Stakeholder Perceptions of the Determinants of Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences

advertisement

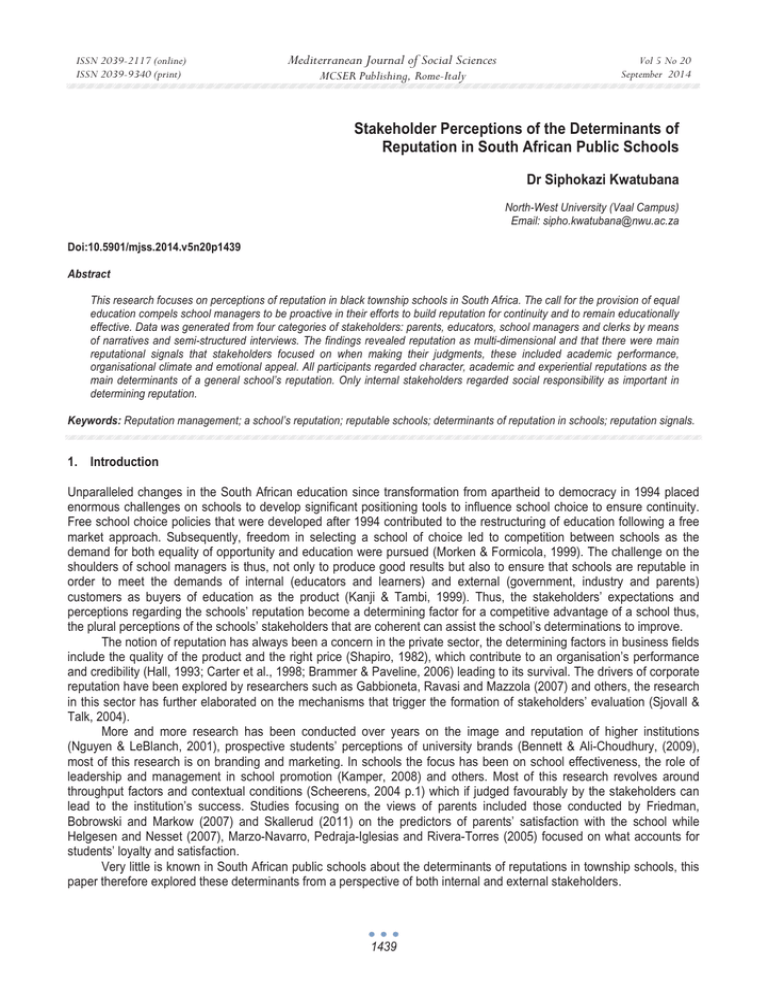

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 Stakeholder Perceptions of the Determinants of Reputation in South African Public Schools Dr Siphokazi Kwatubana North-West University (Vaal Campus) Email: sipho.kwatubana@nwu.ac.za Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n20p1439 Abstract This research focuses on perceptions of reputation in black township schools in South Africa. The call for the provision of equal education compels school managers to be proactive in their efforts to build reputation for continuity and to remain educationally effective. Data was generated from four categories of stakeholders: parents, educators, school managers and clerks by means of narratives and semi-structured interviews. The findings revealed reputation as multi-dimensional and that there were main reputational signals that stakeholders focused on when making their judgments, these included academic performance, organisational climate and emotional appeal. All participants regarded character, academic and experiential reputations as the main determinants of a general school’s reputation. Only internal stakeholders regarded social responsibility as important in determining reputation. Keywords: Reputation management; a school’s reputation; reputable schools; determinants of reputation in schools; reputation signals. 1. Introduction Unparalleled changes in the South African education since transformation from apartheid to democracy in 1994 placed enormous challenges on schools to develop significant positioning tools to influence school choice to ensure continuity. Free school choice policies that were developed after 1994 contributed to the restructuring of education following a free market approach. Subsequently, freedom in selecting a school of choice led to competition between schools as the demand for both equality of opportunity and education were pursued (Morken & Formicola, 1999). The challenge on the shoulders of school managers is thus, not only to produce good results but also to ensure that schools are reputable in order to meet the demands of internal (educators and learners) and external (government, industry and parents) customers as buyers of education as the product (Kanji & Tambi, 1999). Thus, the stakeholders’ expectations and perceptions regarding the schools’ reputation become a determining factor for a competitive advantage of a school thus, the plural perceptions of the schools’ stakeholders that are coherent can assist the school’s determinations to improve. The notion of reputation has always been a concern in the private sector, the determining factors in business fields include the quality of the product and the right price (Shapiro, 1982), which contribute to an organisation’s performance and credibility (Hall, 1993; Carter et al., 1998; Brammer & Paveline, 2006) leading to its survival. The drivers of corporate reputation have been explored by researchers such as Gabbioneta, Ravasi and Mazzola (2007) and others, the research in this sector has further elaborated on the mechanisms that trigger the formation of stakeholders’ evaluation (Sjovall & Talk, 2004). More and more research has been conducted over years on the image and reputation of higher institutions (Nguyen & LeBlanch, 2001), prospective students’ perceptions of university brands (Bennett & Ali-Choudhury, (2009), most of this research is on branding and marketing. In schools the focus has been on school effectiveness, the role of leadership and management in school promotion (Kamper, 2008) and others. Most of this research revolves around throughput factors and contextual conditions (Scheerens, 2004 p.1) which if judged favourably by the stakeholders can lead to the institution’s success. Studies focusing on the views of parents included those conducted by Friedman, Bobrowski and Markow (2007) and Skallerud (2011) on the predictors of parents’ satisfaction with the school while Helgesen and Nesset (2007), Marzo-Navarro, Pedraja-Iglesias and Rivera-Torres (2005) focused on what accounts for students’ loyalty and satisfaction. Very little is known in South African public schools about the determinants of reputations in township schools, this paper therefore explored these determinants from a perspective of both internal and external stakeholders. 1439 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 2. Literature Review This section explores the various definitions of reputation, and the internal and external determinants of reputation. 2.1 Definition of reputation Marconi (2001:20) and Sherman (1999) define reputation as opinions, beliefs or views of people about a person or an organisation (p.11) over time and Schultz and Werner (2005) highlight the importance of reality about a situation. Reputation therefore, consists of (1) image, which entails the opinions or the overall impression about the school, (2) identity including what internal stakeholders think the school is about and (3) personality, pertaining to what the school is all about. The two most important dimensions in corporate reputation therefore, include image and identity thus, there must be harmony between the perceptions of the external and internal stakeholders on their evaluation what the school is about. Disharmony in the perceptions of these two groups can dent the reputation of a school as an evaluation or judgement is a highly efficient mechanism of social control based on the results that may either be treasured or disparaged. What is evaluated according to Wartick (1992) is the organization’s ability to meet the demands and expectations of the people it serves and its consistency in providing service in a trustworthy and reliable manner (Bennet & Rentschler, 2003). Meffert and Bierwirth (2002, p. 190) indicate that there are stakeholder-specific reputations and a general construct of reputation. In this study reputation will be defined as an elusive worth, regard or respect given to an institution of learning based on the actual actions of the whole school. 2.2 Determinants of reputation According to Karaköse (2008), perceptions of stakeholders tend to focus on broad dimensions such as academic output measures, general effectiveness of the school, good leadership and management, learner performance, emotional appeal, parental and community involvement, learner support, staff attitude and motivation, physical environment, the behaviour of learners (Baneke, 2011:36) and communication (Botha, 2010). An external dimension according to Gabbioneta et al (2007) is emotional appeal, which entails the extent to which an institution is trusted, liked, admired and respected by the judges of reputation. Stakeholders prioritise their evaluations based on actions that they perceive as prominent to their specific interests and values. 2.2.1 Internal determinants of corporate reputation in school 2.3 Academic performance As indicated in the foregoing paragraphs, stakeholders have expectations that need to be met by institutions to be regarded as reputable. Neville, Bell and Menguc (2005) concur with this indicating that the impact of stakeholders on the institution occurs through formation of expectations that are directly linked to the institution’s performance. Gray (2004) opines that examination results are a measure of learning (p.187) and the reputation of a school is often evaluated based on academic results. The South African primary schools’ academic performance started being evaluated by means of the Annual National Assessment (ANA) in 2011. Grades three and six were marked and invigilated by teachers at schools and external verification was done by the Human Science Research Council; the Department of Basic Education. The ANA results in 2011 indicated poor performance in the majority of primary schools even after trial runs in 2008 and 2009. Learners performed poorly in both Mathematics and English, it was in 2012 and 2013 that improvement in the examination results started to be realised. The improvement itself is problematic in that only internal verification was done by the Department of Education and schools, thus reporting unverified scores. The lack of external verification of the ANA results according to Spaull (2013 p. 4) reduces much of their value, thus making these tests an unreliable measure of performance thereby failing to promote societal trust. The perceptions of the media Mail & Guardian (2009), Mail & Guardian (2012) is that poor performance in ANA is a “scandal”, the results “do not make sense” thus, an indication of an unfavourable reputation. From the foregoing paragraph it can be deduced that it is only in principle and not in practice that ANA provides standardised indication of learning in primary schools. However, the Department of Basic Education determines performance and under –performance of public primary schools using standards set by a district on a particular year 1440 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 based on the ANA results. For an example the National target for 2013 was 60%, this meant that at least 60% of the learners in a class must get 50% and above. The provinces, districts and schools have to set their own targets, the provincial target for Gauteng was 50%. A school that performs below the set standard is thus considered underperforming, consequently, stakeholders oriented towards performance as a perception factor will pass judgement on these schools results. Another problem regarding the ANA results is that they are not published publicly as they are not externally handled. The parent and the learner as customers are therefore, at a disadvantage as they are unable to determine the quality of learning at their schools because of lack of such data. The secrecy surrounding general information about the ANA results (1) deprives the parent of an opportunity to make an informed judgement regarding the reputation of such schools, (2) hinder the facilitation of the endorsement of corporate evaluations across stakeholders and (3) thus, deprive the very department of increasing the creation of salience of actions and preventative measures of which schools could form part. Based on the report by the World Economic Forum (2014), the state of South African education at school level is worsening, putting it at 146th place out of 148 countries, calling for an urgent overhaul of the education system. Grade 12 learners are externally evaluated and sit for nationally standardised examinations. Matric students get an endorsement of Bachelors to pursue studies in universities, very few students get this validation as the majority only qualify for Diplomas and others for Further Education and Training. Spaull (2013 p. 5) indicate that only 50% of the learners reach matric and 80% of those who sit for examinations pass whilst only 24% of those who pass qualify to study at a university. The classification of all public schools as either performing or under-performing is founded on the examination results. According to Louw, Bayat and Eigelaar-Meets (2012), under-performing high schools are those that fail to achieve a Grade 12 pass rate of more than 60% (p. 1). Parents in South Africa are aware of High schools that perform well and those that are struggling, basing their judgement on matric results. High academic performance does not happen in isolation, there are a range of factors that contribute to it including good leadership and management which also impact on staff motivation, commitment and working conditions (Leithwood et al 2006 p. 4). 3. Good Leadership and Management Good leadership and management are regarded as key characteristics of effective schools, while bad leadership and management are documented as features of ineffective schools (Matthews & Sammons, 2004; Mulford et al., 2004). Research by Roberts and Roach (2006), Bush et al (2010); and Christie (2010) show that reputable schools are developed by effective, reputable and prestigious leaders and managers. The reputable principals of schools can therefore add value to the reputation of schools they manage and their allure may, according to Hayward et al (2004), help to garner internal and external support for the implementation of the schools’ strategies. Leadership is the ability to exert influenced over members of a group or organisation to work persistently towards achieving a common goal. This definition indicates that the influence is done for a certain purpose, following a deliberate process for creation of a common vision (Lumby et al., 2008) translating this vision into a reality that can be sustained. Stoll and Fink (1996) argue that the concept of leadership has progressed gradually from managerial approaches which focus on results, via transactional approaches that focus on staff efficiency to transformational approaches with an emphasis on attitudinal change. Bass and Riggio (2006).state that the transformational leader aspires satisfaction of higher-order growth needs by improving, achieving, demonstrating certain attributes such as being optimistic, excited about goals, believing in a set vision and committing to develop and mentor followers while a transactional leader focuses on the mutual reward theory, rewarding followers who reach agreed levels of performance and intervening when standards are not met. A research conducted by Day, et al (2011) found that successful schools use a synergy of these two theories. Good leaders draw from the following repertoire of behaviours autocratic, delegators, collaborative, communicators, task oriented, risk takers, relational, nurturers, controllers, stabilisers and intuitive (Irby & Brown, 2001). Two dimensions of leadership behaviour are apparent from these examples: employee oriented with an emphasis on interpersonal relationships and production oriented emphasising task aspects of the job. Management as opposed to leadership is characterised by maintaining the status quo ensuring continuity of the existing pattern. Preoccupation with activities that helps to maintain the existing situation such as planning, budgeting, monitoring and evaluating and facilitating processes becomes the order of the day. This focus on processes contrasts that of leadership where motivation, coaching, building trust is much more important. The two concepts are however, interwoven, effective managers must be able to go beyond managerial tasks to inspiring and mobilising their followers to avoid being undermined by lack of humanity, adaptability and creativity. 1441 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 Reputation is an unpredictable process which cannot be judged only using one dimension, thus the creation of enabling conditions for effectiveness in the implementation of strategies becomes imperative. 4. Organisational Climate and Physical Appearance of the School Organisational climate is about the feeling of the people about the culture that has been created through routine behaviour, policies, practices and procedures that affect their attitudes (Dryfoos, 2000). The management of reputation depends on factors schools employ to maintain a positive climate. The first factor includes effective corporate communication between stakeholders. A collaborative environment and open communication contribute to successful school improvement initiatives thereby leading to a positive image and in the process according to Dickinson-Delaporte et al (2010) a confidence-based relationship is also built The second factor is that of developing and implementing policies that are permitting mutual benefit rather than restricting it, conveyed to all stakeholders. Stakeholder involvement in the development and implementation of such policies according to Fullman (2003) can make them feel good about being part of the decision making and lead to commitment to the plan. The third factor focuses on people who operate more like a community, thus avoiding a negative climate of high disengagement, high hindrance and low esprit which is detrimental to any school’s reputation. The building of trust and confidence as a fourth factor becomes imperative as it relates to having a high regard and respect for every stakeholder. The fifth factor pertains to the modelling of good behaviour which is consistent with the school’s vision (Fullman, 2003). The last factor which is the sixth pertains to a focus on educator morale and job satisfaction (Keefe, 2003 p. 46). A positive school climate can result in high academic achievement as it influences motivation and job satisfaction. It is associated with fewer behavioural problems as a sense of belonging is fostered. 5. External Determinants of Corporate Reputation in School 5.1 Emotional Appeal According to Mahon and Wartick (2003) individuals form impressions or construct an institution’s reputation primarily through direct experience with the institution and or its products and services. Petrokaite and Stravinskiene (2013 p. 497) concur with this statement adding that the stakeholders’ experience is a static element of reputation. The primary driver of stakeholders' attitudes and their future actions therefore becomes their direct experience (Kazoleas, Kim & Moffitt 2001) which appeals to the quality of the product and generalised evaluation of the institution’s performance (Helm, 2007) this exposure to a school’s activities can lead to a parallel process of building a rapport with stakeholders while managing the reputation. Alternatively where there is no direct experience, stakeholders form opinions mediated by other people's opinions and influence (Bromley, 2000) for an example they will turn to reputational information (Mahon & Wartick, 2003; Puncheva, 2008), which can be offered by media, government information or acquaintances or increasingly commonly by online discussions. In most cases the reputational information is formed by rumors about incidents that are not necessarily true, leading to unnecessary dents to their reputation which could have been avoided. In the absence of experiential reputation according to Goates (2008) stakeholders resort to hearsay reputation which is less trustworthy compared to experiential reputation. A School can come up with different ways of giving parents a direct experience, the Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions and Equity (CREATE) (2011) suggests that instead of giving progress reports only at the end of term, schools should host parents’ days more often to make teacher-parent-learner conferences possible also on sports days or market days. The study further suggests that policies which promote parental participation at school governance level must be supplemented with policies which encourage parents to play complementary roles at the levels of teaching and learning thereby bringing parents and the broader community together to support teachers in creating a conducive and quality learning environment that allows for experiential reputation. In summary, the pursuit of the multiple goals discussed in the foregoing paragraphs within multiple environmental constraints and time frames (Hall, 1987 p.28) become an impossible realisation for some schools leading to loss of reputation. 1442 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 6. Research Methodology 6.1 Instrument An exploratory qualitative research method is known for its ability to generate data when there is not much known about a concept. A phenomenological study was preferred because of its principle of multiple data collection tools. Scholes and Clutterbuck (1998, p. 237) indicate that there is no effective tool for comparing, different stakeholders’ perceptions of an institution about its reputation, thus, narratives were used to provide insights on what participants perceive as determinants of reputation in their schools. Participants narrated key events or highlights that they based their judgement on when determining the reputation of their schools. The individual in-depth interviews allowed me to delve profoundly into social and personal matters relating to their judgements and also control the orientation, focus and sequence of the interview by means of probing questions (Butler, 1997). This was an emergent design as the interview moved from being structural to a more conversant design, opening up other avenues for analysis (Wright, 2008:66). 6.2 Participants The empirical research was conducted in the Free State Province in Sasolburg and Frankfort parts of the Fezile Dabi District Municipality in South Africa. Participants were purposefully selected thus, sampling with a particular purpose and a certain requirement (Maree, 2007), as the selection centered around schools with the highest enrolment of learners in their communities and high schools with high matric pass rates. As image is developed over years it was necessary to select participants who had been with the school for more than 5 years. Participants composed of four stakeholder groups from 4 schools (2 primary and 2 secondary) in Free State province as indicated in Table 1 below. Table 1: Profile of the research sites School A: Primary B: Primary C High School D High School Date established 1982 1994 1977 1999 Enrollment in 2012 854 1415 Gr 1 only (244) 1442 1175 Educators 26 44 55 40 Participants 5(Principal, HOD, educator, clerk, parent 5(Deputy principal, HOD, educator, clerk parent 5(HOD, 2educators, clerk, parent) 5(Deputy Principal, HOD, educator, clerk, parent) All schools were in existence for more than 15 years. All participants (7 school managers, 5 educators, 4 clerks and 4 parents) (n=20) were interviewed individually, educators at school after teaching time and parents at their homes on weekends. Participants are indicated in codes developed from their positions P for principal, H for HOD, E for educator, C for clerk, DP for deputy principal and Pa for parent, for an example a principal in school A is PA1 and an educator in school C is EC9. Participants were informed about their rights before the interviews started. All school managers and educators were comfortable with being interviewed in English. All responses were captured verbatim, even those whose participants requested to be interviewed in English but switched to their languages when responding to some questions. Data that was in Sotho was translated to English with the help of assistant researchers. The data was later back translated and a comparison between the originals and back-translated versions was made (Maneesriwongul & Dixon, 2004:176). 7. Findings and Discussion It was important to record both internal stakeholders’ (educators and SMT members) responses representing employee specific perceptions and external stakeholders’ (parents) representing customer specific perceptions. The perceptions on the participating schools’ reputation or lack thereof is based on what the schools do and what the participants say the schools do, thus ensuring congruence between action and message. 7.1 Leadership and management Effective leadership was an important aspect of reputation according to participants from three schools, activities that 1443 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 helped in maintaining good relationships with parents and educators were kept. In two schools principals were mentioned as “known” and “energetic”. The literature highlights the value added to an organisation by principals who are prestigious. we are fortunate to have visionary leaders who are known and who have knowledge of the policies of the department (EB5). I really thank God for the kind of leadership we have in this school, they are energetic and have a vision (CB7); our deputy principal assists in coaching learners (DPD16); the deputy principal is a workaholic, you cannot help it but work if he is around (HD13) Finances in this school are used according to policy. Participants revealed being satisfied with the level of communication within their schools and between schools and parents. Giving feedback to parents in issues of finance and academic performance strengthens trust, keeping open communication with them. Channels of engagement were created between managers and educators an indicating approachability of the SMT in these schools. The SMT of the school listens to the advice given by the staff members and supports staff members with everything (HA2); 7.2 Corporate communication Channels of communication with parents include planned and unplanned meetings creating an opportunity for educators to show not only their commitment to teaching and learning but also meet the growing demand for transparency in activities. A favourable possibility of building a rapport could be created in meetings that are constant, as according to Petrokaite and Stravinskiene (2013 p. 499), these meetings would determine visibility. Communication with parents is very good we invite them for sectional meetings to come and check the work of learners (CC9); we call parents for emergency meetings (CC9); the principal shows the bank statement to the members (CE2); we issue out reports now and again (EA2); everything is transparent and on top of the table (EB5); the finance committee gives a report to the SGB members and parents regarding expenditure, The achievements are communicated to parents, participation in extra mural activities seems to be one of the best attributes of the participating schools in which parents are invited to celebrate. These celebrations add not only to constant communication with parents but also visibility of schools. This is part of what these schools can do and thus reveal their capability reputation, thereby serving as reputation promoting actions. We show them the trophies in parents’ meetings (EA2); trophies are shown to parents when committees are giving report, parents also get awards for helping us with learners (PA3); parents are invited to a prize-giving ceremony for both educators and learners (HA1); learners who perform up to provincial level receive awards (CC9); we love celebrations, if we won a trophy we start celebrating at the assembly, winners and the educators who were part of the activity will be thanked in front of everyone (HC11); when we have money the principal throw a party for the team that brought a trophy, parents are invited when learners are given awards (EC12). School C had to involve parents to control an unpleasant situation, thus continuing with constant communication even in times of crisis. Parents were involved throughout, indicative of assumption of responsibility and commitment in resolving the problem and an opportunity to promote parental cooperation and commitment. Engagement of parents in such issues could create a platform for open consistent communication between the two parties. We had problems with learners that were fainting, believed to be caused by Satanism, parents were flocking to the school, the principal had to talk to them over the community radio (HC11); talking to parents helped, we were guarding against situations where this thing is blown out of proportion (HC11); parents assisted us with fixing areas that were burnt during the time when students tried to burn down the school (HC11); we do not have incidences of gangsterism or children that smoke dagga in the toilets, if we had parents would help, our relationship with them is good (EB5); 7.3 Good behavioural tendencies Values according to Mishina, Block and Mannor (2012 p. 460), determine the character reputation of an institution, which is also evident in good behavioural practices revealed below. Participants revealed maintaining good standards for practice including commitment and responsibility when dealing with parents. Parents also emulate the behaviour that is shown to them by educators. Good behavioral tendencies if well manage and done consistently over time could lead to a trustful relationship between parties. All educators attend general meetings and report at 07:30 in the morning, parents and educators sign attendance 1444 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 registers as proof of attendance (CC9); if a parent is unable to attend, he/she has to report, and arrange a specific day she/he can come to school to check for their children’s progress (EB5); we never have problems of parents who do not attend meetings, almost all of them come (HA1); in every parents meeting we have a lot of parents, we do not have problems of parents not attending meetings (HD13) Participants also revealed a character reputation of participating schools which included values such as accountability, hard work and commitment which enabled schools to achieve their goals. Educators know that they must be in class teaching learners. Educators here work very hard, I come to school at 7h00 everyday, to open the gates for the food handlers and the teachers that come early, I usually find them already waiting at the gate (EC10); in other schools educators live at 14:30, it is 15:00 now and we are still at school, we leave at 16h00 everyday because educators want to excel in everything they do, we are not paid for starting early, it is the sacrifice we make (CB7); educators work very hard here (HA1); teachers here work very hard, after 6h00 you start seeing teachers coming to school (PaB18); we have classes for an hour every afternoon (CC9); we continue with classes during weekends and holidays, we ask for assistance with Maths and Science from people who are experts to help us (HC11); educators give their best when it comes to teaching (EC12); we are blessed with good educators in Grade 11 and 12 who do their best (HD13) It seems that educators model a good behaviour for learners who become inspired to work hard as well. educators do their work whole-heartedly, this encourages learners to work hard, we work as a team in this school, teachers in Grades 8-11 assist the Grade 12 teacher in his subject (HC11). Both educators and parents show being socially responsible, a tendency directly linked to a school’s behaviour and actions assuming commitment to alleviation of social problems in their communities. Although social responsibility in these schools is coherent with the expounded internal values above, it is also triggered by pressure from the communities, including high rate of unemployment and poverty. A school that shows coherence between its values and what it does can be trusted (Vidal & Torres, 2005 p.18) Five educators in our school collect school uniform from those who completed matric for learners who are struggling, we do this every year (HD13); no we don’t pay them (parents who help out with cleaning), they are doing it voluntarily but we give them vegetables from our school garden (HB6);. The good behaviour tendencies are evident in how external stakeholders assist and support the participating schools. All these stakeholders had a direct experience with their schools, as according to Goates (2008), stakeholders are thus exposed to experiential reputation which is more trustworthy than hearsay. Involvement of all these stakeholders is of utmost importance as they can easily influence the reputation of these schools by either communicating positive or negative messages to the communities and potential students. Reputation of school is up held by everyone including factotum (EB5); parents help the school with cleaning. They share and they know who is cleaning on Mondays, Tuesday etc (HB6); parents who have soccer, netball, volleyball skills come on Wednesdays to assist us with learners during sports activities (EB5); the SGB ensures that everything goes accordingly here at school, how finances are handled, employment of teachers and general maintenance of the buildings (EC10); the community enables something called “sense of ownership”. They are jealous of our school, they feel that they are watch dogs of our school. At times you hear them saying principal the lights were not on last night, that alone shows they really care (EB5); we develop policies in such a way that we include everybody (EB5). The responses of the participants revealed that schools’ identity was formed by their participation in sporting activities at both local and provincial levels, thus being known for being the best in different sporting codes, this attribute does not only reveal the visual element of these schools but also their distinctiveness. Our target each year is to reach provincial level when competing in extra-curricular activities (DPB8); we get trophies every year, we got two this year, we have different sporting codes to try to accommodate all learners, our children excel in chess (CC9); we got these trophies over years, every year we win some trophies, we are the best in soccer, netball, choral music and drum majorettes (HC11); this school is the best in sports and choral music, everyone around here knows that (PaC19). Participation in extra-curricular activities in these schools is a norm, these activities glue the whole school community together as all stakeholders are either directly or indirectly involved. In addition school B made a mark in winning a prize for academic performance. As stories about such achievements spread, the school becomes more visible and a positive image is thus formed. In this school we win, we were awarded a R100 000 rand because of being the ‘best academic performing school, our school is doing well, we participate up to provincial level (EB5) 1445 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 The large number of learners registered in these schools can be attributed to corporate reputations of the participating schools as indicated above. We have never experienced problems with decreasing number of learners where this can lead to redeployment of teachers, we sometimes turn down applications because of lack of classes (EC10); during administration time, every parent wants to register his or her child at this school (EB5); we never experienced decreasing number of learners, no one has been redeployed in this school ever since I started working here 10 years ago (HC11); This is a well-known school, every parent wants to enrol his or her child here (PaB18); The surroundings of the school were also regarded as important by both external and internal participants. Beautiful surroundings are attractive to passers-by and inviting and inspiring to internal stakeholders. Surroundings that are filthy and uncared for can project a bad image of the school to external stakeholders. We make an effort to make our school look beautiful, the surroundings must tell you stories about the kind of a school you are in. that feeling of being somewhere, heavenly (DPB8); this school is beautiful, sir, it is nice to work in such a school (EB5); the surroundings are not as clean as they used to years back, it is because there is only one caretaker (PaC19) Reputational troubles were indicated in two participating schools, emanating from behavioural problems and lack of parental commitment. The situations impact negatively on teaching and learning and the smooth running of the two schools. Mis-behaviour of learners can dent the image of the school if not resolved for a long time, this situation can bring teaching and learning to a halt, leading to a decrease in pass rate. The schools’ ability to meet the demands and expectations of its stakeholders therefore could be in jeopardy. We were labeled the worst school because of gangsterism, no one gave us a chance to explain, this problem of learners walking long distances to school was beyond the school, but no one cared (HD13); we struggle when it comes to SGB elections, parents in this school do not want to be members of the SGB, I have worked here for 9 years, I have seen this happening, parents attend in numbers after these elections (CC9); 7.4 Academic performance Stakeholders are particularly attuned to academic reputations of high schools. Observable characteristics of academic functioning of a school such as effective teaching and learning, extra classes, behaviour of learners, involvement of parents, pass rate are predictive of academic performance. Having positive academic reputation was associated with high pass rate. In the responses there was no differentiation between in results on whether more learners get entry to universities or not. Our Grade 12 results were 95.6% last year, we are doing well, we aim for 100% next year (EC12); our pass rate is good, schools struggle to beat us for the past 7 years we have been the best (CC9); last year the Grade 12 results were very good, we got 95.6% (EC10); one of my children is doing Grade 12 here, I decided to enrol her here, the Maths and Science teachers are the best (EC10); the school gets excellent results each year (EC10); parents love this school because it gets excellent results at the end of each year (HC11); the school is doing well academically (PaC 19); we never get less than 50% even when we had problems, last year we got 100%(HD13) 8. Concluding Remarks This study’s limitations include the small sample from which the data was generated, the findings can therefore not to be generalised. The sample was taken from schools that were perceived as performing well in Black townships, stakeholders from different school communities might differ thus, this study was exploratory in nature. As assumed by Fombrun and Wiedmann (2001) the finding of this study is that there were no large differences between the perceptions of different stakeholder groups, thus they came up with almost the same set of determinants of reputation. Improving reputation in black township schools is of utmost importance within the bigger picture of providing equal education in South Africa. The finding of this research indicates that the reputation of a school is multi-dimensional with different determinants. All four groups of stakeholders agreed on the importance of (1) behavioural tendencies which determine the character reputation of a school, including socially accepted values, (2) emotional appeal thereby rendering direct experience to parents and community members by involving them in the schools’ matters both good and bad, (3) customer value in building trust and confidence thereby enhancing credibility by using internal processes of reporting and stakeholder engagement and (4) academic performance of schools determining their academic reputation. 1446 ISSN 2039-2117 (online) ISSN 2039-9340 (print) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy Vol 5 No 20 September 2014 The activities the school engages in create either positive or negative-reputation signals. Internal attributes which have a positive effect on institutional image include a certain personality and a good leadership style (Kamper, 2008 p. 16), participation in extra-curricular activities and communicating with parents through corporate social reporting enable stakeholders to evaluate the school’s reputation. It is believed that it is these internal attributes that attract learners to the participating schools. Although the link between stakeholders’ reputation perceptions and their decisions to engage in a particular form of supportive behaviour for an institution has not been adequately explored (Cornelissen, 2000; Wartick, 2002; Ferris et al., 2002), all groups of participants indicated that the participating schools did not experience decreasing enrolments. Furthermore, educators and clerks were happy with the working conditions at their schools. Research indicates that employees love to be associated with reliable leading institutions with less threat of being in access and eventually deployed to other schools. This situation can translate to job satisfaction because of the good image of these schools. References Beneke, J.H. (2011). Marketing the Institution to Prospective Students – A Review of Brand (Reputation) Management in Higher Education. International Journal of Business and Management, 6(1): 29-44. Bothat, RJ. (2010). School effectiveness: conceptualising divergent assessment approaches. South African Journal of Education, 30(4) Cosser, M. (2002). Student choice behaviour. Human Sciences Research Council, Pretoria. Day, C., Sammons, P., Leithwood, K., Hopkins, D., Gu, Q., Brown, E. & Ahtaridou, E. (2011). Successful school leadership. Buckingham: Open University Press. Gabbioneta, C., Ravasi, D. & Mazzola, P. (2007). Exploring the Drivers of Corporate Reputation: A Study of Italian Securities Analysts. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(2): 99–123 Goates, N. (2008). Reputation as a basis for trust. Dissertation, Vanderbilt University. Hall, R. (1993). A framework linking intangible resources and capabilities to sustainable advantage, Strategic Management Journal, 14(8):.607-18. Hall, RP (1987). Organizations: structures, processes and outcomes. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. Irby, B.J. & Brown, G. (2001). A gender-inclusive theory: the synergistic leadership theory. Seattle, WA, . Kamper, J. (2008). A profile of effective leadership in some South African high-poverty schools. South African Journal of Education, 28: 1-18. Kanji, G. K. & Tambi, MBA. (1999). Total quality management in UK higher education institution. Total Quality Management, 10(1): 129153. Leithwood, K., Day, C., Sammons, P., Harris, A. & Hopkins, D. (2006). Seven Strong Claims About Successful School Leadership, Nottingham: National College for School Leadership Louw, W., Bayat, A. & Eigelaar-Meets, I. (2012). Play it again Sam: exploring grade repetition at under performing schools in the Western Cape. Available at: http://www.psppd.org.za/MediaLib/Downloads/Home/ResearchEvidence/Play%20it%20Again%20 Sam.pdf Date of access – 10/05/2014. Mahon, J. F., & Wartick, S. L. (2003). Dealing with stakeholders: How reputation, credibility and framing influence the game. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(1): 19–35. Maneesriwongul, W. & Dixon, JK (2004). Methodological issues in nursing 0 Instrument translation processes: a methods review. Journal of Advanced Nursing 48(2): 175–186 Matthews, P & Sammons, P (2004). Improvement through Inspection: An evaluation of the impact of Ofsted’s work, London: Ofsted/Institute of Education. Mulford, W., Silins, H. & Leithwood, K. (2004). Educational Leadership for Organisational Learning and Improved Student Outcomes. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Morken, H. & Formicola, J.R. (1999). The politics of school choice. Maryland: Rowman and Littlefield Inc Nguyen, N. & LeBlanch, G. (2001). Image and reputation of higher education institutions in student’s retention decisions. The International Journal of Educational Management, 15(6): 303-311. Spaull, N. (2013). South Africa’s Education Crisis: The quality of education in South Africa 1994-2011. Johannesburg: Centre for Development and Enterprise. Scheerens, J. (2004). Review of school and instructional effectiveness research. Background paper prepared for the Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2005. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. Scholes, E. & Clutterbuck, D. (1998). Communication with stakeholders: an integrated approach, Long Range Planning, 31(2): 227-238. Shapiro, C. (1982). Consumer information, product quality, and seller reputation. The Bell Journal of Economics, 13:20-35. Vidal, P. & Torres, D. (2005). The social responsibility of Non Profit Organisations: a conceptual approach and development of SRO model. Barcelona: Observatori del Tercer Sector. Wartick, S.L. (1992). The relationship between intense media exposure and change in institutional reputation. Business and Society, 31: 33-49. 1447