“I” on the Web: Social Penetration Theory Revisited

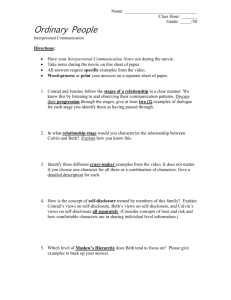

advertisement