Reading Codicological Form in John Gower’s Trentham Manuscript Please share

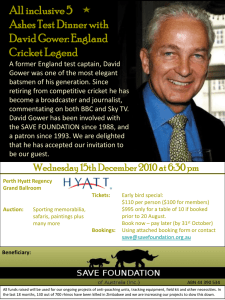

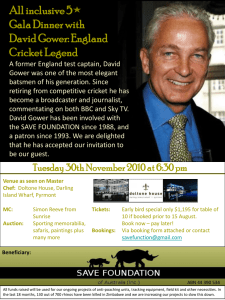

advertisement