Preschool Attendance in Chicago Public Schools Relationships with Learning Outcomes and

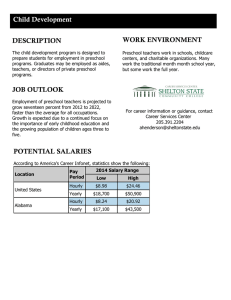

advertisement