BEYOND COLONIZATION—GLOBALIZATION AND THE ESTABLISHMENT OF PROGRAMS OF U.S. LEGAL

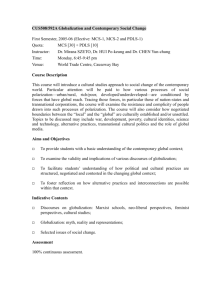

advertisement