Green City Amended

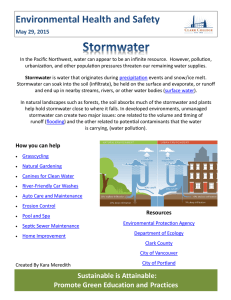

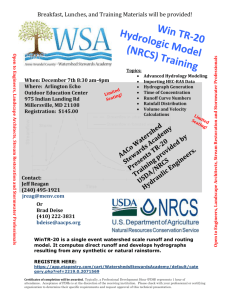

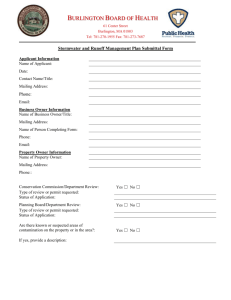

advertisement