Nest Boxes as a Coppery-Tailed Trogon M•nagtment Tool

advertisement

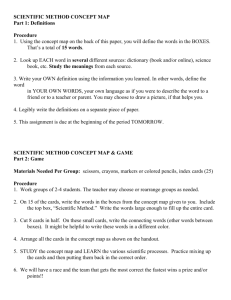

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Nest Boxes as a Coppery-Tailed Trogon M•nagtment Tool 1 Wendy A. Hakes 2 Abstract.--Thirty nest boxes designed for Copperytailed Trogons (Trogon elegans) were observed in the Huachuca Mountains of southeastern Arizona from 1979-82. No trogons used them, but 7 vertebrates did. This study indicates nest boxes may not be an important management tool for trogons, but may be useful for other North American holenesters. INTRODUCTION used as a management tool to increase the population of Coppery-tailed Trogons in Ramsey and Sunnyside Canyons in the Huachuca Mountains. A secondary objective was to gain additional information about the effects of competition, predation, and human disturbance on trogon nesting success. The Coppery-tailed Trogon, a cavity-nesting bird, breeds in southeastern Arizona and Mexico. Approximately 100 trogons arrive in Arizona each April to occupy the pine-oak woodlands adjacent to the riparian habitats of the Chiricahua, Huachuca, Santa Rita, and Atascosa Mountains (Taylor 1980). I gratefully acknowledge the help given by the following people: J. Anderson for initiating this study; S. Crabtree, S. Peckham, and Boy Scout Troop 700 for building boxes; R. Taylor for his suggestions; the staff of the Ramsey Canyon Preserve, the Arizona Nature Conservancy, and United States Forest Service for their cooperation and assistance; bird-watChers and students for their field observations; J. Anderson, J. Dunning, J. Hardison, P. Krausman, S. Mills, and R. Taylor for identifying box contents; and D. Fuller, T. Huels, W. Mannan, and W. Shaw for editing suggestions. The human interest in Coppery-tailed Trogons is great--approximately 25,000 bird-watchers visit Arizona each year to see trogons and other birds unique to southeastern Arizona (Taylor 1980). The trogon population in Cave Creek Canyon of the Chiricahua Mountains is the most accessible and the most frequently visited by birders. Trogons, apparently, will not re-nest during a season if their eggs are destroyed.3 Concern about harrassment of the birds and resulting nest failures prompted the U.S. Forest Service to prohibit the use of tape recorders to attract wildlife in Cave Creek Canyon since this disturbs breeding trogons. METHODS Nest boxes have been used as a management tool for many North American vertebrates where there is believed to be a deficiency of natural cavities (Schemnitz 1980). Providing artificial nest structures resulted in an increase in breeding density of several species (Strange, et al. 1971; Hamerstrom, et al. 1973). This study was undertaken to determine if nest boxes could be Thirty nest boxes were built to conform to the average dimensions of known trogon nests (table 1, fig. 1).3 Three-quarter inch pine and fir were used to provide adequate insulation (Kibler 1969). A traditional square and an octagonal design were used. The 8-sided shape made the boxes more tree-like in appearance. The outside surfaces were painted with a brown nontoxic paint to decrease the conspicuousness of the nest boxes. They were lined with an inch of dry grass and leaves and this lining was changed each season. 1Paper presented at the snag habitat management symposium. [Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, June 7-9, 1983]. Twelve boxes were erected in Ramsey Canyon fn 1979 at junctions of the main canyon with side canyons. Previous studies indicated that these locations are attractive nest sites for trogons.3 The remaining 18 boxes were erected in 1980 and had smaller entrance holes to limit access to predators (table 1). The 30 boxes were placed at heights ranging from 14-26 feet. Predator deterrents were put on 4 boxes after evidence of use lwendy A. Hakes is a senior in Wildlife Ecology, University of Arizona, Tucson, Ariz. 3Taylor, R. C. 1978. Preliminary report: the distribution, population and breeding biology of the coppery-tailed trogon in Arizona. Unpublished report. 147 Table 1.--Dimensions of Coppery-tailed Trogon nest boxes. Box Dimension Measurement -(inches)-- 1-30 1-30 1-30 1-12 13-22 23-30 depth interior exterior entrance hole entrance hole entrance hole 16.0 5.5-6.0 6.3-6.8 3.5 2.5 2.4 by Ringtails (Bassariscus astutus) increase,l (fig. 2). The boxes were checked every 2-3 weeks from early April to mid-August and the contents were examined after the young trogons in natural cavities had fledged. In 1982, questionnaires were given to bird-watchers at the Ramsey Canyon Preserve to supplement these observations. Birders were asked to provide information such as the activity, location, sex, and age of trogons in Ramsey and Sunnyside Canyons. Figure 2.--Predator deterrent. Use of Boxes by Other Animals Although apparently not attractive to trogons, the boxes were used by several other birds: Flammulated Owls (Otus flammeolus), Whiskered Screech-Owls (Q. triChopsis), Ash-throated Flycatchers (Myiarchus cinerascens), and Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis) nested in the boxes (table 2). In 1982, Northern Flickers (Colaptes auratus) used 2 boxes as dump sites to lay extra eggs in. No Coppery-tailed Trogons nested in the boxes during the 4-year study, although 1 male did investigate a box in Ramsey Canyon.4 The populations in both canyons fluctuat~d slightly between years but did not increase. Ramsey Canyon had an average of 2 males and 1 female, and Sunnyside Canyon's population averaged 5 males and 3 females.5 The most frequent mammalian use of the nest boxes was roosting by Ringtails. Arizona Gray Squirrels (Sciurus arizonensis) also nested in at least 1 box. DISCUSSION -- removable lid Numerous variables co~ld explain why Copperytailed Trogons did not use the nest boxes. These factors include statistical chance, population dynamics, entrance hole size, location within territories, competition, predation, human disturbance, nest tree status, physical attributes of location, height, and an abundance of natural nest sites. --+-- ~ inch hardware cloth The lack of use by trogons possibly is due to statistical chance. Compared with the number of natural nest cavities, the number of nest boxes. is very small and the lack of use by the few nesting trogons simply may be due to chance. The population dynamics of Coppery-tailed Trogons in the United States may also be a contributing factor to the lack of use of the boxes. The Arizona population of trogons is small and is at the edge of its range. As such, this population may already be reproducing at its maximum potential. This idea appears to be supported by the presence of unmated males every year in all 4 mountain ranges. identification number Figure 1.--Coppery-tailed trogon nest box. The small entrance holes (2.4 and 2.5 inches) of 18 of the boxes may have discouraged use by trogons. These holes were at the low end of the range of hole sizes Taylor recorded for 38 natural nests. Only 2 nests have been recorded in the United States with holes under 3 inches in diameter.5 4 Rule, Virgil. 1982. Personal conversation. The Arizona Nature Conservancy, Tucson, Ariz. 5 Taylor, R. C. 1982. The coppery-tailed trogon in Arizona, 1962. Unpublished report. 148 Table 2.--Use of Coppery-tailed Trogon nest boxes in Ramsey and Sunnyside Canyons, 1979-82. Species 1979 1980 1981 1982 Total 1 Coppery-tailed Trogon Flammulated Owl2 Whiskered Screech Owl2 Northern Flicker Ash-throated Flycatcher2 Eastern Bluebird2 Ringtai13 Arizona Gray Squirrel2 Invertebrates Investigated/roosted Total 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 3 0 10 16 24 0 0 0 0 1 1 5 2 14 8 23 0 0 0 2 1 0 4 1 13 9 25 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 6 1 8 1 2 1 1 8 2 23 20 28 1Number of boxes used in 4 years. 2Boxes used for nesting. 3Boxes used for roosting. In Sunnyside Canyon, most of the boxes were placed in areas occupied by trogons. Successfully breeding trogons keep other trogons out of their territories and often re-use previously used nest cavities. Consequently, other trogons may not have had a chance to investigate the nest boxes and the territorial pair continued using an old site. The logical solution would be place the boxes outside of trogon territories, but in Sunnyside Canyon, all suitable habitat appears to be occupied. cavities and, consequently, there is no reason to assume it affected their potential use of the nest boxes. As secondary cavity-nesters, Coppery-tailed Trogons use existing cavities instead of excavating their own nests. Most natural nests are found in dead and dying trees5, because it is easier for woodpeckers, the original excavators, to drill in the softer wood (Kilham 1971; Conner, et al. 1976) that is a result of aging. I do not believe, however, that the placement of the nest boxes in live trees discouraged trogon use. Competition between Coppery-tailed Trogons and other species for nesting cavities may have contributed to the lack of nest box use by trogons. Steele (1966) recorded a pair of trogons preempting a Northern Flicker pair from a cavity with 2 entrances. In 1982, I watched a male trogon drive a Sulphur-bellied Flycatcher (Myiodynastes luteiventris) from a cavity where the female trogon was incubating. Similar interactions between this cavity-nesting flycatcher and trogons have been observed in southeastern Arizona.3 A Whiskered Screech Owl was found roosting in a cavity previously used as a nest site by trogons and this species also roosted in the nest boxes. The other species that used the boxes also represent potential competitors for nest or roost sites, and, in some instances, the competitor may also be a predator. Heavy use of the nest boxes by Ringtails may present a threat to the trogons. However, I have no first-hand evidence of predation on Coppery-tailed Trogons. The physical attributes of the locations of the boxes does not seem to have been an important factor in the lack of use by trogons. All of the nest boxes were situated in habitat that was similar to that in which trogons nest and therefore presumably were suitable locations. The nest boxes were placed within the know range of heights for natural nests and consequently this should not have discouraged use. A final point that should be stressed is the possibility that the availability of natural cavities is not a limiting factor in Arizona Coppery-tailed Trogon populations. The possibility also exists that the trogons find artificial nest cavities unsuitable for reasons we have not yet identified. CONCLUSIONS Bent (1960), Steele (1966), and Taylor6 recorded nest failures due to human disturbances, such as nest photography, harrassment, and shooting. Both Ramsey and Sunnyside Canyons are heavily used areas for multiple purposes. However, in this study, there was no evidence of human activities influencing trogon use of natural Coppery-tailed Trogons did not use any of 30 available nest boxes in 4 years. However, 5 bird species, 2 mammal species, and numerous invertebrates did use them. Nest boxes do not appear to have much potential as an important management tool for Coppery-tailed Trogons in the United States. Protection of trogon habitat no doubt is the most important management strategy (Pratt 1979). 6Taylor, R. C. 1981. The coppery-tailed trogon in Arizona, 1981. Unpublished report. 149 Kilham, L. 1971. Reproductive behavior of yellowbellied saps uckers. I. Preference for nesting in Fames-infected aspens and nest hole interrelations with flying squirrel s, raccoons, and other animal s . The \Vilson Bulletin 83: 159171. LITERATURE CITED Bent, A. C. 1964. Life historie s of North American cuckoos, goatsuckers, hummingbirds, and their allies. 244 p. Dover Publications, Inc., New York, NY . Pratt, J. 1979. Exploiting the trogon. Wildlife Views 22: 11. Conner, R. N., 0. K. Miller, Jr., and C. S. Adkisson . 1976. Woodpecker dependence on trees infected by fungal heart rot. The Wilson Bulletin 88: 575-581 . Arizona Schemnitz, S.D., ed. 1980. Wildlife management techniques manual. 686 p. The Wildlife Society, Washington, D. C. Hamerstrom, F. 1 F. N. Hamerstrom , and J. Hart. 197 3. Nest boxes: an effective management tool for kestrels . Journal of Wildlife Management 37: 400-403. St eele, E. 1966. Arizona 's mystery bi rd. 68: 167-170. Kibler, L. F. 1969 . The establishment and maintenance of a bluebi rd nest-box project: a review and commentary. Bird-Banding 40: 114-129 . Strange, T. H. , E. R. Cunningham, and .T. W. Goertz . 1971. Use of nest boxes by wood ducks in Mississippi . Journal of Wildlife Management 35: 786-793. Audubon Taylor, C. 1980. The coppery-tail ed trogon: Arizona's "bird of paradise." 48 p. Borderland Productions, Portal, Ariz. 150