Designation of Conservation Planning Units Emily Jo Williams David N. Pashley

advertisement

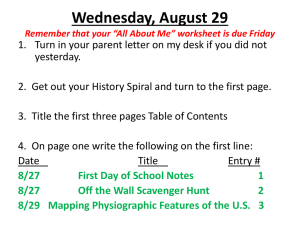

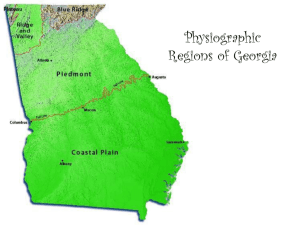

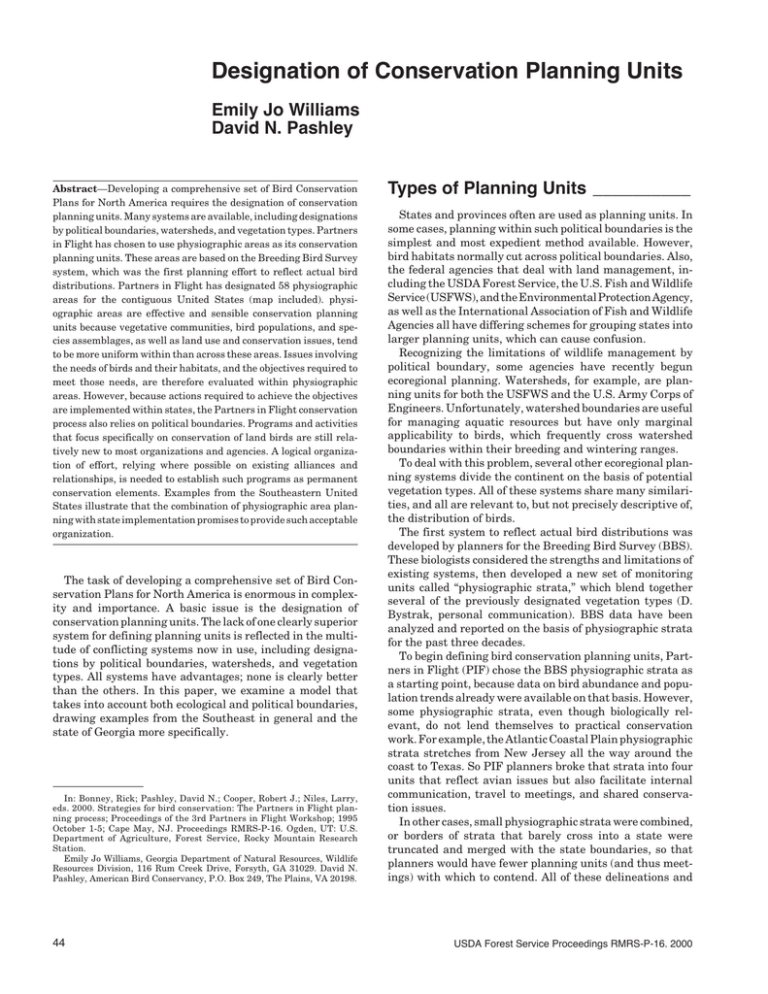

Designation of Conservation Planning Units Emily Jo Williams David N. Pashley Abstract—Developing a comprehensive set of Bird Conservation Plans for North America requires the designation of conservation planning units. Many systems are available, including designations by political boundaries, watersheds, and vegetation types. Partners in Flight has chosen to use physiographic areas as its conservation planning units. These areas are based on the Breeding Bird Survey system, which was the first planning effort to reflect actual bird distributions. Partners in Flight has designated 58 physiographic areas for the contiguous United States (map included). physiographic areas are effective and sensible conservation planning units because vegetative communities, bird populations, and species assemblages, as well as land use and conservation issues, tend to be more uniform within than across these areas. Issues involving the needs of birds and their habitats, and the objectives required to meet those needs, are therefore evaluated within physiographic areas. However, because actions required to achieve the objectives are implemented within states, the Partners in Flight conservation process also relies on political boundaries. Programs and activities that focus specifically on conservation of land birds are still relatively new to most organizations and agencies. A logical organization of effort, relying where possible on existing alliances and relationships, is needed to establish such programs as permanent conservation elements. Examples from the Southeastern United States illustrate that the combination of physiographic area planning with state implementation promises to provide such acceptable organization. The task of developing a comprehensive set of Bird Conservation Plans for North America is enormous in complexity and importance. A basic issue is the designation of conservation planning units. The lack of one clearly superior system for defining planning units is reflected in the multitude of conflicting systems now in use, including designations by political boundaries, watersheds, and vegetation types. All systems have advantages; none is clearly better than the others. In this paper, we examine a model that takes into account both ecological and political boundaries, drawing examples from the Southeast in general and the state of Georgia more specifically. In: Bonney, Rick; Pashley, David N.; Cooper, Robert J.; Niles, Larry, eds. 2000. Strategies for bird conservation: The Partners in Flight planning process; Proceedings of the 3rd Partners in Flight Workshop; 1995 October 1-5; Cape May, NJ. Proceedings RMRS-P-16. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. Emily Jo Williams, Georgia Department of Natural Resources, Wildlife Resources Division, 116 Rum Creek Drive, Forsyth, GA 31029. David N. Pashley, American Bird Conservancy, P.O. Box 249, The Plains, VA 20198. 44 Types of Planning Units __________ States and provinces often are used as planning units. In some cases, planning within such political boundaries is the simplest and most expedient method available. However, bird habitats normally cut across political boundaries. Also, the federal agencies that deal with land management, including the USDA Forest Service, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), and the Environmental Protection Agency, as well as the International Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies all have differing schemes for grouping states into larger planning units, which can cause confusion. Recognizing the limitations of wildlife management by political boundary, some agencies have recently begun ecoregional planning. Watersheds, for example, are planning units for both the USFWS and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Unfortunately, watershed boundaries are useful for managing aquatic resources but have only marginal applicability to birds, which frequently cross watershed boundaries within their breeding and wintering ranges. To deal with this problem, several other ecoregional planning systems divide the continent on the basis of potential vegetation types. All of these systems share many similarities, and all are relevant to, but not precisely descriptive of, the distribution of birds. The first system to reflect actual bird distributions was developed by planners for the Breeding Bird Survey (BBS). These biologists considered the strengths and limitations of existing systems, then developed a new set of monitoring units called “physiographic strata,” which blend together several of the previously designated vegetation types (D. Bystrak, personal communication). BBS data have been analyzed and reported on the basis of physiographic strata for the past three decades. To begin defining bird conservation planning units, Partners in Flight (PIF) chose the BBS physiographic strata as a starting point, because data on bird abundance and population trends already were available on that basis. However, some physiographic strata, even though biologically relevant, do not lend themselves to practical conservation work. For example, the Atlantic Coastal Plain physiographic strata stretches from New Jersey all the way around the coast to Texas. So PIF planners broke that strata into four units that reflect avian issues but also facilitate internal communication, travel to meetings, and shared conservation issues. In other cases, small physiographic strata were combined, or borders of strata that barely cross into a state were truncated and merged with the state boundaries, so that planners would have fewer planning units (and thus meetings) with which to contend. All of these delineations and USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 modifications eventually resulted in a map of the United States that is based upon, but significantly different from, the original BBS physiographic strata map. To stress the difference and reduce confusion between the two, the PIF conservation planning units were named physiographic areas (fig. 1: Note that physiographic area boundaries are agreed upon only for the contiguous 48 states). Utility of Physiographic Areas _____ As an example of how physiographic areas are used, consider the Southeastern Region of PIF. This region encompasses 16 states and all or part of 24 physiographic areas. Some areas are entirely contained within a single state, such as the Edwards Plateau in Texas, whereas other areas cover parts of several states, such as the Mississippi Alluvial Valley. For planning purposes, the evolving Southeastern model takes advantage of both state borders and physiographic area boundaries: The distribution, priority, and needs of birds and habitats—and the objectives required to meet those needs—are evaluated within the physiographic areas, whereas actions required to achieve the objectives are implemented within states. The physiographic area is a sensible conservation planning unit because vegetative communities, bird populations, and species assemblages, as well as land use and conservation issues, tend to be more uniform within than across physiographic areas. As an example, Georgia is a large and diverse state in which the avifaunal and biological issues in an area such as the mountainous Blue Ridge are distinct from, independent of, and difficult to compare with, the avifaunal and biological issues in the South Atlantic Coastal Plain. At the same time, biological issues in Georgia’s South Atlantic Coastal Plain are similar to issues in the South Atlantic Coastal Plain of South Carolina. Therefore, physiographic area boundaries should be used to consider population trends, habitat preferences, and species suites; evaluation of the impacts of management and land-use practices; and the setting of habitat and population objectives. If continental or range-wide objectives exist for a species or a habitat type, then physiographic area objectives should be set within the context of that larger scale. In the absence of larger-scale objectives, the sum of physiographic area conservation objectives for each high-priority bird species should eventually be considered for consistency and sufficiency. In some cases, a species’ potential densities and population sizes are too low within a single physiographic area to provide long-term security for the species. In such cases, conservation objectives must initially be set at the regional level. An example in the Southeast and Georgia is the Swallow-tailed Kite (Elanoides forficatus). The proposed Southeastern goal for this species is the maintenance of at least 80 pairs of kites in each of 13 floodplain forests. Each of these forests should provide about 100,000 acres of habitat suitable for nesting and foraging. Neither Georgia nor the South Atlantic Coastal Plain physiographic area alone can satisfy this goal, but a river system, such as the Altamaha and Savannah, can contribute to the regional objective. Often physiographic area boundaries are similar to the boundaries of other ecologically defined conservation USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 planning units. For example, the PIF Mississippi Alluvial Valley physiographic area roughly coincides with the boundaries of the North American Waterfowl Management Plan Lower Mississippi Valley Joint Venture. The South Atlantic Migratory Bird Initiative is a combined effort within the PIF South Atlantic Coastal Plain physiographic area and the Atlantic Coast Joint Venture. In these and other cases, the United States Shorebird Conservation Plan has developed shorebird objectives within the same geographic boundaries. These schemes provide valuable opportunities for broader partnerships. Planning Relationship Between Physiographic Areas and States ___ Once objectives are set forth in physiographic area conservation plans, the best means of carrying out the objectives is probably on the basis of state or provincial boundaries. The actions of state wildlife agencies will be critical for achievement of many of these conservation objectives: These state agencies tend to have good relationships with many private landowners and corporations whose active and willing participation in PIF is imperative. Also, most federal agencies and private conservation groups are organized on a state basis. In addition, many of the corporations and nongovernmental organizations that own significant amounts of land, or have resources to support conservation action, are organized at least partially by states. At present, each state working group in the Southeast Region is focusing on implementation of the biological objectives defined in the conservation plans for those physiographic areas that extend into the state. These objectives must be combined, balanced, and prioritized within each state. All of the responsibilities for accomplishing conservation actions should be adopted by one or a combination of the partners in the state working group. Examples for which physiographic area objectives are translated into state-level organization abound in Georgia. Portions of five physiographic areas, the South Atlantic Coastal Plain, Southern Piedmont, Southern Blue Ridge, Southern Ridge and Valley, and Cumberland Plateau, extend into this state. Long-term monitoring is a priority conservation action that is being successfully implemented by Georgia’s state PIF working group. The Georgia Wildlife Resources Division (WRD) took the lead in establishing a statewide monitoring system, building upon the extensive U.S. Forest Service system of point counts on the Chattahoochee-Oconee National Forest. Many Georgia WRD biologists and technicians have been trained in bird identification and point-count methodology, along with staff from numerous other organizations including industrial timber corporations, St. Catherines Island Foundation, Little St. Simons Island, USGS Biological Resources Division, Department of Defense (Fort Stewart), and the USFWS. The combined efforts of these many partners have resulted in a statewide monitoring system that covers most of the priority habitats in each of Georgia’s physiographic areas. Monitoring in Georgia has become contagious, and continuing expansions and addition of new partners will ensure that birds in all habitat types in the state will be adequately monitored. 45 Figure 1—Map of Partners in Flight physiographic areas. Key for PIF Physiographic Area Codes 01 Subtropical Florida 02 Peninsular Florida 03 South Atlantic Coastal Plain 04 East Gulf Coastal Plain 05 Mississippi Alluvial Valley 06 Coastal Prairies 07 South Texas Brushlands 08 Oaks and Prairies 09 Southern New England 10 Mid Atlantic Piedmont 11 Southern Piedmont 12 Mid Atlantic Ridge and Valley 13 Southern Ridge and Valley 14 Interior Low Plateaus 15 Lower Great Lakes Plain 16 Upper Great Lakes Plain 17 Northern Ridge and Valley 18 St. Lawrence Plain 19 Ozark-Ouachita Plateau 20 Boreal Hardwood Transition 21 Northern Cumberland Plateau 46 22 Ohio Hills 23 Southern Blue Ridge 24 Allegheny Plateau 25 Open Boreal Forest 26 Adirondack Mountains 27 Northern New England 28 Spruce-Hardwood Forest 29 Closed Boreal Forest 30 Aspen Parklands 31 Prairie Peninsula 32 Dissected Till Plains 33 Osage Plains 34 Central Mixed Grass Prairie 36 Central Shortgrass Prairie 37 Northern Mixed Grass Prairie 38 West River 39 Northern Shortgrass Prairie 40 Northern Tallgrass Prairie 42 West Gulf Coastal Plain 44 Mid Atlantic Coastal Plain 53 Edwards Plateau 54 Rolling Red Plains 55 Pecos and Staked Plains 56 Chihuahuan Desert 62 Southern Rocky Mountains 63 Fraser Plateau 64 Central Rocky Mountains 66 Sierra Nevada 68 Northern Rocky Mountains 69 Utah Mountains 80 Basin and Range 81 Mexican Highlands 82 Sonoran Desert 83 Mohave Desert 84 Mogollon Rim 85 Mesa and Plains 86 Wyoming Basin 87 Colorado Plateau 89 Columbia Plateau 90 Central and Southern California Coast and Valleys 93 Southern Pacific Rainforests USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 It also is advantageous to develop education and outreach materials at a state level. Specific accomplishments in Georgia include a Neotropical migratory bird poster, a teachers’ workshop on Neotropical migrants, and a landowners’ guide to landbird management. Not only is a delivery mechanism for these types of projects lacking on a physiographic area basis, but the materials resonate best to the intended audience within a state context. States that share a physiographic area must communicate in order to assure that their combined efforts meet the needs outlined in the physiographic area plan. Although adding some additional costs such as interstate travel to meetings, multistate efforts foster beneficial communication. The savings in time, effort, and direct expenses realized USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-16. 2000 by this sharing of information and workload more than make up for any additional expenses. In addition, the contribution of each state’s efforts toward broader scale objectives and achievements serves as both impetus and justification for involvement. Programs and activities that focus specifically on conservation of land birds and Neotropical migrants are still relatively new to most organizations and agencies. A logical organization of effort, relying on existing alliances and relationships where possible, is needed to establish such programs as permanent conservation elements. In the Southeast, the combination of physiographic area planning and state implementation promises to provide such acceptable organization. 47