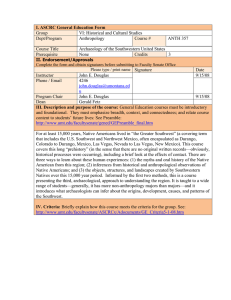

I. ASCRC General Education Form Group X: Indigenous and Global Perspectives Dept/Program

advertisement

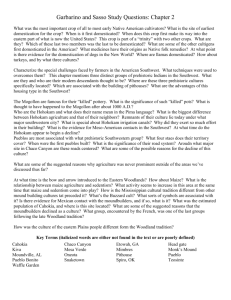

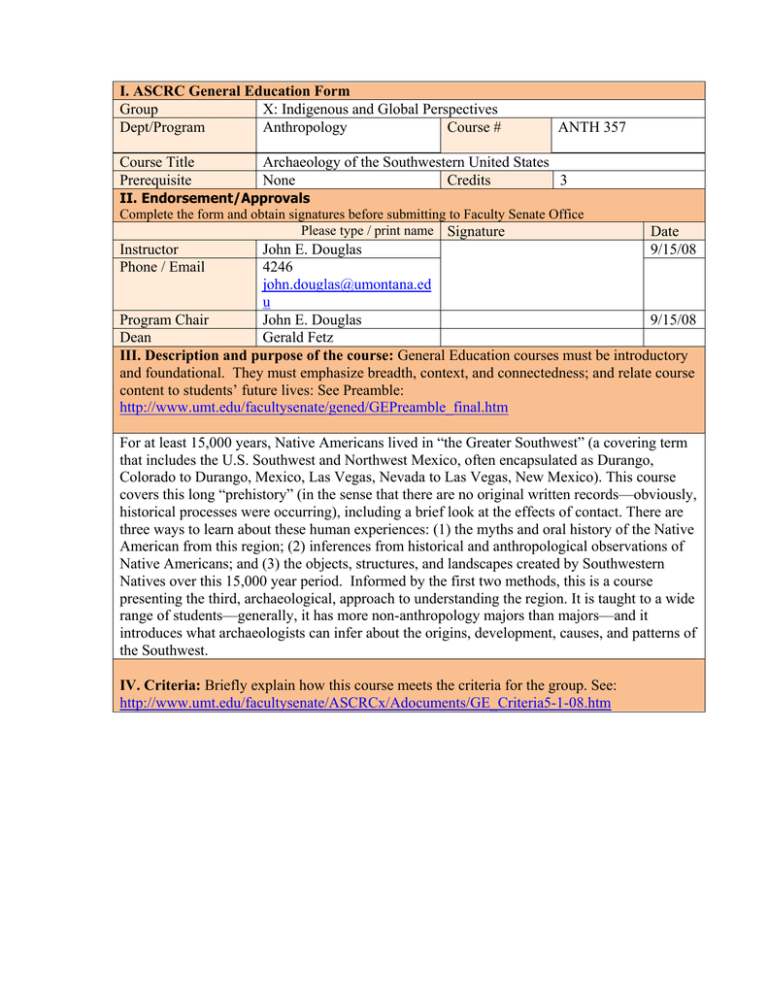

I. ASCRC General Education Form Group X: Indigenous and Global Perspectives Dept/Program Anthropology Course # Course Title Prerequisite ANTH 357 Archaeology of the Southwestern United States None Credits 3 II. Endorsement/Approvals Complete the form and obtain signatures before submitting to Faculty Senate Office Please type / print name Signature Date John E. Douglas 9/15/08 4246 john.douglas@umontana.ed u Program Chair John E. Douglas 9/15/08 Dean Gerald Fetz III. Description and purpose of the course: General Education courses must be introductory and foundational. They must emphasize breadth, context, and connectedness; and relate course content to students’ future lives: See Preamble: http://www.umt.edu/facultysenate/gened/GEPreamble_final.htm Instructor Phone / Email For at least 15,000 years, Native Americans lived in “the Greater Southwest” (a covering term that includes the U.S. Southwest and Northwest Mexico, often encapsulated as Durango, Colorado to Durango, Mexico, Las Vegas, Nevada to Las Vegas, New Mexico). This course covers this long “prehistory” (in the sense that there are no original written records—obviously, historical processes were occurring), including a brief look at the effects of contact. There are three ways to learn about these human experiences: (1) the myths and oral history of the Native American from this region; (2) inferences from historical and anthropological observations of Native Americans; and (3) the objects, structures, and landscapes created by Southwestern Natives over this 15,000 year period. Informed by the first two methods, this is a course presenting the third, archaeological, approach to understanding the region. It is taught to a wide range of students—generally, it has more non-anthropology majors than majors—and it introduces what archaeologists can infer about the origins, development, causes, and patterns of the Southwest. IV. Criteria: Briefly explain how this course meets the criteria for the group. See: http://www.umt.edu/facultysenate/ASCRCx/Adocuments/GE_Criteria5-1-08.htm Indigenous and/or global courses will familiarize students with the values, histories, and institutions of two or more societies through the uses of comparative approaches. Indigenous perspective courses address the longstanding tenure of a particular people in a particular geographical region, their histories, cultures, and ways of living as well as their interaction with other groups, indigenous and non-indigenous. Global perspective courses adopt a broad focus with respect to time, place, and subject matter and one that is transnational and/or multicultural/ethnic in nature. Whether the cultures or societies under study are primarily historical or contemporary, courses investigate significant linkages or interactions that range across time and space. By examining “the Greater Southwest” from the first “peopling” up to the historic period, students gain a sense of how Native American institutions originate, evolve and change. The class is inherently comparative in two senses. First, it examines a range of Native American cultures (Hohokam, Anasazi, Mogollon, Salado, to use some of the more familiar names)—from the apparently ritual-based “great houses” of Chaco Canyon region of northwest New Mexico, to the highly diverse adaptations in the Mogollon highlands, to the canal-based towns of the Hohokam in the Phoenix Basin. It also considers one of the great questions of the Southwest: to what extent is it merely derivative of the “Great Tradition” of Mesoamerica to the south? In examining that issue, the issue of local innovation and determination versus “international” style and organization can be examined in a world very different than our own. Finally, the class examines contact with Europeans— albeit briefly, given the lengthy prehistoric sequence that is presented—so that essential contrasts with European societies are also made. The course has an indigenous perspective. Archaeology offers a unique view: Native American culture without the effects of the European expansion. That is not to say eurocentric ideas do not influence our interpretation— those problems with archaeology are dealt with explicitly— but the record itself represents a unique window on Native America. V. Student Learning Goals: Briefly explain how this course will meet the applicable learning goals. See: http://www.umt.edu/facultysenate/ASCRCx/Adocuments/GE_Criteria5-1-08.htm Most of the course is organized into a time Place human behavior and cultural ideas into a wider (global/indigenous) framework, and and space grid: culture “areas” (groups enhance their understanding of the complex related by shared heritage and adaptations) interdependence of nations and societies and are introduced, then the changes and their physical environments. innovations in the area examined through time. Thus, there is a strong sense of local development. The course also provides specific comparisons between these areas, in order to show differences, similarities, trends and contacts that knit together the Greater Southwest. “Hinge-points” and critical issues in the prehistoric record are explored in detail. What conditions lead to the adoption of agriculture? What are the social conditions that lead to social ranking? These kinds of questions (see the syllabus) are dealt within specific historical contexts and narratives. A tool that I use to get students to take an Demonstrate an awareness of the diverse ways humans structure their social, political, and indigenous view is to ask them to write a cultural lives. short piece of “historic fiction,” accurately placing a story they invent in the past we’re studying. No doubt, I get my share of turgid dialog and ill-advised assumptions about people who were very different than 21st century Americans. However, student enthusiasm for the project, and the platform the exercise provides to really get at the differences between “us” and people in this prehistoric past, has made this a very useful exercise in my class. This class is often an eye-opener for Analyze and compare the rights and responsibilities of citizenship in the 21st century students and inherently comparative to “western civilization” for students, because including those of their own societies and cultures. of the echoes of the Victorian–era view that placed Europeans at the pinnacle of human existence that is still present in popular culture. Few students have any idea that the prehistoric Southwestern Indians had such sophisticated agricultural systems, substantial towns, or involved religious and ritual systems. Simplistic notions of EuroAmerican “progress” are challenged by this class. VII. Syllabus: Paste syllabus below or attach and send digital copy with form. ⇓ The syllabus should clearly describe how the above criteria are satisfied. For assistance on syllabus preparation see: http://teaching.berkeley.edu/bgd/syllabus.html ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE SOUTHWESTERN U.S. (Anthro 357) 2008 Wintersession Professor: John Douglas; Office: Social Sciences 233; E-mail: John.Douglas@umontana.edu; Tel: 243-4246; Office hours: M-Th 11-12, or appointments welcome. Description: In this course, we will discuss the prehistoric people of the American Southwest and the Mexican Northwest, including significant changes in subsistence, technology, social systems, and political organization between 9200 B.C., the earliest established date for human occupation, and A.D. 1540, when Spanish contact began producing major changes. We will gain an appreciation of the adaptations of the peoples of the Southwest to an often harsh environment, with a particular focus on how agricultural communities functioned. Furthermore, by studying the prehistory of the Southwest, we also will learn more about the methods that archaeologists use to understand the past. Prerequisites: None Required text: Plog, Stephen, 1997, Ancient Peoples of the American Southwest, Thames and Hudson, New York. The book is available in the bookstore. Suzanne K. Fish, Paul R. Fish, and John H. Madsen, Editors, 1992, The Marana Community in the Hohokam World, Anthropological Papers of the University of Arizona, number 56. A complete online version of the Fish et al. monograph is available for free is available at: http://www.uapress.arizona.edu/onlinebks/Fish/contents.htm. Tests: There are two tests. Each test is worth 100 points. A test follows each unit and covers the unit's lecture material and assigned readings (the last one falls on the last day). Test questions include multiple-choice, true-false, and matching, and short definition. Papers: Besides the tests, undergraduates must prepare an assignment to research and write a brief story or scene set in the prehistoric Southwest. The details of this assignment are outline at the end of this syllabus. The assignment is worth 100 points. Any graduate student taking the class must talk to me about an alternative assignment. Extra Credit Assignment: You can earn up to 15 points (5% of your grade) by giving a 10 minute PowerPoint presentation to the class on the last day. See instructions at the end of the syllubus. Grade Determination: There are 300 points possible in the class (400 for grad students); students with 90% or more of the possible points will receive an "A," etc. (see below). Grade Points A B C D (or “credit”) 270 + 230+ 200+ 170+ Other issues: Plagiarism and misconduct: All students must practice academic honesty. Students unfamiliar with the Plagiarism Warning in the catalog are urged to read it. Plagiarism and Academic misconduct is subject to an academic penalty by the instructor and/or a disciplinary sanction by the University. All students need to be familiar with the Student Conduct Code. The Code is available for review online at www.umt.edu/SA/VPSA/index.cfm/page/1321. Students caught breaking the code will be subject to penalties, up to failing the course and being reported to the Dean of Students. A plea to the wireless crowd: Please turn off you cell phone ringer during class! Disability Accommodations: When requested by the student, learning disabilities recognized by Disability Student Services (DSS) will be ameliorated with any reasonable accommodation: copies of notes, special testing environment, extended testing time, and special forms of the tests. Incompletes: An incomplete will be considered only when requested by the student. At the discretion of the instructor, incompletes are given to students who missed a portion of the class because of documented serious health or personal problem during the semester. Students have one year to complete the course; requirements are negotiated on a case-by-case basis. Class Schedule DAT E TOPIC The Natural Environment/ Native peoples History of Archaeological Research/Methods 2-Jan W 3-Jan Th 4-Jan F Paleoindians in the Southwest/Archaic 7-Jan M Agriculture, Villages, and Ceramics 8-Jan T Hohokam and Patayan 9-Jan 10Jan W The Mogollon-Mimbres Th Midterm READINGS Preface & C. 1. Introduction: People and Landscape C. 2. Paleoindians: Early Hunters and Gatherers C. 3. The Archaic: Questions of Continuity & Change C. 4. The rise of village life, 200 B.C. to A.D. 700 C. 5. From village to town: Hohokam, Mogollon, & Anasazi, 71-93; Fish, Fish and Madsen, Chapters 1-6 11Jan 14Jan 15Jan 16Jan 17Jan 18Jan C. 5. From village to town: Hohokam, Mogollon, & Anasazi, 93-117 F Anasazi/ Chaco Canyon M The Mogollon-Mimbres T Cliff Dwellings and Reorganization C. 6. Cliff Dwellings, Cooperation, and Conflict W Paquime and Northern Mexico (Papers Due) Th Classic Hohokam/transition to history Fish, Fish and Madsen, Chapters 7-9 F Final and Optional Presentations Southwest Archaeology Assignment: Historical Fiction Purpose: This assignment allows you to think more about the lives of people in the prehistoric Greater Southwest by writing a short piece of historical fiction (see Wikipedia discussion of the historic novel/fiction at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historical_fiction for a definition and history). Resources: Like any historic fiction, your story should be framed by what scholarship knows about the time and place; you are then free to imagine the interactions and daily life that remains “hazy” from the archaeological record. Your first task is to understand the archaeology record for the time and place you have defined, and you should use your texts and lecture notes as the basis for this, supplemented by appropriate web and library resources. If you are looking for inspiration for your work, take a glance through Adolf Bandelier’s 1890 novel The Delight Makers. An important early southwestern archaeologist, Bandelier took the unusual step of writing a novel set in the ruins he had excavated in northern New Mexico. The writing is certainly florid as only 19th century fiction authors can be, and it certainly reflects the biases of the time, but nevertheless can be read as an honest attempt to “make the past live.” Still in print, the book is on reserve and is also available from several internet sources; I recommend the Project Gutenberg’s HTML version, which includes the original illustrations (http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/18310). Research: You should read and cite at least three relevant references, besides the course notes and textbooks. At least one must not be an HTML page (eBooks and eJournals are fine). Do not put citations in the story. Instead, list them at the end of the story in any convenient, consistent, format (this is not included in the page count); the standard archaeological format can be found at http://www.saa.org/publications/StyleGuide/styFrame.html. . Assignment: Your vignette/short story should be 4-8 pages of double-spaced text with normal fonts and margins (1,000 to 2,000 words). It should be clear where and when your story takes place; if this is not woven into the story, add an opening paragraph that sets the stage, along the lines of the original “Star Wars” scroll that sets the “back story” for that movie. It is OK to use names of sites and artifacts employed by archaeologists, even though names like “Snaketown,” “Ventana Cave,” or “Clovis Point” are entirely modern. Try to weave a story about how people’s lives in the past were organized on a day-to-day level (I will not look kindly on stories focused solely on “great leaders” or “great warriors;” I will be even harsher on stories focused on alien landings, etc.) Grading: Roughly 50% of the grade will be based on the amount, accuracy, and relevance of the archaeological information that you employ; 30% on your creativity in weaving a story that helps bring daily life of people alive, and 20% on grammar, spelling, and punctuation. Southwest Extra Credit Assignment: Class Site Presentation (15 points) General Instructions: • Choose a site that interests you and there are research materials available. • • • • Obviously, images on the internet will make this assignment easier, but you can scan images from a book or clip them from eBooks or eJournals. Choose a specific place that people lived or did other activities: Mug House, not Mesa Verde, Fajada Butte, not Chaco Canyon. Sign up with me about your site choice as soon as possible. There will be only one person for each site, on a first come basis. Prepare a PowerPoint presentation on the site with approximately eight slides. You may want to make sure that all your images are sized to make it easy to use by going to the “format picture” controls, then the “Picture” Tab, then the “Compress . . “button, then make sure “all pictures” in the document checkbox, then compress, followed by clicking OK. Turn in a copy of your PowerPoint presentation with a title that includes your last name to me at Blackboard (http://courseware.umt.edu) by 10 am on January 18 using the digital dropbox. I’ll load your presentation on my computer and you will give a 10 minute talk about your site on January 18. Check List of Suggestions and Requirements: • • • • • • Your first slide should be a title page with the site name and your name The second slide must be a general site of the region showing the site location Normally, you should include a site map The Notes section of PowerPoint should give the reference for any figures on that slide The last slide should have your bibliography. Use a standard scheme, such as http://www.saa.org/publications/StyleGuide/styFrame.html Provide basic information about the site, including o Dates Culture that occupied it Environmental setting Function or activities found at the site What makes the site interesting If relevant, include names of excavators, controversies, preservation issues, etc. • Keep your writing to a minimum; bullet major talking points • Use your research skills to find accurate, scientific, and archaeological sources. If you have questions, ask me. • Don’t present other people’s writing as your own! I will hold you to the Student Code of Conduct, and if honesty isn’t its own reward, consider how easily the Internet is searchable and that this is my area of specialty, so be warned! *Please note: As an instructor of a general education course, you will be expected to provide sample assessment items and corresponding responses to the Assessment Advisory Committee. o o o o o