Document 11951124

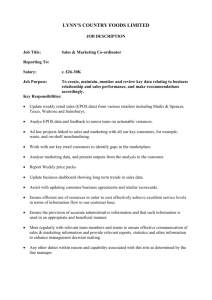

advertisement