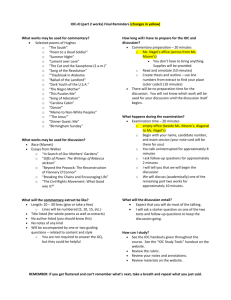

INFORMATION DOCUMENT

advertisement