29 Best Practices in the Analysis of Progress-Monitoring Data and Decision Making

advertisement

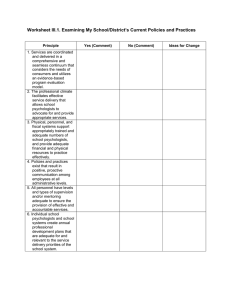

29 Best Practices in the Analysis of Progress-Monitoring Data and Decision Making This is a pre-print. I apologize if there are some errors. This now published in Best Practices VI. OVERVIEW Progress monitoring is one of the most important tools used by school psychologists to evaluate student response to both academic and behavioral interventions. It is the basis for data-based decision making within a multitiered problem-solving model and it solidifies the linkage between assessment and intervention. Research and program evaluation is a foundation of service delivery in the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP) Model for Comprehensive and Integrated Psychological Services (NASP, 2010). Progress monitoring is essential in ensuring that student outcomes are tightly linked with services and programs provided within schools. By providing a real-time account of how interventions are effectively (or not effectively) moving students toward predetermined goals, it helps to ensure accountability for school personnel and adds a selfcorrecting feature to intervention efforts. Within a multitiered system, evaluation of student progress within tiers and movement between tiers highly depends on careful and accurate evaluation of student performance over time. This chapter provides general guidelines for school psychologists for selecting and measuring student behavior, displaying and analyzing ongoing data, and making decisions based on progress-monitoring data. After reading this chapter, school psychologists will be aware of issues related to selecting valid and reliable Michael D. Hixson Central Michigan University Theodore J. Christ University of Minnesota Teryn Bruni Central Michigan University measures of student behavior, they will be able to analyze characteristics of graphic displays, and they will be able to apply decision guidelines to determine the effectiveness of interventions. BASIC CONSIDERATIONS In the 1920s and 1930s, B. F. Skinner took repeated measures of individual rats to determine the effects of various environmental manipulations on the frequency of lever pressing. His simple experimental arrangement uncovered the basic principles of behavior and learning. The methods he used were adapted in the 1950s and 1960s to study human behavior. It is a version of those methods of single-case design that are used for progress monitoring in schools. The term, but not the concept, of progress monitoring emerged alongside curriculum-based measurement (CBM) and problem solving, but it is used today in school psychology to reference practices with a variety of measurement methods and domains of behavior. Progress monitoring is a hallmark feature of problem solving within a multitiered service delivery model. By measuring behavior over time and observing how changes in the environment have an impact on that behavior, school psychologists can make more informed instructional decisions to improve student outcomes. Instructional time is not wasted on ineffective interventions and specific variables affecting behavior can be 1 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology systematically tested and monitored (e.g., Batsche et al., 2005; Stecker, Fuchs, & Fuchs, 2005). One of the most commonly used systems to measure academic progress is CBM. Although progress monitoring using CBM is recommended in the professional literature, the research basis of CBM for progress monitoring is limited, as demonstrated in four publications. First, the report on multitiered services in reading, which was developed by an expert panel convened by the Institute for Educational Sciences in the U.S. Department of Education, found that CBM reading progress monitoring does not result in improved student outcomes. Specifically, the expert panel stated: Of the 11 randomized controlled trials and quasiexperimental design studies that evaluated effects of Tier 2 interventions and that met WWC [What Works Clearinghouse] standards or that met WWC standards with reservations, only 3 reported using mastery checks or progress monitoring in instructional decision making. None of the studies demonstrate[s] that progress monitoring is essential in Tier 2 instruction. However, in the opinion of the panel, awareness of Tier 2 student progress is essential for understanding whether Tier 2 is helping the students and whether modifications are needed. (Gersten, 2009, p. 24) Second, in their review of the literature, Stecker et al. (2005) concluded that CBM was often ineffective because educators do not implement the procedures with fidelity and they often fail to respond to the data. Third, in another review of the literature, Ardoin, Christ, Cormier, and Klingbeil (2013) concluded that there was poor to moderate support for the frequently reported guidelines associated with progress monitoring using CBM. Neither the guidelines for progressmonitoring duration, such as the number of baseline data points to collect, nor the corresponding decision rules were well supported in the literature. Finally, a number of published studies refute the notion that CBM oral reading fluency progress monitoring is reliable, valid, and accurate when the duration of monitoring is short, procedures are poorly standardized, or instrumentation is of poor quality (Christ, 2006; Christ, Zopluoglu, Long, & Monaghen, 2012; Christ, Zopluoglu, Monaghen, & Van Norman, 2013). Although the research literature on using CBM for progress monitoring is limited, there has been a large body of basic and applied research using direct measures of behavior for progress monitoring. School psycholo2 gists need to carefully consider a number of variables when designing progress-monitoring measures. BEST PRACTICES IN THE ANALYSIS OF PROGRESS-MONITORING DATA AND DECISION MAKING The following sections describe best practices for school psychologists for collecting and graphically displaying progress-monitoring data, for analyzing data, and for making decisions based on progress-monitoring data. These activities fall within the area of formative evaluation, which is a key component of the problemsolving model. Formative evaluation of progress monitoring data most commonly occurs within Tiers 2 and 3 of a multitiered system of service delivery. Although there is a large research literature in behavior analysis that has used what could be reasonably referred to as progress-monitoring data as the primary dependent variable, the research on certain types of data for progress monitoring is still evolving. Therefore, specific best practice guidelines are not always possible. Rather, school psychologists need to be aware of the issues related to interpreting and analyzing progress-monitoring data. Best Practices in Data Collection and Data Display Identifying a valid and reliable behavior for progress monitoring is challenging. This section presents a summary of best practices for school psychologists for data collection and data display and discusses issues related to selecting valid and reliable progress-monitoring measures. Validity and Reliability of ProgressMonitoring Data School psychologists must use valid measures of behavior. Validity refers to whether the assessment instrument measures what it purports to measure. The first step in developing a valid progress-monitoring measure is to define the behavior in observable terms. It is often quite difficult to turn teacher and parent concerns into objective definitions of behavior. In order to have a direct measure of the behavior, the behavior should have a clear beginning and end and the conditions under which the behavior occur should be identified. The behavior measured should be the same as the one in which conclusions will be drawn (Johnston National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Progress Monitoring & Pennypacker, 2009). For example, if the student frequently does not follow teacher directions, then this behavior can be directly measured by recording the number of instances of noncompliance and dividing it by the number of teacher directions. An indirect measure of the behavior would be the completion of a behavior rating scale by the teacher that measured student compliance. This is indirect because teacher behavior is measured but school psychologists are interested in student behavior. When the appropriate dimension of the behavior of concern is directly measured, then the measure is a valid one. As another example, if the concern is accuracy in solving addition problems, then the number of correct and incorrect problems can be recorded from the student’s independent practice worksheets. If accuracy with solving math problems was the concern but duration of solving the math worksheets was recorded, then the measure would be indirect and invalid. In addition to directly measuring the appropriate dimension of behavior, the measurement should take place at the appropriate time and place. Student performance can only be understood within a given environmental context. If a student’s noncompliance occurs in academic subjects but not during other activities, such as gym class and recess, then the behavior should be measured during the academic subjects. Ideally, all instances of the target behavior are recorded (this is called continuous recording), but if the behavior is only sampled then the issue of whether a representative or valid sample was obtained becomes a concern. Direct measures of specific behaviors provide valid and accurate accounts of behavior and are preferred over indirect measures, particularly when providing more targeted or intensive interventions. Indirect measures are often convenient to obtain, but school psychologists should always be concerned with validity. The validity of indirect measures may be obtained by correlating scores on the indirect measures with scores on a direct measure. Measuring behavior using curriculum materials for progress monitoring can be considered direct or indirect measures of behavior depending on how precisely they correspond with the behavior of interest. For example, if the behavior of interest is reading rate and CBM Reading is derived from curriculum materials or closely related materials, then there is a direct measure of the target behavior, which is reading rate. But if the same CBM passages are used as a general outcome measure of reading (i.e., to assess the broader skill of reading or general reading achievement), then the broad behavior of reading is being indirectly measured. CBM reading and reading rate are only indicators of reading, which is composed of many behaviors. Because general outcome measures are used as indicators of a broader skill set, validity and reliability must first be demonstrated to support their use as formative measures of student progress. Fortunately, a large amount of reliability and validity research supports the use of CBM reading for screening. However, data collected from broad measures that sample skills, such as CBM Reading, tend to be highly variable when used for progress monitoring. A reliable measure is one in which the same value is obtained under similar conditions. With indirect measures, traditional psychometric reliability procedures are used to determine the reliability of the measure, such as administering the test two times under the same conditions and correlating the scores in test-retest reliability. Because progress-monitoring measures are often direct measures of behavior or behavior products, the most relevant type of reliability measure is interrater reliability or interobserver agreement. School psychologists should collect interobserver agreement data when there is concern about the reliability of the data or when the data are used to make important decisions. Interobserver agreement is calculated from the data from two observers who have measured the same behavior at the same time. There are various methods to collect interobserver agreement data, some of which depend on the type of data that have been collected. If the data recorded were the number of call-outs in class, one observer might have recorded 8 instances of the behavior and the other 10 instances. With this type of frequency data, interobserver agreement is typically calculated by dividing the smaller number by the larger and multiplying by 100%, in this case yielding 80% interobserver agreement. The same calculation is used with duration data; that is, the smaller duration is divided by the larger duration. This calculation is sometimes referred to as overall agreement or total percent agreement. With interval data, trial data, or permanent product data, the calculation can be based on each instance of agreement or disagreement. This type of interobserver agreement is sometimes called point-by-point agreement. If interval data were collected, then the data from each interval are compared across observers and the number of intervals in which there were agreements is divided by the number of agreements plus disagreements. The results are multiplied by 100% to yield the percentage of intervals in which the observers agreed. The same approach to Foundations, Ch. 29 3 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology calculating interobserver agreement can be used with trial-by-trial data by substituting intervals with trials. Parallel Measurements and Variability Progress monitoring requires measurements that are approximately parallel across time. That is, the measurement conditions must be consistent so that data are comparable. Thus, school psychologists should conduct observations of classroom behavior while controlling for time of day, activity, educators, and other potentially influential factors. Ensuring parallel measurement conditions allows us to maximize the potential to observe true intervention effects. Christ et al. (2013) engaged in extensive and systematic research to evaluate the effects of assessment conditions on CBM Reading progress-monitoring outcomes, and these general findings may apply to some other progress-monitoring measures. In the case of academic assessment and CBM, alternate forms must be approximately parallel, which means that content and difficulty of alternate forms should be very similar. As with any progress-monitoring measure, the other conditions of assessment must also be standardized, such as time of day, administrator, and setting. Display of Progress-Monitoring Data Once the relevant dimension of behavior is identified and accurate, reliable, parallel, and valid measures of performance are selected, school psychologists must decide how to present data so that changes in performance over time can be effectively interpreted and evaluated. Progress-monitoring data are displayed graphically and interpreted through methods of visual analysis. Graphic displays of data are useful because they provide a clear presentation of behavior change over time and allow for quick and easy interpretation of many different sources of information. Accurate interpretation and analysis of data depends highly on how it is displayed and organized. There are many formats that school psychologists can use to display data including bar graphs, scatterplots, and tables. The most common progress-monitoring format is the line graph. Line graphs are useful because they facilitate visual analysis with or without supplemental graphic or statistical aides. Graphical aides include goal lines, trendlines, level lines, and envelopes of variability. Statistical aides include estimates of the average level or slope of the trendline of behavior across observations. Graphs typically include data points, data paths, phase changes (i.e., alternate conditions), and axes. Figure 29.1 presents each component using hypothetical data. The lower horizontal axis corresponds with the time variable, which is often measured in days or weeks. The units along the horizontal axis should be depicted in a manner that preserves that unit of time, rather than a scale that indicates session numbers or observation intervals that do not indicate how much time passed Figure 29.1. Basic Components of a Line Graph 4 National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Progress Monitoring between measurements. The time metric is required to accurately represent changes in student performance and to calculate trend. The vertical axis corresponds with the measurement variable (i.e., the outcome) being measured, such as the number of words read correctly per minute. The scale used for the dependent variable will depend on the student’s current level of performance, expected gains over time, and the overall goal of the intervention. Performance is then measured repeatedly over time within the different conditions or phases. Data points are typically represented by small symbols such as open circles, triangles, or squares. Each symbol depicts a data series or outcome measure. The symbols are placed on the graph to represent performance at specific points in time. The lines that connect each data point are called the data path. Data paths connect data points within a condition. New conditions are depicted by solid vertical lines that correspond to a point in time. As shown on the sample graph in Figure 29.1, it is also useful to insert a text box above the graph that defines relevant information about the student (e.g., name, teacher, grade, year), specific measurement procedures, intervention conditions, and a clearly stated measurable objective/goal for the student. Milestones that define intermediate goals (e.g., monthly, quarterly) are often helpful. Such information communicates the purpose, features, goals, and subject of the graphic display, which is useful as an archival record and for purposes of sharing the data with others who might be less familiar with the case. Specific best practices and conventions to construct line graphs exist within the single-case design literature to facilitate interpretation and analysis that can help guide school psychologists in constructing clear and useful graphs to monitor student progress (Cooper, Heron, & Heward, 2007; Gast, 2010; Riley-Tillman & Burns, 2009). First, clarity can be impeded by including more than three behaviors on a single graph (Gast, 2010). If multiple behaviors are represented on the same graphic display, then each behavior should be related to one another to provide meaningful comparisons between the data series (e.g., behavior to decrease presented with the corresponding replacement behavior). Also, trendlines and data paths are disconnected between phase changes, extended gaps in data collection, and follow-up data collections. Finally, school psychologists should ensure that the scales used accurately represent the outcome being measured, including the maximum and minimum values that could be obtained. Each axis should be clearly labeled to indicate the variable of interest, dimension measured (in the case of the vertical axis) and the scale of measurement used (e.g., percent correct on the vertical axis with days on the horizontal axis). Frequency data on the vertical axis are usually displayed with equal intervals; that is, the distance between any two points is always the same. For example, the distance between 3 and 4 words read correctly is the same as between 20 and 21 words on a particular graph. On equal interval graphs, change from one unit to the next across all values of a particular scale is represented by the same distance between each unit. Rather than looking at these absolute changes, school psychologists may also find it useful to look at relative changes in performance. Relative changes can be visually analyzed by using a logarithmic or ratio scaled vertical axis. Although it requires some training and practice initially, it helps to visually analyze the proportional change in behavior. For example, a change from 10 to 20 words read correctly would appear as the same degree of change as from 40 to 80 words because the proportional change is the same; that is, both are doubling over time. Equal interval graphs by necessity use different scales to measure behaviors that differ greatly in their frequency. It is difficult to use a standard nonlogarithmic graph to depict behaviors with very different frequencies, such as one that occurs a few times per day and another that occurs hundreds of times per day. In contrast, it is easy to accomplish this with a logarithmic graph. Figure 29.2 illustrates the difference between equal interval and logarithmically scaled data when two behaviors of very different frequencies are plotted on the same graph. The graph on the left shows relatively stable correct and incorrect responses, but it is more evident on the right graph that errors are increasing. A particular semi-logarithmic graph called the Standard Celeration Chart (Graf & Lindsley, 2002; Pennypacker, Gutierrez & Lindsley, 2003) can display behaviors that occur as infrequently as once per day to as often as 1,000 times per minute. Being able to graph almost any human behavior on the same chart is not only convenient but also makes it easy to compare behaviors across charts. Also, it is often the case that school psychologists are interested in relative/proportional change. A change from talking with peers 20 times per day to 21 times may not be very important, but a change from 0 to 1 could very well be. While a full discussion of the differences between equal interval line graphs and the Standard Celeration Chart falls beyond the scope of this chapter, analysis, interpretation, and communication of student outcomes can be enhanced with the Standard Celeration Chart (Kubina & Yurich, 2012). Foundations, Ch. 29 5 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology Figure 29.2. Hypothetical Student Data Using an Equal Interval Scale Compared to a Semi-Logarithmic Scale Best Practices in Analysis and Decision Making This section presents a summary of best practices in the analysis of progress-monitoring data to guide educational decisions. In order to make important decisions regarding student progress, school psychologists must engage in careful analysis of student data. Accurate analysis of progress-monitoring data involves evaluating data within and across conditions, setting goals, and analyzing intervention effects and variability in the data to guide decision making. Analysis of Progress-Monitoring Data in Baseline Progress-monitoring data are repeatedly collected across time before an intervention is implemented. This preintervention condition is called the baseline condition and the data in this condition are collected to 6 permit a comparison to the intervention data. Baseline data can also help school psychologists determine whether or not the reported problem is a real concern. If the baseline data indicate that the student’s performance is not significantly discrepant from peers, then no intervention is warranted. Baseline data should be collected and charted until a stable pattern of behavior emerges. The characteristics of the data that are considered in determining whether there is a stable pattern of behavior are level, trend, and variability. Level refers to the average performance within a condition. Level is often the characteristic school psychologists are most concerned with; that is, the student may be doing something too often or not enough. To estimate a student’s level of behavior, the mean or median can be calculated and illustrated by a horizontal line on the graph. School psychologists should exercise caution when interpreting level if there is a trend in the data or the data are highly variable National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:02 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Progress Monitoring because level might not be substantially representative of the behavior. Trend refers to systematic increases or decreases in behavior over time. It is often estimated with a trendline, which is a graphical aide, or slope, which is a statistical aide. It may take many data points to get an accurate measure of trend. The addition of a trendline may aid in the analysis of trend. Variability refers to how much a student’s data deviate from the level or trendline. It is often estimated with the standard deviation, range, or the standard error of the estimate (Christ, 2006; Christ et al., 2013). There are many influences of behavior that are beyond the school psychologist’s control that can produce highly variable performance. The academic tasks and other classroom factors vary from day to day as do many factors outside of school. Highly variable data obscure trends and levels and, therefore, hinder interpretation of progress-monitoring data. The sources of variability should be identified and controlled, if possible. The collection of additional baseline data is particularly helpful when the data are variable. There are many kinds of extraneous variables that could be responsible for variable performance, including the measurement system itself. The variability of CBM oral reading fluency tends to be relatively high, as might other measures of very broad skills. School psychologists should ensure a relatively stable baseline is obtained so that effects of the intervention can be accurately interpreted. What is considered stable depends on many factors, such as the type of measure being taken and the extent to which clear experimental control is needed. In most cases, school psychologists should consider the data stable if 80% of the data points fall within 20% of the median line (Gast, 2010). The median rather than the mean is used because the mean is more sensitive to extreme scores. If there is an increasing or decreasing trend in the data, then it is helpful to determine the stability of the data around the trendline using the same criterion: If 80% of the data fall within 20% of the trendline, then the trend may be considered stable. See Figure 29.3. For the data in Figure 29.3 a mean line has been drawn that equals 4.9 responses. The mean or level of these data is not their most important characteristic, however, because of the increasing trend in performance which is summarized by the trendline. A stability envelope (Gast, 2010) has been drawn around the data to determine if the data meet the 80–20% criterion for stability around a trendline. In this case, 77% of the data points fall within 20% of the trendline, which is close to the stability criterion. Attending to the most prominent characteristic of the data—level, trend, or variability—is important for understanding the target behavior and for comparing performance across baseline and intervention conditions. After sufficient and relatively stable baseline data have been gathered, the intervention can be introduced. Analysis of Data Across Conditions Collecting progress-monitoring data and thereby obtaining information on the level, trend, and variability of the target behavior before an intervention is implemented is useful in helping to understand the target behavior and the extent to which the behavior is a problem. If the progress-monitoring data are collected from direct Figure 29.3. Illustration of the 80–20% Stability Rule Foundations, Ch. 29 7 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology observations, then the observer may also identify environmental events that trigger or consequate the behavior, which is helpful for intervention planning because it may give clues to the function of the behavior, as is often done as part of a functional assessment or functional analysis. In addition to these benefits, collecting progress-monitoring data in baseline allows an objective evaluation of the effects of interventions. If sufficient baseline data have been collected to determine the level, trend, and variability of behavior, then this information can be used to predict what is likely to happen if conditions stay the same. If the intervention data are very different from this predicted pattern, then it is possible that the change is due to the intervention. Any three of the data characteristics— level, trend, or variability—may change because of the intervention. School psychologists should consider the following factors when trying to determine if any of the three characteristics changed because of the intervention. First, consider whether there were a sufficient number of data points in each condition to obtain a predictable pattern of behavior under both the baseline and intervention conditions. Second, consider the immediacy of effect or how closely the change in behavior corresponds with the introduction of the intervention. According to Kratochwill et al. (2010), the last three data points from the baseline condition should be compared to the first three data points of the intervention condition to evaluate immediacy. Third, consider the degree of overlap of data points across conditions. If few data points overlap, then the results are more likely the result of the intervention. High variability increases the probability of overlapping data points across conditions, which can obscure the effects of the intervention. The percentage of nonoverlapping data points across conditions may be calculated as a summary statistic of overlap. To help determine the degree of overlapping data points across conditions, an envelope can be drawn around the data in baseline and projected into the intervention condition. In Figure 29.4 there is no overlap in data across conditions with the target behavior rapidly decreasing during the intervention and leveling off at around four responses. The envelope encompasses all of the data in the baseline condition and the lines are drawn horizontally. If there is a clear trend in the data, as in Figure 29.5, then the envelope can be drawn by using the slope obtained from the trendline. The data in Figure 29.5 also show a clear change in trend across conditions and no overlapping data points using the slope of the trendline to extend the data envelope. More advanced statistical procedures may be used to analyze trends and changes in data with certain types of progress-monitoring data. For example, in the case of CBM Reading progress-monitoring data, Christ (2006) and Christ et al. (2013) have advocated for the use of confidence intervals to help guide interpretation, especially if it is used for high-stakes diagnostic and eligibility decisions. CBM progress-monitoring measures have published estimates of the standard error of measurement (e.g., median standard error of measurement for CBM reading is 10; Christ & Silberglitt, 2007). Moreover, regression-based estimates of trend have standard errors that are easily derived with spreadsheet software. The Figure 29.4. Illustration of Data Envelope Showing No Overlap Across Conditions 8 National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Progress Monitoring Figure 29.5. Illustration of Data Envelope Defining a Clear Change in Trend Across Conditions function for MS Excel is ‘‘5STEYX(y-values, x-values).’’ The standard error of the slope (SEb) can be applied in a manner similar to the standard error of measurement. That is, the 68% confidence interval is +/2 SEb and the 95% confidence interval is +/2 1.96 * SEb (see Christ & Coolong-Chaffin, 2007, for a more detailed description). The final factor to consider when trying to determine whether or not an intervention was effective is replication of effect. Replication is one of the most powerful ways to show a functional relationship between an intervention and a target behavior. There are various single-case experimental designs that handle replication differently. The two designs most relevant for the progress monitoring of individual students are the withdrawal and alternating treatments designs. In the most common version of a withdrawal design, a nointervention (i.e., baseline) condition is alternated with an intervention condition. The target behavior is measured repeatedly within each condition. In the alternating treatments design, two conditions, which could be no-intervention and intervention conditions, are rapidly alternated. In a withdrawal design the same condition should have a similar effect across phases. For example, if the behavior were low in the first baseline, then it should also be low when the baseline condition is repeated, and if it were high in the first intervention condition, then it should be high in subsequent intervention conditions. For research purposes, a single-case design should have at least three replications of an effect or, in the case of the alternating treatments design, at least five repetitions of the alternating sequence (e.g., BCBCBCBCBC; Kratochwill et al., 2010). We believe these criteria are also useful for school psychologists when high-stakes decisions need to be made with progress-monitoring data, as is discussed in the next section. Best Practices in Data-Based Decision Making Progress monitoring alone does not produce meaningful gains in student performance. Decisions must also be made based on careful analysis of student data (Stecker et al., 2005). Although there has been research on the use of decision rules, few studies have investigated the effects of specific rules. However research in the areas of single-case designs, CBM, and response to intervention outline important considerations to help guide school psychologists in making decisions based on student data. Student performance data should be evaluated in relation to a specific goal. Goals can be based on local norms, benchmark data, classroom norms, or peer comparisons. Goals are set over a specified amount of time, allowing for short-term objectives to be set regarding the student’s rate of progress (e.g., acquire two letter sounds per week). A student’s expected rate of progress can be represented by an aimline, which is a line drawn from the last or median baseline point to the expected goal (see Figure 29.6). The aimline is used as a guide for determining whether or not the student is making sufficient progress toward the goal. Progress should be evaluated in a manner that takes into consideration all elements related to the students’ environment and should be applied flexibly. The following considerations provide some general rules/ guidelines for decision making that have been used in research on progress monitoring or have been recommended by experts. Foundations, Ch. 29 9 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology Figure 29.6. Expected Rate of Progress Represented by Aimline and Illustration of Trendline Based on Hypothetical Student Data Interpreting Changes in Performance In many cases it may not be vital to determine if it was intervention or some other factor that improved student performance. But as students move through Tiers 2 and 3 and they are given more intensive instruction, it becomes increasingly important to correctly identify controlling variables. If progress-monitoring data are being used to help determine eligibility for special education, then it is of primary importance that an effective intervention is identified (Riley-Tillman & Burns, 2009). If the effective intervention is highly intensive, then it may require special education placement. Knowing that the intervention is in fact responsible for the improvement is necessary because student eligibility for special education is one of the most important decisions school psychologists make. Using an experimental design that involves replication such as a reversal, multiple-baseline, or alternating treatment design provides a powerful demonstration for the necessity of that intervention for student success and greatly increases the reliability of the school psychologist’s decision. Because the use of a rigorous experimental design takes time to implement, it should ideally be done before a request for a special education evaluation because of the evaluation timelines that begin once a referral is made. Variability in data and/or the occasional extreme value can be the result of many factors, as previously discussed. Parallelism should be considered if progressmonitoring data are highly variable. Measurement 10 factors are important to evaluate, such as standardization of conditions, instrumentation, and reliability of scoring. In addition, a possible problem with CBM is nonequivalent probes, which could be evaluated by administering different probes under the same conditions (time, assessor) and calculating differences in scores. Variability may also be due to instructional factors, which include the fidelity of implementation and instructor characteristics (e.g., how fluently the intervention is implemented). Student factors should be examined carefully. These could include biological variables (e.g., student illness), interfering behavior (e.g., noncompliance, failure to scan/attend), or lack of motivation to comply with instructional demands (e.g., insufficient reinforcement for correct responding). If the sources of variability are identified, then they can be controlled to improve the potential for effective, efficient, and accurate decisions. Using Decision Rules There are 40 or more years of recommendations to apply a variety of specific decision rules to progress-monitoring data, which are intended to improve decision accuracy. Student outcomes tend to improve as a function of progress monitoring only if decision rules are explicit and implemented with integrity (Stecker et al., 2005). Two commonly used decision rules are data point rules and trendline rules and neither is supported by substantial evidence (Ardoin et al., 2013). The accuracy of decisions using data point rules has not been researched, but there National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Progress Monitoring has been some research on the trendline rule. The data point rule uses a graphically depicted goal line, which displays the expected growth in performance. If three consecutive points are distributed above and below the goal line, then the intervention is continued, presumably because there is evidence of sufficient progress toward the goal. If three consecutive points are all below the goal line, then the intervention is changed because there is evidence of insufficient progress. Finally, if three consecutive points are all above the goal line, then the goal is increased because there is evidence of an insufficiently ambitious goal. The trendline rule compares an estimate of trend to the intended goal. Prior to the proliferation of computers, the trendline rule was guided by visual analysis or one of a variety of techniques to estimate trend, such as the splitmiddle technique. These estimates of trend should be replaced with statistical methods such as regression (i.e., ordinary least-squares regression). A regression line is the line of best fit to progress-monitoring data, such that it establishes the minimal distance between all points on the trendline and all data points (see Figure 6). Regressionbased estimates of trend are readily available in spreadsheet software and by vendors of many progressmonitoring assessment systems (e.g., Formative Assessment System for Teachers, http://fast.cehd.umn. edu). This method is likely to result in the best estimates of growth and predictions of future performance. However, regression is highly sensitive to extreme values. Visual analysis should be used to identify extreme values. Such values should be judiciously removed from the calculation of the trendline lest they have undue influence on regression-based estimates of trend. That being said, extreme scores may be highly informative if the variables responsible for the extreme score are identified. Overall, decision rules provide school psychologists with a general guide to help evaluate student progress toward a predetermined goal. Accurate and valid measures of behavior, parallel conditions, identifying and controlling for sources of variability, and skills in visual analysis allow school psychologists to make more accurate decisions based on student data. SUMMARY What are the possible consequences of providing an evidence-based treatment in the absence of monitoring the effects of that treatment? Ideally, the treatment would be effective at ameliorating the problem. Unfortunately, school psychologists do not have at their disposal treatments that are 100% effective. Another possibility is that the treatment is ineffective, resulting in wasted time and resources. Finally, the treatment could further impair performance (i.e., have a teratogenic effect). Because of the risk of the second two outcomes, school psychologists are ethically obligated to monitor intervention effects and terminate or change the intervention when appropriate (see Standard 2.2.2 of the NASP Principles for Professional Ethics, http://www. nasponline.org/standards/2010standards/1_ Ethical Principles.pdf). Ongoing progress monitoring is an essential component of data-based decision making within a problemsolving model. School psychologists must first select measures that are reliable, accurate, valid, and sensitive to change. Progress-monitoring data are collected repeatedly over time and plotted graphically to allow for systematic interpretation of results. Level, trend, and variability are three characteristics of progress-monitoring data. Prior to intervention, school psychologists should collect baseline data until sufficient data points permit prediction of the student’s future performance without an intervention. When analyzing data across phases of intervention, school psychologists should carefully inspect the overlap of data points between conditions, the immediacy of change from one condition to the next, and the results from replication of the intervention. Reversal designs, multiple baselines, and alternating treatment designs allow systematic replication and control of independent variables. How systematic school psychologists are in their analysis depends on the types of decisions to be made and the potential impact that decision would have on a particular student. A careful analysis of controlling variables related to instruction, consistency of implementation, setting, and other extraneous variables are necessary when evaluating student progress. REFERENCES Ardoin, S. P., Christ, T. J., Morena, L. S., Cormier, D. C., & Klingbeil, D. A. (2013). A systematic review and summarization of the recommendations and research surrounding curriculum-based measurement of oral reading fluency (CBM-R) decision rules. Journal of School Psychology, 51, 1–18. Batsche, G., Elliott, J., Graden, J. L., Grimes, J., Kovaleski, J. F., Prasse, D., … Tilly, W. D., III. (2005). Response to intervention. Alexandria, VA: National Association of State Directors of Special Education. Christ, T. J. (2006). Short-term estimates of growth using curriculumbased measurement of oral reading fluency: Estimating standard error of the slope to construct confidence intervals. School Psychology Review, 35, 128–133. Foundations, Ch. 29 11 Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003) Best Practices in School Psychology Christ, T., & Coolong-Chaffin, M. (2007). Interpretations of curriculum-based measurement outcomes: Standard error and confidence intervals. School Psychology Forum, 1(2), 75–86. Christ, T. J., & Silberglitt, B. (2007). Estimates of the standard error of measurement for curriculum-based measures of oral reading fluency. School Psychology Review, 36, 130–146. Christ, T. J., Zopluoglu, C., Long, J. D., & Monaghen, B. D. (2012). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading: Quality of progress monitoring outcomes. Exceptional Children, 78, 356–373. Christ, T. J., Zopluoglu, C., Monaghen, B. D., & Van Norman, E. R. (2013). Curriculum-based measurement of oral reading: Multistudy evaluation of schedule, duration, and dataset quality on progress monitoring outcomes. Journal of School Psychology, 51, 19–57. Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (2007). Applied behavior analysis (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. Gast, D. L. (2010). Single subject research methodology in behavioral sciences. New York, NY: Routledge. Gersten, R. M. (2009). Assisting students struggling with reading: Response to intervention and multitier intervention in the primary grades. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. 12 Graf, S., & Lindsley, O. (2002). Standard Celeration Charting 2002. Youngstown, OH: Graf Implements. Johnston, J. M., & Pennypacker, H. S. (2009). Strategies and tactics of behavioral research. New York, NY: Routledge. Kratochwill, T. R., Hitchcock, J., Horner, R. H., Levin, J. R., Odom, S. L., Rindskopf, D. M., & Shadish, W. R. (2010). Single-case designs technical documentation. Washington, DC: Institute of Education Science. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/pdf/wwc_scd.pdf Kubina, R. M., Jr., & Yurich, K. K. (2012). The precision teaching book. Lemont, PA: Greatness Achieved. National Association of School Psychologists. (2010). Model for comprehensive and integrated school psychological services. Bethesda, MD: Author. Retrieved from http://www.nasponline.org/standards/ 2010standards/2_PracticeModel.pdf Pennypacker, H. S., Gutierrez, A., & Lindsley, O. R. (2003). Handbook of the Standard Celeration Chart. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Center for Behavioral Studies. Riley-Tillman, T. C., & Burns, M. K. (2009). Evaluating educational interventions: Single-case design for measuring response to intervention. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Stecker, P. M., Fuchs, L. S., & Fuchs, D. (2005). Using curriculumbased measurement to improve student achievement: Review of research. Psychology in the Schools, 42, 795–819. National Association of School Psychologists Best Practices in School Psychology B4Ch29_W122_Hixson.3d 19/10/13 16:33:03 The Charlesworth Group, Wakefield +44(0)1924 369598 - Rev 7.51n/W (Jan 20 2003)