Document 11951173

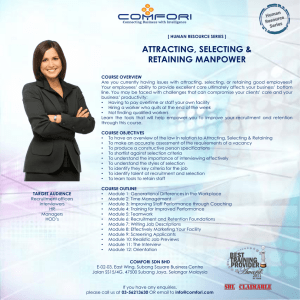

advertisement