An Investigation of Cultural Cohesion and Bryce M, Payne Oregon State University

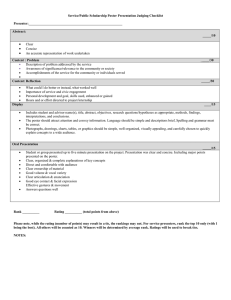

advertisement