Document 11879404

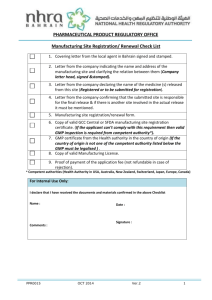

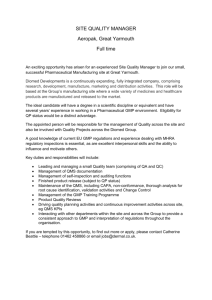

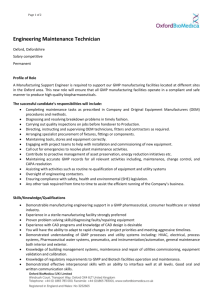

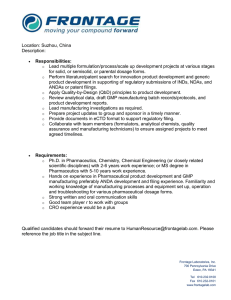

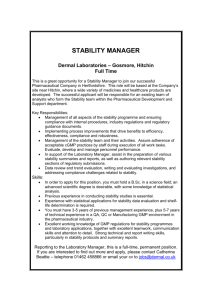

advertisement