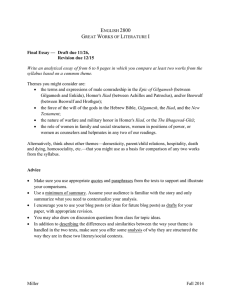

ESSAI

advertisement