Land Use in the Majjia Valley, ...

advertisement

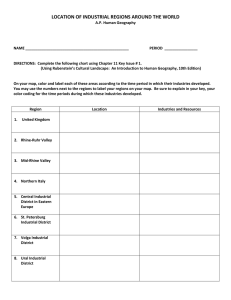

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Land Use in the Majjia Valley, Niger, West Africa 1 Peter F. Ffolliott and Roy L. Jemison 2 Abstract.--A reforestation project in the Majjia Valley, Niger, was undertaken to improve the microclimate, to reduce water and wind erosion, and to produce fuelwood. Windbreaks were planted, woodlots were established, and trees were distributed to the inhabitants. The windbreaks were effective in reducing wind velocities and, at times, retained soil moisture. Water consumption by vegetation in the windbreaks did not affect soil moisture in the agricultural crop rooting zone. Although fuelwood has not been harvested, agricultural crop yields in the windbreaks were higher than those in a control. INTRODUCTION THE MAJJIA VALLEY The Republic of Niger is a country in which two-thirds of the area lies in the Sahara Desert, and the remaining one-third is a semi-arid strip of land known as the Sahel. It is in the Sahel that the majority of people live as sedentary farmers. The plight of these farmers, along with the many nomads in the region, was brought to the attention of the world in 1970-74, when the Sahel was struck by drought. A lack of water and fodder, attributed to the drought, resulted in a loss of approximately 50 percent of the livestock, and forced many people to migrate in search of relief. The Majjia Valley is situated in the arrondissements (counties) of Bouza and Birni'n Konni, Department of Tahoua, in southwestern Niger. The Majjia Valley extends, more-or-less northeast to southwest, covering approximately 25,000 hectares of predominantly agricultural land. The general altitude of the valley is between 300 and 600 meters. Physiography The Majjia Valley consists of a plateau, deeply intersected by wide valleys, which are often temporarily inundated. The edges of the plateau form escarpments, on which boulder pavements are found. Extensive slopes and gentle outwash slopes connect the escarpments with the valley floor. The Majjia Valley is one of the more important river basins in the Sahelian region of Niger. However, it is also considered highly populated for a rural area in West Africa, with nearly 50 people per square kilometer. Intense land use pressures, the most noted being farming, livestock grazing, and wood gathering, have resulted in severe degradation by water and wind erosion and a decrease in available soil moisture and fertility. In 1974, CARE, in collaboration with the Government of Niger, initiated a reforestation project, including the planting of windbreaks. The success of the 3,000 hectares in windbreaks to date is, perhaps, one of the best examples of good riparian zone management in West Africa. Due to a diversity of geologic materials and soil-forming factors, a variety of soils have developed in the Majjia (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). Many of these soils are characterized by relatively high fertility, a situation that is exceptional to this region of Africa. Soils derived from schist or limestone materials are particularly fertile. Alluvial deposits, with very sandy soils in the river beds, occur in the valley itself. Vegetation According to the Yangambi classification, the Majjia Valley lies in the tree savanna zone of West Africa (FAO 1975, as cited by Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). Among the more important woody species in the tree savanna of the Majjia are Combretum spp., Guiera senegalensis, Acacia spp., Bauhinia reticulata, Anogeissus leio~, Ziziphus_ mauri~ Poupartia birrea, and Ficus gnaphalocarpa. However, due to the population pressures and subsequent 1 Paper presented at the North American Riparian Conference on Riparian Ecosystems and Their Management: Reconciling Conflicting Uses. [Tucs~on, Arizona, April 16-18, 1985]. Peter F. Ffolliott is Professor of Watershed Management and Roy L. Jemison is Research Assistant, School of Renewable Natural Resources, College of Agriculture, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 85721. 470 demands for fuelwood, agricultural land, and grazing land, very little of the natural vegetation remains. intercropped with millet (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). Cotton and some peanuts are grown as cash crops during the rainy season. The need for productive agricultural land is so great that almost no fallow land is found. Although the soils are relatively fertile to start with, ~he continued use of traditional farming methods (involving the application of no artificial fertilizer and only a limited amount of manure from the grazing animals) is resulting in decreased productivity. Today, only a few scattered trees protect the landscape from severe water and wiud erosion. As a result, agricultural crop and livestock forage productivity has greatly declined, due in large part to decreased soil fertility and reduced suil moisture retention capacity. In the dry season, village gardening is undertaken on areas where groundwater is avaiJ abJ.e. Tomatoes, lettuce, and tobacco are grown !or local consumption; onions are produced, mostly as a cash crop. Climate Located in the Southern Sahel Zone of Niger, but in the central part of the "true Sahel," the climate of the Majjia Valley is characterized by two clearly distinguishable seasons: a rainy season of 4 months (June through September), and a dry season of 8 months (October through May). Most of the rain, which averages less than 500 millimeters a year, falls during intense thunderstorms, causing severe water erosion. Rainfall maximums occur in August. Many of the lands in the Majjia are used for extensive grazing of cattle, sheep, and goats, as well as donkeys, camels, and horses. Grazing of domestic livestock is also allowed on agricultural lands during the dry season (Bogne~teau-Verlinden 1980). In general, the level of grazing in the Majjia Valley is too intensive for the carrying capacity of the land. The mean annual temperature is approximately 28°C, with a minimum mean monthly temperature of 25°C in January and a maximum mean monthly temperature of nearly 35°C in May. Relative humidities are low, particularly in the dry season when values are less than 20 percent. It has been estimated that potential evaporation exceeds 3 meters a year (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). Niger is located in that part of West Africa affected by the northeastern trade winds and the southwestern monsoon, the latter being a carrier of rain. Hot, dry winds of relatively high velocities often carry large amounts of dust, especially during the dry winter months (November through April). With little vegetative cover, the erosive power of these winds is significant. People The population of the Majjia consists, for the most part, of Haussa farmers, who live in villages along the valley floor. On the lower slopes, villages of the Bouzou people, sedentary cattle-breeders, are found. Also, some Fulani, who are essentially semi-sedentary nomads, live in the area. As mentioned above, the population density in the Majjia Valley, including the lower slopes, is over 50 inhabitants per square kilometer and is increasing. During the dry season, a large portion of the younger male Haussa population leaves the Majjia for seasonal work. However, a large portion of the population remains on-site throughout the year, surviving as best they can until the rains arrive. All of the land belongs to the central government, but traditionally, the inhabitants are responsible for the free distribution of agricultural land among the villagers. Once obtained, the rights to work the land are heritable, although the land can be leased or sold with the village chief as a witness. Through a reforestation project, the forestry service in Niger is attempting to reclaim as much land as possible to improve the microclimate of the area, to protect the area against water and wind erosion, and to produce needed fuelwood supplies. The reclamation activities include planting of windbreaks, establishing village woodlots, distributing trees (free of charge) for live fencing, and creating small private woodlots and planting shade trees. Concurrently, the forestry service is attempting to protect the remaining natural vegetation through educational work and protective activities. Hore details of the "Majjia Valley Reforestration Project" are presented below. Erosion Water and wind erosion in the Majjia Valley is severe. In fact, this area is one of the most threatened in West Africa, with an estimated soil loss of over 2,000 tons per square kilometer a year (Delwaulle 1973, as cited by Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). This high erosion rate is easily understood through a review of prevailing climatic patterns and land use practices in the area. As mentioned above, the Majjia is characterized by a rainy season with intense storms, a prolonged dry season with continuous winds in a direction parallel to the valley, and physiographic features that cause low permeability and high runoff. At the same time, a high population is exerting pressures on the land, causing a general deterioration of the vegetative cover and, therefore, a high susceptibility to water and wind erosion. Land Use The Majjia Valley, including the temporarily inundated area, is an important agricultural area. Important crops are millet, sorghum, and niebe, the latter being a protein-rich bean that is 471 In large part, it was because of the severe water and wind erosion problems, along with an attempt to stabilize the livelihood of the rural families, that the "Majjia Valley Reforestation Project" was initiated. plants a year, although it will expand in the future. Seeds are collected from locally grown trees, planted in polythene bags, and grown in the nurseries for a period of 4 to 7 months. In addition to neem, limited numbers of Acacia seyal, Acacia scorpioides, and Prosopis juliflora seedlings are produced. MAJJIA VALLEY REFORESTATION PROJECT In 1974, the forestry service in Niger and CARE entered into an agreement to undertake a forestry project to counter the severe effects of water and wind erosion and declining agricultural productivity. Originally funded by CARE, the project has also received support from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), through a matching grant (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). The project area encompasses about 6,000 hectares of the Majjia Valley, approximately onehalf of which is currently protected by windbreaks. Planting Methods For the windbreaks, the lines of trees were planted in holes (40 x 40 centimeters wide, 60 centimeters deep) dug by the v~llagers. In the initial years of the project, the trees were planted in a 4 x 4 meter rectangular spacing pattern. Subsequently, a 4 x 4 meter triangular spacing was adopted (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). The trees were planted by the nursery workers, again with the assistance of the villagers, after the first or second heavy rain of the season, usually in July. Following planting, no additional watering of the trees was done. The "Majjia Valley Reforestation Project" actually began in 1975, with the planting of 13 kilometers of windbreaks in double rows of neem (Azadirachta indica) trees, planted 4 meters apart. Today~years later, the main activity of the project remains the planting of windbreaks; over 400 kilometers, along parallel corridors, have been planted. Other components of the project include free distribution of tree seedlings, riverbank protection, and the establishment of village and private woodlots. Planting of the village woodlots was done by the forestry service, in a 3 x 3 meter spacing. Land required for these plantations was selected by the forestry service, in consultation with the inhabitants. For the other components of the reforestation project, trees were freely distributed to or collected by the villagers, during the rainy season. In general, the villagers cared for the tree plantings themselves, withadvice from the forestry service. Goals of the Project In essence, the two major goals of the "Majjia Valley Reforestation Project" are to: 1. 2. stabilize, and if possible, increase the agricultural income of rural families in the Majjia through tree planting activities, and protect agricultural lands from erosion and crops from the detrimental influences of desiccating winds; and Protection and Maintenance During the initial two or three years after planting, the trees were protected against grazing by domestic livestock and bush fires. For the windbreaks, this protection was achieved by guardians, who removed the grazing animals (BognetteauVerlinden 1980). The guardians were frequently assisted by the farmers in the wet season. This system worked fairly well, and enclosure of the windbreaks was not needed. After three years, the trees were large enough to resist the browsing of livestock. improve the ecological balance of the area, stimulate conservation efforts, and improve the environmental situation through protection of endangered natural resources by providing tree seedlings for planting on agricultural lands, in village and private woodlots, and in private compounds. Farmers, who previously did not need to clean their fields because the weeds and crop residues were eaten by the livestock, found it necessary to clean their fields by prescribed burning. However, close control of the fires was requisite to avoid damaging the young trees. Tree Nurseries A key to the success of the "Majjia Valley Reforestation Project" is the operation of nurseries which, upon request, supply the necessary planting stock for the project activities. Until 1983, two nurseries produced 30,000 tree seedlings a year. Recently, a third nursery was opened, located about midway between the original nurseries (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). The current production level of this third nursery is 15,000 The village woodlots were fenced with chicken wire for the initial few years of establishment. After this, the commonly planted Prosopis juliflora formed live fencing, which provided sufficient protection for the growing trees. The distributed trees were protected against grazing by livestock with traditional means of 472 individual protection, including thorny branches, millet stalks or grass mats, woven branches, and poles with chicken wire. theoretical height of the millet crop, were reduced to between 40 and 70 percent of the "free" wind velocity. At this height, the maximum reduction in wind velocities was recorded at 1-H to the leeward of the windbreaks. During the initial two years of establishment, the windbreak lines were cleared to avoid competition of weeds. This clearing was carried out by the farmers and guardians during the rainy season; as the agricultural fields extended, in general into the windbreak lines, the farmers simply applied the same weeding techniques here as in their fields (Bognetteau-Verlinden 1980). In general, wind erosion was greatly reduced by the windbreak system, although direct measurement was not made. From on-site observations, it appeared that the overall effectiveness of the windbreak system in reducing wind velocities, and consequently, wind erosion could be improved by creating a higher density of vegetation near the ground in the lines of windbreaks. The village woodlots were maintained by the forestry service and the farmers, primarily through the cutting down of weeds in the initial two years after planting. The freely distributed trees were maintained (weeding and, if necessary, pruning) by the individual villagers. Available soil moisture ~n the windbreak system was greater than that on an adjacent "control" during periods of high water supply. With a low water supply, available soil moisture in the windbreaks was less than that on the "control," although better plant growth was observed in the windbreak system. Water consumption by the vegetation in the windbreaks did not seem to affect the amount of available soil moisture in the most important rooting zone of the millet crop. Harvesting Through 1984, harvesting of wood products has not taken place in the windbreaks or in the other kinds of plantations created by components of the reforestation project. However, based on the results of an intensive evaluation of the "Majjia Valley Reforestation Project," which is currently underway, it is conceivable that limited harvesting may be prescribed in the future. Agricultural crop yields, primarily millet, inside the windbreak system were nearly 130 percent of those on the "control," ranging from 150 percent at a distance of 5-H leeward to the windbreaks at 110 percent at a distance of 16-H. Of course, no millet production was possible underneath the neem trees once the canopy was closed. Nevertheless, correcting for the loss in production underneath the trees, overall production of the millet reached 125 percent of that measured on the "control" site. PRELIMINARY EVALUATION Quite possibly, the most important component of the reforestation project is the system of windbreak plantings. Therefore, a preliminary evaluation of the windbreak system was undertaken in 1979-80 to determine the influence of the windbreaks on: 1. reducing wind velocities; 2. increasing available soil moisture for plant growth; and 3. in~reasing The results of this preliminary evaluation were encouraging. However, it was recommended that, before definitive conclusions on the impacts of windbreaks are drawn, and before widespread replications of the "Majjia Valley Reforestation Program" can be promoted, more detailed research and subsequent evaluation are required. Therefore, an intensive evaluation study, jointly undertaken by CARE and USAID, was formulated in 1984 (CARE 1984). agricultural crop yields. Details of the measurement techniques employed in the preliminary evaluation have been outlined in the evaluation report and, therefore, will not be described in this paper (BognetteauVerlinden 1980). Instead, a brief summary of the major conclusions is presented in the following paragraphs. A principle "benefit" of this detailed evaluation study will be a better understanding of the interactions among people, trees, and agricultural crop production under a windbreak system, an important agroforestry system. Additionally, it will serve to assist the Government of Niger in more effectively utilizing those resources that are designed for reforestation interventions. It should also help to broaden the base of reliable information needed by developmental planners in the West African Sahel. Wind velocities inside the windbreak system, measured at 1 meter above the ground, were decreased to approximately 45 to 80 percent of the "free" wind velocity. This height was considered high enough to disregard the surface roughness factors, but low enough to indicate the erosive force of the winds. The maximum reduction in the wind velocities occurred at 5-H to the leeward of the windbreaks, a distance of 5 times the average height of the trees in the windbreaks. SUMMARY When a drought in 1970-74 caused a 50 percent loss of the livestock and forced migration of the sedentary farmers in the Hajj ia Valley, a reforestation project was undertaken by the forestry service in Niger, in conjunction with CARE and USAID. The objectives were to improve the microclimate of Wind velocities at 2.5 meters above the ground, a height selected to represent the 473 of the millet. Additionally, agricultural crop yields were 125 percent of those in the control. the area, to protect against water and wind erosion, and to produce fuelwood. To accomplish these, windbreaks were planted, village and private woodlots were established, and trees were distributed (at no charge) to the inhabitants to plant for live fencing and to provide shade. Newly established nurseries grew seedlings (from locally collected seeds) for the plantings. Before this reforestation project can be replicated in other riparian zones in the Sahelian region, more research and evaluation are necessary to better understand the interactions among people, trees, and agricultural crops in windbreak systems. Although no harvesting of fuelwood has taken place, the windbreaks proved to be effective. Wind velocities were reduced significantly at both 1 meter and 2.5 meters (the theoretical height of millet) above the ground, with maximum wind reduction 5-H and 1-H, respectively, to the leeward sides of the windbreaks. It was speculated that higher density vegetation near the ground would be more effective in reducing wind erosion. LITERATURE CITED Bognetteau-Verlinden, Els. 1980. Study on impact of windbreaks in Majjia Valley, Niger. CARE, 81 p., Niamey, Niger. CARE. 1984. Proposal for an evaluation study of CARE's Majjia Valley Windbreak Project. CARE, 55 p., New York, New York. Delwaulle, J. C. 1973. Resultats de six ans d'observations sur l'erosion au Niger. Bois et Forets des Tropiques, No. 150, 132 p. FAO. 1975. Methods de plantation forestiere dans les savanes Africaines. FAO Collection: Mise en Valeaur des Forets, 113 p., Rome, Italy. Available soil moisture was greater in the windbreak than on the control when water supplies were high, however, the opposite was found when water supplies were low. Water consumption by vegetation in the windbreaks did not affect available soil moisture in the important rooting zone 474