Russian Zapovedniki in 1998: Recent Progress and New Challenges for Russia’s

advertisement

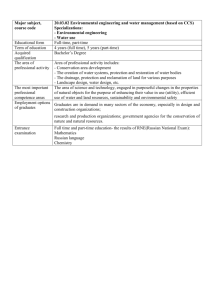

Russian Zapovedniki in 1998: Recent Progress and New Challenges for Russia’s Strict Nature Preserves David Ostergren Evgeny Shvarts Abstract—Zapovedniki are pristine ecosystems that restrict all economic utilization and are designed to act as areas for ecological research and “natural controls” for comparison to other land uses such as agriculture or resource extraction. The most recent threats to zapovedniki originate from the dissolution of the Soviet system and resultant economic instability. Since 1991, zapovedniki have maintained their role in Russian society by increasing contact with international nongovernment organizations, using legislation to increase their ability to enforce the law, expanding environmental education, and diversifying funding strategies. Despite their efforts, the reduction in federal support overrides most efforts to fulfill the mandate of biodiversity conservation, ecological monitoring, and environmental education. Zapovedniki are a unique contribution to the global wilderness community. They are specially protected natural areas that restrict economic utilization or human activity such as logging, mining, farming, hunting, fishing, firewood gathering, or recreation. In theory, zapovedniki are pristine ecosystems designed to act as areas for ecological research and “natural controls” for comparison to other land uses such as agriculture or resource extraction (Kozhevnikov 1908; Shtil’mark 1995; Shtil’mark 1996). The first preserve, Barguzin Zapovednik, was established in 1916 by a regional government to protect a sable population (Martes zibellina) near Lake Baikal. Although several more zapovedniki were established by local and provincial authorities, it was not until 1919 that the first federal zapovednik (Il’menskii Zapovednik) was established (Weiner 1988). This was the first area in the world to be protected primarily for scientific reasons. Since that time, federal, regional, and local government bodies, the Federal Forest Service, or the Russian Academy of Science were authorized to designate ecologically, geologically, or biologically unique or sensitive areas as zapovedniki (Pryde 1991). By the late 1950’s, zapovedniki were established in many ecosystems throughout the Soviet Union. In: Watson, Alan E.; Aplet, Greg H.; Hendee, John C., comps. 2000. Personal, societal, and ecological values of wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress proceedings on research, management, and allocation, volume II; 1998 October 24–29; Bangalore, India. Proc. RMRS-P-14. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. David Ostergren is Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Center for Environmental Sciences and Education, Box 5694, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ 86011U.S.A., e-mail: david.ostergren@nau.edu. Evgeny Shvarts is Professor, Institute of Geography, Russian Academy of Science. He is past Director of the Biodiversity Conservation Center and now with the World Wide Fund for Nature in Moscow, Russia, e-mail: eshvarts@wwfnet.org USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 Threats to Zapovedniki ___________ Throughout the decades, zapovedniki have survived a variety of threats to their operation and existence. The threats have included: • Challenges to the original policies and intent (Shtil’mark 1995; Weiner 1988). • Reductions and reorganizations by political leaders (Boreiko 1993; Boreiko 1994; Pryde 1972). • Alternative use and designation (Pryde 1991). Nonetheless, zapovedniki persevered within the communist, centrally planned economy through 8 decades of shifting prosperity and turmoil. The most recent threats to zapovedniki originate from a more profound source—the complete dissolution of a political system and the associated conditions of economic downturn and social instability (Ostergren 1997; Ostergren and Shvarts 1998; Stepanitski 1997). Until 1991 the zapovedniki were a line item budget for the federal government. Each preserve was allotted money for (1) government inspectors to protect the preserve, (2) scientists to conduct research, (3) support staff, and (4) materials and maintenance. The fall of the Soviet Union changed the way zapovedniki are managed in that directors now spend a significant amount of their time raising funds, nurturing political support, and devising new strategies to do more with less funding. From 1991 to 1995, the zapovednik system struggled to survive under difficult circumstances. Directors at the preserves found themselves with entirely different responsibilities. Because the management lacked sufficient federal funding, government inspectors were paid infrequently or not at all, trespassers poached wildlife for the newly accessible foreign animal parts market, research scientists moved to other jobs to support their families, and essential equipment deteriorated. As one example of a change in support and management techniques, during the Soviet era, helicopter support from the national air service (Aeroflot) was common on established preserves. The Sayano-Shushenskovo Zapovednik was allotted 150 flights to haul supplies to field stations, conduct patrols, and support ground-based inspectors. Of those 150 flights, the scientific staff was allocated 40 helicopter flights a year at the scientific director’s discretion. In 1995, they received five (5) helicopter flights to manage a 390,000 hectare preserve with virtually no road access. These circumstances demand boat transport to the zapovednik and then travel by horse or foot through the preserve. In Central Siberia, zapovedniki with a long tradition of research have cut back on projects and have little or no 209 helicopter support for research or border patrols. New zapovedniki established after 1991 have never had helicopter support (Ostergren 1998). As the funding levels dropped, directors began to turn to alternative techniques for managing preserves. Each director sought outside funding with varying degrees of success from local, regional, and international funding sources. This presentation will provide an update on the challenges, status, and management conditions for zapovedniki in 1998. In particular, we focus on zapovedniki located within Russia. In 1997, despite the challenges in management and a chronic lack of funding, 22 preserves have been added since 1991 for a total of 99 preserves set aside from economic exploitation, protecting over 31,000,000 hectares of diverse ecosystems across Russia. Figure 1 shows the distribution of Russian zapovedniki in 1998. that has been fundamental to progress in advancing protected area status is the Biodiversity Conservation Center (BCC) of the Socio-Ecological Union. The BCC became an advocate for protected areas serving as a consultation, information, and fund-raising center for biodiversity conservation. An excellent source of information on the BCC and related efforts is their web page, http://www.igc.apc.org/bccwest/, or for a more in-depth look at conservation efforts in the 1990’s, the authors suggest referring to the English language publication “Russian Conservation News” (RCN). A subscription for RCN is available through the Pocono Environmental Education Center PEEC/RCN R.R. 2, Box 1010, Dingmans Ferry, PA 18328. In Russian, an excellent source for current information is “Informatsionii Bulletyen” from the “Tsentr Okhrana Dikoi Priroda.” Both literature sources address issues for zapovedniki, as well as national parks and wildlife refuges. Recent Progress for Zapovedniki ____________________ Legislation Shortly after the 1991 fall of the Soviet Union, nongovernment organizations (NGOs) emerged into the political and civil vacuum left by disappearing state committees. In the field of biodiversity conservation and environmental protection, zapovednik directors, natural resource scientists, and environmental activists needed a forum and central source of information to coordinate their efforts. One organization Directors and supportive NGOs requested federal legislation to provide a mandate and legal standing—an “organic act”—for their activities and enforcement (Ostergren 1997; Shtil’mark 1995). In 1995, “The Law on Specially Protected Natural Areas” was passed by the Duma and signed by President Yeltsin. This landmark legislation outlined the legal standing and goals for zapovedniki, including six primary responsibilities: (1) the conservation of Figure 1—Distribution of Russian Protected Areas. 210 USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 biodiversity, (2) the preservation of unique or typical natural areas for scientific research, (3) long—term ecological monitoring, (4) providing conservation training for professionals, (5) initiating environmental education programs (which may include limited tourism), and (6) providing expertise in the environmental impact of regional development projects. For the first time in history, Russian legislation specifically described the rights and responsibilities of zapovednik employees. The legislation consolidated and legitimized a long history of protection and research on zapovedniki located across Russia’s landscape (Federal Law 1995). The majority of zapovedniki are concentrating on the first three goals that date to 1908, and more slowly incorporating the last three goals (Sobolev and others 1995). future transition to active management much easier; (3) the Russian government has repeatedly stated its intention to have 5 percent of Russia protected by 2005—again a relatively cheap method for realizing this goal; and, (4) preserves are political recognition for scientists and the environmental community, which may demonstrate that the Russian government is still concerned about the environment. In a process similar to the Soviet era, the 22 new preserves have been established through the combined efforts of scientists, local conservationists, and Russian conservation organizations. A post-Soviet addition is that international conservation organizations have donated time, money, and staff to support initiatives to establish new zapovedniki (Sobolev and others 1995). Central Administration International Conservation Organizations In July 1995, after lobbying by zapovednik directors and organizations such as the BCC, the Ministry of Environmental Protection established the Department of Nature Reserve (Zapovednik) Management. Vsevolod Stepanitski was appointed to head the new department. Historically, zapovedniki were spread out through various administrative authorities such as local and provincial authorities, the Ministry of Hunting and Game Preserves, the Ministry of Forestry, or the Russian Academy of Science. Although associated with each other in many respects, the preserves lacked a single, unified agency to lobby for their needs and interests (Pryde 1991). Establishment of a centralized department in Moscow provided essential support for the survival of zapovedniki in Russia. The initial focus for the new department was protecting the borders and enforcing laws that prohibited trespass or utilization of resources from the zapovedniki (Williams 1995). Prior to 1995, employees lacked the authority to make an arrest or file suit against offenders. If an employee needed to arrest a poacher, they enlisted the support from the local militia or police—an awkward, time-consuming process. Although each zapovednik is still struggling to pay salaries and maintain a staff, the support from a central administration combined with the 1995 Federal Law for Specially Protected Natural Areas gives the zapovedniki a sense of direction and legal strength. Another positive result from the fall of the Soviet Union is the increased contact with international conservation organizations. In April 1997, the British Environmental Know How Fund supported the development of management plans for two zapovedniki and one national park (Grigoryan 1997). Organizations such as Pacific Environment and Resources Center (PERC) and the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) have been donating time, staff, and funding for several educational initiatives, computer support, training sessions, and conferences. In December 1997, PERC and the Chazy Ecofund in Abakan organized a conference for southern Siberian protected areas. The conference concluded with a master plan for the region to initiate a comprehensive program of biodiversity conservation. Further evidence of international assistance is that the World Conservation Union (IUCN) has representatives in Russia; the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization’s (UNESCO) Man and the Biosphere program has disseminated computer software and training to standardize information from the 17 zapovedniki that are biosphere reserves; and cooperative projects and staff exchanges have been organized through the U.S. National Park Service and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In addition, international research universities are working with zapovedniki and have targeted investigations in areas of particular interest such as the Russian Far East (Amur Leopard, Siberian Crane, and Siberian Tiger) and migrating birds nesting in the Arctic Tundra. System-Wide Growth Paradoxically, despite decreasing funding since 1991 there has been a growth in the zapovednik system. In 1991, there were 77 zapovedniki within Russia’s borders. In 1998, there are 99 zapovedniki and 93 are active—a 30 percent increase since the fall of the Soviet Union. Six preserves are so new they are considered “paper preserves” (Stepanitsky 1998) The paper preserves have no staff or a small volunteer staff, no mechanism for conducting research, and no government inspectors to protect their borders. Although some directors and activists object to paper preserves, the benefits seem to outweigh the drawbacks. Several benefits include: (1) property ownership has not been determined in many areas of Russia, and therefore property is relatively cheap—essentially free—for the government; (2) endangered species need habitat protection, and setting aside land now will make any USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 Environmental Education A recent addition to management strategies for zapovedniki is environmental education. The theory is to increase political support by educating young people about the purpose and role of zapovedniki in Russian society. The long-term expectation is that as adults the students will be less likely to violate the zapovednik regime and more likely to support helpful legislation. The scientific staff on Katun Zapovednik indicated early successes in 1995 after they initiated an outreach program to the schools (Ostergren 1995). In 1996, with support from the World Wide Fund for Nature and the Swiss government, a Zapovedniks’ Environmental Education Center opened in Moscow. The goals are to develop funds and contacts for education, create and adapt educational 211 methodologies, create vivid public education programs, and support local initiatives in environmental education (Menner 1996). Because using the zapovedniki for educational purposes may open them up to the general public, some experts caution against too much access. The primary function of the preserves is protection and monitoring relatively pristine ecosystems. On the other hand, education is viewed as a service to society and necessary to generate and maintain political support. The Education Center believes the zapovedniki are still evolving and defining their role in st society as we enter the 21 century. Careful consideration should be given to the advantages and disadvantages of environmental education for zapovedniki (Danilina 1997). New Challenges For Zapovedniki ____________________ Despite the many positive steps for zapovedniki since 1991, most of the news is bad. The single largest problem for zapovedniki is a lack of funds. From 1991 to 1995, the federal budget shrunk by 60 to 80 percent for all zapovedniki. The result was a cut in salaries for inspectors, scientists, and staff, a shortage of equipment, a drop or elimination of access to helicopters, a reduction in border patrols, a reduction in the number of research projects, and a reduction in the number of cooperative research projects with Russian universities. As directors reacted to the problem, they spent more and more time raising funds from a variety of sources including regional ecological funds, and international research and grantmaking institutions. Innovative solutions included the Altai Zapovednik trading apples for gasoline, inspectors in remote Arctic stations trading salted fish for helicopter support, and the Putoranski Zapovednik helping collect museum specimens on wildlands outside of the zapovednik (Ostergren 1997). In 1995, the Department of Zapovedniki in Moscow began to keep records of violations on the regime of the protected areas. In the 1997 reports of zapovedniki protection services there were 3,503 formal charges (compared to 2,596 in 1996). Violators received penalties in 1997 from administrative fines of 246,745,000 rubles (U.S. $40,225—6.134 rubles/ dollar in May 1998) and 326,481,000 rubles (U.S. $53,225) from suits in compensation for damages inflicted on the nature complex (Stepanitski 1998). The 1995 Federal Law on Specially Protected Areas has proved very useful by authorizing zapovednik inspectors to make arrests and file law suits. Table 1 provides a summary of violations for 1996 and 1997 (Stepanitski 1998). These reports are from 93 active zapovedniki. Several reasons have been postulated for the increase in violations. One is that government inspectors are becoming more efficient at detecting and apprehending violators. In addition, because inspectors are aware that the Department of Zapovedniki in Moscow is interested in these statistics, an increase may be due to increased reporting. However, the largest proportion of increases is due to the social and economic climate of Russia. Fewer restrictions on movement across Russia’s borders mean that poachers have a greater access to international animal parts markets and thus have a greater incentive to violate the regime. The Altai Zapovednik reported an increase in Musk deer poaching in 1993 and 1994 as the price for musk increased. As the price declined in 1995, so did the poaching. Poachers have become more bold as evidenced by an armed raid to steal horses at a government inspector’s station on the Altai Zapovednik, and on Lazovski Zapovednik two inspector stations were burned down. A significant motivation for poaching and trespass is survival. As unemployment rises and food becomes scarce, locals neighboring the zapovedniki turn to hunting and gathering as a source of sustenance. At nearby settlements and summer homes, people gather firewood, berries, mushrooms, and medicinal plants on a regular basis, although they rarely venture far into the preserve. On the Stolby Zapovednik, evidence of poaching elk and deer is increasing on the periphery of the preserve. Despite increased poaching, Director Knorre believes that the interior of the preserve is largely untouched by poaching and trespassing. The greatest strength for zapovedniki in times of economic stress is their sheer size or remote location. The Collapsing Budget In 1998, the proposed budget for all 99 zapovedniki was 43 million rubles (U.S. $7 million). According to Vsevolod Stepanitski in a recent press release, the Department of Zapovedniki was informed that their budget has been reduced to 12 million rubles (U.S. $2 million in a constant exchange rate). This was before the devaluation of the ruble in September 1998. The only item that is supported by the federal budget is the salary line item. No money has been Table 1—A summary of violations on 93 zapovedniki in 1996 and 1997. Violation Wood gathering and cutting Haymaking and pasturing livestock Hunting Fishing Collecting wild vegetation Taking land and building Travel by foot or automobile through the area or parking in the protected area Pollution Irresponsible fire and burning of forest on adjacent lands Poaching ungulates Poaching large predators 212 1996 171 80 439 712 219 38 710 58 41 94 1997 214 46 434 1,007 461 9 1,007 45 63 123 4 (including one polar bear and one Himalayan bear) USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 allocated for maintenance, research, or education. Stepanitski suggests that even with some outside funding the system is in deep trouble. A long-range, multi-pronged approach is necessary to protect Russia’s environment. Federal funding ought to be sufficient to keep the reserves functioning at least on a maintenance basis. Now the directors are faced with the choice of cutting meager salaries or letting some staff go. As of September 1998, several zapovedniki have reported the worst conditions since the fall of the Soviet Union. According to the director at the Kandalaksha State Nature Reserve, they have only 20 percent of the budget of 1992. The staff describes it as a catastrophic situation for the preserve. The overall budget in 1998 consisted of 90 percent from federal government, 0 percent from international NGOs, and 10 percent from local governments. There is a 70 percent reduction in the number of inspector stations on the borders, and the number of government inspectors is down 50 percent. The staff at Kronotskiy Zapovednik report that the 1998 budget is 10 percent of 1992—a drastic reduction. They had 27 inspectors in 1992 and now only 15. The budget for Lazovski Zapovednik in 1998 is much worse than the budget in 1992. Again the federal budget only provides funds for salaries, and since June 1998, salaries have been reduced yet again by 50 percent. Several government inspectors left their jobs stating that the salary is just too low. Conclusions ____________________ Since 1991, zapovedniki have maintained and promoted their role in Russian society by: • Contacting international NGOs. • Using legislation to increase their legal status and ability to enforce the law. • Expanding their environmental education program. • Diversifying their funding strategies. Despite their efforts, the massive reduction in federal support overrides most efforts to fulfill their mandate of biodiversity conservation, ecological monitoring, and environmental education. Director Stepanitski has appealed to the Duma for support, but the legislative body seems unlikely to change this year’s budget. In light of current conditions for zapovedniki the following questions remain. What will zapovedniki do in the next 2 to 5 years to survive? How can the international community support this unique system of wilderness preserves? In the short term, the authors recommend that the international community support the zapovednik system by: • Recognizing its contribution to global biodiversity and wilderness preservation. • Encouraging international NGOs to support both small and large zapovedniki. • Promoting cooperative research projects on zapovedniki. • Supporting ecotourism and scientific tourism that injects income or supports research on a wide range of zapovedniki. Zapovednik directors, administrators, scientists and nongovernment organizations concur that long-term solutions USDA Forest Service Proceedings RMRS-P-14. 2000 will come from within Russia. However, the international community can support zapovedniki through a variety of methods and send a message to the Russian government that this unique system of protected areas is a national and global treasure that deserves federal support and long-term investment. References _____________________ Boreiko, V. E. 1993. Razgrom zapovednikov: kak eto bilo (1951-?), [Destruction of the zapovedniki: how it happened.] Energia. 2: 14-17. Boreiko, V. E. 1994. 1961: Vtoroi pazgrom zapovednikov, [Second destruction of the zapovedniks.] Energia. 1: 35-38. Danilina, N. 1997. Environmental education for the 21st century: shaping the concept. Russian Conservation News. 13: 15-17. Federal Law on Specially Protected Natural Areas. 1995. (Federalnie zakon ob osobo okhranyaemikh prirodnikh territoriyakh). Ekos Inform. 6: 3-56. Grigoryan, A. 1997. Opposing sides in Altai establish a dialogue. Russian Conservation News. 13: 6-8. Kozhevnikov, G. A. 1908. On the necessity of establishing reserve plots in order to conserve the natural resources of Russia. Reprinted in Bulletin No. 4: 73-78. Conservation of Natural Resources and the Establishment of Reserves in the USSR. Translated and published in 1962 by the Israel Program for Scientific Translation, Jerusalem. Menner, A. 1996. First environmental education center for zapovedniki opens in Moscow. Russian Conservation News. 7: 21. Ostergren, D. 1995. Two approaches to the same mission. Russian Conservation News. 6: 5-6. Ostergren, D. M. 1997. Post-Soviet transitions in policy and management of zapovedniki and lespromkhozi in Central Siberia. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University. 213 p. Dissertation. Ostergren, D.; Shvarts, E. 1998. Protected areas in Russia: management goals, current status, and future prospects of Russian zapovedniki. In: Watson, Alan E.; Aplet, Greg H.; Hendee, John C., comps. 1998. Personal, societal, and ecological values of wilderness: Sixth World Wilderness Congress proceedings on research, management, and allocation, Vol. 1; 1998 October 24-29; Bangalore, India. Proc. RMRS-P-4. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station: 11-16. Ostergren, D. M. 1998. System in peril: a case study of five Central Siberian zapovedniki. The International Journal of Wilderness. 4(3): 12-17. Pryde, P. R. 1972. Conservation in the Soviet Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. 301 p. Pryde, P. R. 1991. Environmental Management in the Soviet Union. New York: Cambridge University Press. 314 p. Shtil’mark, F. 1995. Pervimi zapovednikami v Rossii [First zapovedniks in Russia]. Zapovestnik. 7-8(10-11): 6. Shtil’mark, F. R. 1996. Istoriografiya Rossiskikh Zapovednikov (1895-1995). [The Historiography of the Russian Nature Preserves]. Moscow: TOO, Logata. ISBN 5-900858-03-0. Sobolev, N. A.; Shvarts, E. A.; Kreindlin, M. L.; Mokievskiy, V. O.; Zubakin, V. A. 1995. Russia’s protected areas: base survey and identification of development problems. Biodiversity and Conservation. 4(9): 964-983. Stepanitski, V. 1997. Financing Russian Zapovedniki in 1996. Russian Conservation News. 12: 30-31. Stepanitski, V. B. 1998. Several results of work by the protection service for Russian zapovedniki in 1997. [Nekotorii itogi raboti cluzhb okhrani Rossiskikh zapovednikov v 1997 godu.] Zapovedniki and National Parks Information Bulletin. May 29, no. 24-25. Weiner, D. R., 1988. Models of nature: ecology, conservation, and cultural revolution in Soviet Russia. Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. 312 p. Williams, M. 1995. A new department of nature reserve management for Russia. Russian Conservation News. 5: 3. 213