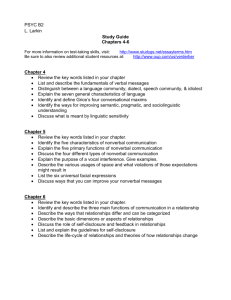

presented on 6

advertisement