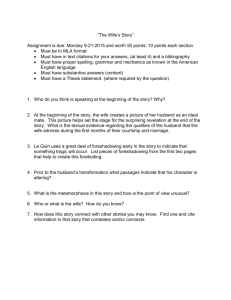

Jaspal K Singh for the degree of Master of Arts... English, English, and Women Studies presented on May 28, 1993.

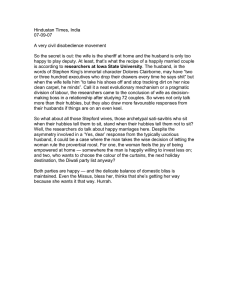

advertisement