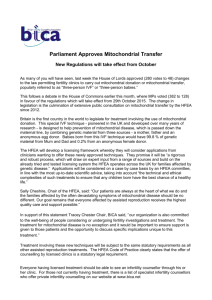

Mitochondrial Donation

advertisement