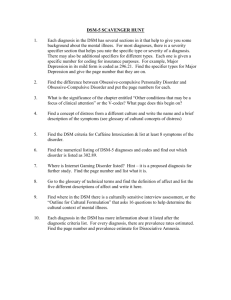

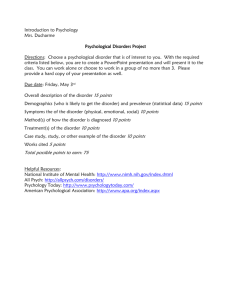

Workshop ObjecLves DSM‐5 March 25, 2015 The DSM‐5:

advertisement