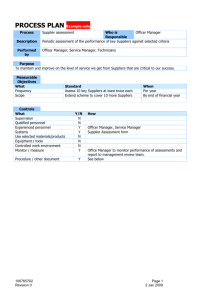

Understanding the Role of Government and Buyers in Supplier Energy

advertisement