories that involve history, religion, lifestyles, and values. Most important, however, they tell stories of the human experience, and, ultimately, offer insight into who we are. Xiaoyi Liu is a lecturer in the Department of Global Languages and Cultures Fall 2013 NAU GLOBAL 17 18 NAU GLOBAL Fall 2013 Global Perspectives (continued from page 3) study the connections of one place to another. For much of my life I have been interested in how plant communities change through time and what specific processes are important in driving that change. These processes include climate, fire, insect infestation - and for the last few thousands of years, humans. This interest has led me – along with my students and others – to try to better understand how environments have changed not only here in western North America, but also to be able to place this understanding in the greater global context. Perhaps the relationship between ecology and geology, both local and global, is better realized through using an example. It is difficult to find a place on Earth that has not been affected by human activities over long periods of time. Our species has been particularly good at changing the landscape to best suit our needs. One way that paleoecologists can deduce the history of human impact over time is to look at the record of activities as found in the sediments of lakes and bogs. Muds and other deposits accumulate in the bottom of lakes over time and those muds include pollen and seeds from plants, and soils and other particles from environments near the lake. If in the past, a society specialized in, say, farming, animal herding or mining, evidence of those activities would end up in the lake. Taking a sediment core from that lake and studying the fossil remains allows paleoecologists to reconstruct the changes in the environment through time. Ecology and geology, combined. Even though cultures differ from one place in the world to another, we can learn volumes about our species and our relationship to Earth’s environment by comparing the records (continuation of articles) (continuation of articles) of human impact from different locations. For example, in Spain we have been working with our Spanish colleagues in both the Sierra Nevada and in the Pyrenees examining sites that help us understand the landscape changes associated with human activities during the last 6,000 years. In Norway we are examining sites that are in association with the first Nordic inhabitants that settled in far northern Norway at the end of the last ice age (about 11,000 years ago), and whether they had any impact on the landscape at that time. Looking at the charcoal particles from a lake core, we are studying the potential impact of the ancient Mayan culture on forest management and agriculture in the Yucatan Peninsula We can learn much about our future by studying how human societies the world over have responded to changes in the past. Religious Objects (continued from page 9) strive to educate their visitors about the world’s cultures; indeed, American museums receive 850 million visits annually (http://www.aam-us. org/about-museums/museum-facts). Efforts by museums to aid people in understanding world cultures, appreciating cultural differences and similarities, are of enormous importance. Bruce M. Sullivan is professor of comparative study of religions and Asian studies in the Department of Comparative Cultural Studies Astronomy as Perspective (continued from page 12) possibilities for the future. It is critical to help our students learn to navigate these international waters, capitalizing on access to people around the world while meeting individuals from other cultures in order to share and better understand others. The measure of our success will be in training globally competent students who will succeed in walking this path. In modern astronomy, it is impossible to achieve important astronomical advances without collaborating with scientists from around the world. In turn, these international collaborations allow us to answer questions that are common to all humanity. And yet, despite our common scientific and technical ground, the way we understand problems and our approaches to problem solving may vary as a result of cultural differences among researchers. As global citizens, we must learn to work with these differences to achieve our goals. R. Scott Anderson is Professor in the School of Earth Sciences and Environmental Sustainability David Trilling is associate professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy of Mexico. And closer to home, we have focused on the last 1000 years of environmental change along the California coast, where we are interested in the relative environmental impacts of Native American peoples prior to the colonization by the Spanish, and the large changes associated with the Spanish Mission system. It’s all connected – time and space, ecology and geology, the local and the global. We have a saying in paleocology – The Present is the Key to the Past, the Past is the Key to the Future. We can learn much about our future by studying how human societies the world over have responded to changes in the past. If we do not take this global approach we can only envision a limited set of Sprechen Sie STEM? (continued from page 4) sight is that engineers and scientists may actually learn language differently, due to a more analytic approach to problems and learning than students from other majors. This suggests that not only changes in content but also in the kinds of exercises presented in foreign-language curricula may be needed to maximally accelerate foreign-language learning for STEM majors. Finally, the need to incorporate complex content from engineering and the sciences into a STEM-oriented foreign-language curriculum raises the question of how such materials could be effectively developed, presented, and taught by faculty in the modern languages who, of course, are not themselves engineers and scientists. Efforts to answer these questions to date have been haphazard and informal, with individual language instructors at a handful of institutions around the nation developing and experimenting with specialized course content. In an effort to organize these efforts into a vibrant new area of language pedagogy, Northern Arizona University’s Center for International Education (CIE) recently hosted the 1st Annual Workshop on Languages for the STEM Disciplines. Supported by funding from the Goethe Institute, the workshop brought nine innovators in developing STEM-oriented materials and techniques for German instruction from around the nation to the NAU campus September 19–22. The main goal of this intensive workshop was to establish a foundation for the “Languages for STEM” area by tackling three central tasks: - Concisely define the novel challenges raised by teaching language to STEM majors and articulate the areas in which new pedagogy must be developed to meet these challenges. - Inventory the techniques and materials already developed by forward-looking language instructors, using these concrete examples as a basis for defining the complete spectrum of concepts, vocabulary, and linguistic skills that must be mastered by STEM majors. This defines a pedagogical framework that must be fleshed out with actual exercises, projects, and other learning materials. - Develop a roadmap for rapid coordinated development of missing curricula and teaching materials to populate the framework, including work plan, technological infrastructure, and funding strategy. The vision developed by workshop participants, called the STEMINTegrate model, was centered around a first draft of a hierarchical knowledge schema for representing the specialized STEMoriented language concepts that will be critical for competent STEMoriented communication. The schema focuses on numbers, counting, and other basic STEM-oriented vocabulary at the lowest level; moves to second-order concepts like measurement, calculation, and description of complex machines or laboratory instruments; and then on to advanced descriptions of complex STEM processes across different time scales and tenses. To support efficient development and sharing of teaching materials, the team outlined a vision for a sophisticated web-based portal and archive to serve as the cornerstone of the Language for STEM community. In this portal, language instructors could collaborate with STEM professionals from around the world to develop, post, and review new course materials, indexed by skill level, nature of concepts being taught, and specific STEM discipline that the materials are based on. The overall goal is that any foreignlanguage instructor at any university in the United States should be able to very quickly download curricular plans and course content to develop a STEM-oriented language course customized to the particular mix of STEM majors in an upcoming semester. Adding foreign-language training offers ambitious STEM majors significant competitive advantage in tomorrow’s global STEM labor market, but it can be challenging with a program of already quite dense study in engineering and the sciences. This goal places a premium on efficient language learning tailored precisely to the very practical applied language (learning goals of scientists and engineers), vocabulary and processes in each major. The STEMINTegrate model, once completed, will provide a basis for revolutionizing language instruction for the STEM disciplines, allowing faculty to easily share their best practices, course materials, and curricula with colleagues nationwide. This will allow easy integration of STEM-specific teaching in any foreign-language program, but will be particularly useful for intensive STEM internationalization initiatives like Northern Arizona University’s own Global Science and Engineering Program (GSEP; www.nau. edu/gsep), which incorporate foreign-language learning as a central element of internationalized STEM degree programs. Eck Doerry is faculty director of the Global Science and Engineering Program and Professor of Computing Science Fall 2013 NAU GLOBAL 19 International Visiting Scholars at NAU, Fall 2013 VISITING SCHOLAR DEPARTMENT AKERELE, Oluwatoyosi HOST FACULTY HOME INSTITUTION Criminology & Criminal Justice ANTONCIC, Iva Mathematics & Statistics CAO, Zhiling CIE and Business CASABURI, Giorgio Biological Sciences CHEN, Yongjin CIE and English CUI, Zhanqin CIE and Engineering DE ALBUQUERQUE, Fabio Forestry EJARQUE MONTOLIO, Earth & Environmental Ana Belen Sciences GARCAI MEDINA, Nagore Forestry GUO, Yingjie CIE and English KANG, Yongjin CIE and Engineering LI, Hong CIE and Engineering LI, Jun CIE and Engineering LIANG, Hongmei Applied Linguistics LIU, Yunlin CIE and Engineering MOMMERT, Michael Physics & Astronomy NIE, Zuoxian CIE and Engineering PENTEADO, Paulo Fernando Physics & Astronomy SALMINEN, Joni Business SASAKI, Akiko College of Education SONG, Jiling CIE and Political Science SONKAR, Kanchan Chemistry TANG, Pan CIE and Health Sciences TANG, Yaocai CIE and English VAN GROENIGEN, Cornelius Jan Merriam-Powell Ctr for Environmental Research WU, Bei CIE and Business YANG, Qingguo CIE and Communications YANG, Hai Business YU, Li Engineering Robert Schehr Griffith College Dublin (Ireland) Stephen Wilson Ding Du James Gregory Caporaso William Crawford Allison Kipple Paul Beier Scott Anderson University of Primorska (Slovenia) Hunan Institute of Technology (China) University of Naples Federico II (Italy) Hefei University (China) Xi’an Shiyou University (China) N/A Universidad de Granada (Brazil) Universite Blaise Pascal (France) Matthew Bowker John Rothfork Chun-Hsing Ho Otte Deiter John Tingerthal Douglas Biber Allison Kipple David Trilling Eck Doerry David Trilling Talai Osmonbekov Gretchen McAllister Robert Poirier Matthew Gage Roger Bounds Okim Kang Bruce Hungate Universidad Autonoma de Madrid (Spain) Shaanxi Normal University (China) Xi’an Shiyou University (China) Hefei University (China) Ningbo University of Technology (China) South China Normal University (China) Southwest Jiaotong University (China) Institute for Planetary Research (Germany) Fujian University of Technology (China) Universidade de Sao Paulo (Brazil) Scientists to the World Organization (Finland) N/A (Japan) Shaanxi Normal University (China) Centre of Biomedical Magnetic Resonance (India) Hefei University (China) Beijing International Studies University (China) Trinity College (Ireland) Xiaobing Zhao Norm Medoff Ding Du Philip Mlsna ZAGO, Raffaele ZHANG, Baoshan ZHAO, Chunjiang ZHAO, Xiaoyan ZHAO, Lu ZHAO, Yuhua ZHU, Ruiqing Douglas Biber Matthew Gage Philip Mlsna Nancy Paxton Rick Stamer Ding Du Luke Plonsky Yunnan University of Finance & Economics (China) Hefei University (China) Central China Normal University (China) Nanjing University of Information Science & Technology (China) Universita Degli Studi Di Pavia (Italy) Shaanxi Normal University (China) Hefei University (China) Jinan University (China) Shaanxi Normal University (China) Beijing International Studies University (China) Beijing International Studies University (China) English CIE and Chemistry CIE and Engineering English CIE and Music Business CIE and English NAU GLOBAL Center for International Education cie@nau.edu http://international.nau.edu/ Fall 2013 PAGE 20