Ohio Stackable Certificates: Models for Success February 2008

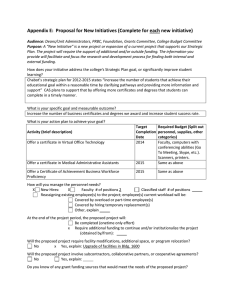

advertisement