6 CRITICAL THEORIES Marxist, Conflict, and Feminist

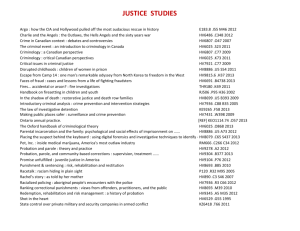

advertisement