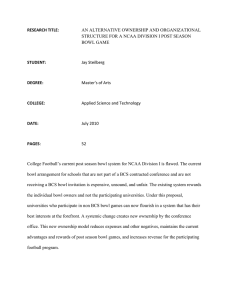

Conflicts of College Conference Realignment: Pursuing Revenue, Preserving Tradition, and Assessing the

advertisement