Winter Communal Roosting In the Pygmy ...

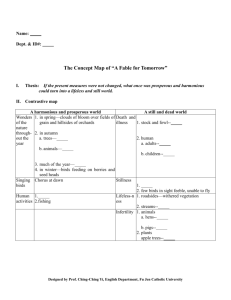

advertisement

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. Winter Communal Roosting In the Pygmy Nuthatch 1 William J. Sydeman and Marcel Gilntert 2 Abstract.--We have studied tbe communal roosting behavior of Pygmy Nuthatches in one extremely important cavity in a snag. Between 27 and 167 birds used the roost during the winter of 1983. Some nuthatches moved almost 2 kilometers nightly to reach this cavity. The number of birds and time of roosting were effected by weather conditions. INTRODUCTION Cavities in snags provide essential habitats for birds during many phases of their life histories. For migratory species, cavities provide the proper thermodynamic and protective environments for rearing young. Resident species may use cavities for predator avoidance and energy requirement during the non-breeding season as well. In particular, the survivorship of many over-wintering species may depend solely on their use of snags. The fmportance of snags may be underestimated with regards to the survivorship of many forest dwelling birds. The Pygmy Nuthatch (Sitta pygmaea) relies on cavities during the winter for survival. Pygmy Nuthatches are one of the smallest (10-11 grams), resident birds of the Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa) forest near Flagstaff, Arizona. They are highly social, and live in groups of 5-20 individuals throughout the non-breeding season. In winter, nuthatches forage in flocks of 4-20 or more that jointly defend a group territory from conspecifics. In the late afternoon, birds gather and travel to a snag within their territory to spend the night. These communal roosts vary in volume and number of birds using them. The snag, where a communal roost is located, is the central focus of wintering birds (Norris, 1958). The largest reported roost of Pygmy Nuthatches is that of Knorr (1957), who estimated 150 birds using a snag in a montane area of Colorado. factors that play a role in promoting large roosting aggregations. Additionally, we will describe the distances traveled by nuthatches to reach this cavity, and the composition of this roosting association in terms of foraging flock membership. METHODS We have been studying Pygmy Nuthatch social organization and breeding biology at Walnut Canyon National Monument and in adjacent Coconino County Forest Service land since October, 1980. The study area is approximately 300 ha., 24.0 km. east of Flagstaff, and is dominated by mature stands of Ponderosa Pine with occasional patches of Pinyon Pine (Pinus edibilus), Juniper (Juniperus spp.) and Gambel's Oak (Quercus gambelii). Many snags are available to the birds in the National Monument, whereas few are present in the Forest Service land due to firewood cutting practices. A large percentage of birds within this area have been color-banded to follow individual life histories. Nuthatches were banded with a unique color-combination. Group foraging territories have been mapped as a result of afternoon observations on the number of birds and identity of individuals in each group. At approximately 1500-1600 hours, observations began at Walnut Canyon 50 (hereafter WCSO), the communal roosting snag used extensively in 1983. The arrival of nuthatches was recorded for as many nights as possible from 14 January to 9 April, ·1983. Generally, two well-trained observers participated in gathering data on the number of birds, and on the identity of individuals. Nuthatches were viewed entering the cavity using either a Bushnell Spacemaster o~ a Bausch and Lomb Explorer spotting scope(s). · Here we report on the communal roosting behavior of a large population of Pygmy Nuthatches in one particularly important snag during the winter of 1983. We will examine the biotic and abiotic 1Paper presented at Snag Habitat Management Symposium. Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, Arizona, June 7-9, 1983. 2william J. Sydeman is a graduate student in the Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ, and Dr. Marcel Guntert was a post-doctorate student at NAU. Presently, Dr. Guntert is Professor of Anatomy, Universitat Irchel, Zurich, Switzerland. We restricted our analyses to evenings when only a full complement of the data were obtained. For example, only those evenings when a full count was made on the number of birds roosting were used for statistical analysis. Similarly, only those nights when we were certain to have arrived before 121 any birds had entered the roost were used in the analysis of time of roosting. numbers. This is insufficient in describing the observed roosting association. Either additional data are.needed on the eff-ect of weather parameters on nuthatch roosting behavior, or biological factors, possibly social constraints, play a role in maintaining large numbers of roosting birds. All regression models ..were developed- usingSPSS forwara or stepwise procedures. RESULTS Table I.--Analysis of Variance Table for the Regression of the No. of Birds Counted Nightly with Weather Conditions (n=33). Number of Birds and Time of Roosting A total of 33 accurate evening counts were made on the number of birds roosting in WC50. The count varied considerably with a high of 167 on 19 February and a low of 27 on 10 March (fig. 1). Source df R2 F Presence of Snow Maximum Daily Temp. BP @ 1700 Day Residual 1 1 1 1 28 .26 .29 .33 .36 10.66 6.05 4.77 3.89 Signif. p p p p <.005 < .01 < .01 <.025 Data presented with the addition of each variable listed • ... 0 Weather conditions notionly affected the number of birds using this snag, t~ey were important determinants of the initiation of roosting. Temperature at 1700 hours and the presence of snow account for 54% of the variation in: roosting times (Table 2).- Temperature is positiv~ly correlated (r = .71, p < .0005) with the time of roosting. On days when the temperature at 1700 hours was higher, the birds roosted later. Snow was negatively correlated (r = -.61, p < .0005). When snow covered the ground, birds roosted at an earlier time. A confounding effect is seen with day in the winter cycle which contributes an additional 16% to the model. As would be expected, daylight hours lengthened following the winter solstice, and the birds entered the roost at later times. The full model in this case predicts accurately when birds go to roost. From these data, it does appear that temperature and snow change Pygmy Nuthatch roosting behavior. 'TI 12 IZI ii 0 "'0 c ...zm () 0 2 MAR FIGURE 1. I 8 MAR liO MAR 9 APRIL NUMBER OF BIRDS AND GROUPS COUNTED NIGHTLY Figure I.--Number of birds (left y-axis) and number of banded group (right y-axis) observed each night coming to WC50. A steady increase in the number of roosting birds and the number of banded groups coming to roost is apparent from the beginning of the study through the first three weeks of February. Subsequently, the number of roosting birds dropped and peaked until the middle of April. These data suggest that roosting is a group phenomenon, and that the decision of where to roost is carried out as a group function, and not by individual birds. In addition, the consistent use throughout early February followed by a sudden decrease in numbers within a matter of days suggests that nuthatches are behaviorally tracking changes in environmental conditions. A threshold temperature or weather condition may trigger use of this snag as a roost. Table 2.--Analysis of Variance Table for the Regression of the Time of Roosting with Weather Conditions (n=33). Multiple regression analysis reveals that weather conditions do indeed affect the number of roosting birds. The presence of snow is the best predictor of cavity use and accounts for 26% of the variability in roosting numbers (Table 1). Temperature, barometric pressure and day in the winter cycle contribute an additional 10% in explaining the number of roosting individuals. Other predictor variables that were entered and found to be insignificant are minimum nighttime temperature, relative humidity, wind speed, cloud cover, and changes in barometric pressure. The full model explains only 36% of the variation in roosting Source df R2 F Signi£. Temp. @ 1700 hrs. Day Presence of Snow Residual 1 1 1 29 .50 .66 • 70 31.319 29.159 22.985 p < .0005 p < .0005 p < .0005 Data presented with the addition of each variable listed. Regression Equation: Y= 1405.43 + 5.35 (Temp. @ 1700) + 1.01 (Day) - 37.28 (SnowP). Roosting Composition The roost contained not only banded, but also many unhanded individuals. The number of banded and unhanded birds in each group, and the distance traveled by each flock to the communal roosting snag are summarized in Table 3. Most of the groups 122 I I contributed more to the roost than others. Generally, these were groups closest to the roosting snag. 1 Light Blue-east and west\and Orange compose the core groups of the WC50 roosting association. White and Red, whose territories are 1.7 and 1.5 km., respectively, from the roost, exhibited similar contributions to the cavity as did these closer groups. The Light Green and Dark Blue groups contribute least, although their presence at the roost is consistent. Yellow-east and west and Mauve contribute significantly to the roost and their distances range from .9 km. to almost 1.5 km. Table 3.--Characteristics of Foraging Flocks of Pygmy Nuthatches. Group No. Banded No. Unhanded 9 5 6 2 2 6 5 6 3 3 9 0 2 2 5 3 2 5 12 3 13 LB-east Or LB-west DB-8 Y-east Y-west LG-west DB-east LG-east Mauve Red White Park-west 11 9 8 9 1 Total No. 12 8 15 2 4 8 10 9 13 14 20 12 14 Distance to WC50(km.) 0.664 o. 715 0.859 0.952 0.974 1.046 1.176 1.248 1.256 1.429 1.509 1.682 0.332 Cavity Characteristics WC50 is located in a dying Ponderosa Pine 78 feet above ground. The cavity has two entrances at equal heights, and located on the underside of broken-off branches where they intersect the trunk. One entrance faces to the northeast, while the other has a southwest exposure. have at least 50% of their birds banded. All banded groups were located east of WC50. The distance traveled to the roost varied from .3 km. to 1.7 km. A total of 141 birds were monitored by taking observations on these banded foraging flocks. At least 79 of these birds were banded and 62 were unhanded. On 19 February, when the highest count of 167 birds was obtained, 96 unhanded birds were observed. Thus, in addition to our banded flocks, other groups of nuthatches from outside the study area were using WC50. The number of these groups is unknown, but the distance traveled to this snag was probably similar to those groups located to the east. All of the banded flocks have been observed roosting at WC50. Banded birds whose complete color-band combination was determined comprised approximately 50% of all banded birds observed. Figure 2 shows the percent contribution of each banded group. It is clear that certain groups .I 0 > < m .o 8 ::u > Ci) m .o 6 0 .o 4 - ....r-- 0 z ..... ~ .o 2c ..... 0z A more realistic assumption may be that the birds are not stacking, but are clinging to the walls of the cavity. An estimate of minimum surface area would then be appropriate in determining cavity size. The area needed to accommodate the ventral 2 surface of a Pygmy Nuthatch is approximately 30 em • Taking our high count of 167 birds~ this means that a minimum surface area of 5,010 em is necessary. A measurement of this magniture is equivalent to a bit more than .5 m2. ,._ r-- r-1-- - DISCUSSION ....- The use of WC50 has increased dramatically this year over previous winters. Traditionally, only Light Blue-east and west, Yellow-east and west and Orange have used WC50 as a winter roost. Why have these additional flocks joined the roosting association at WC50 this year? This is especially puzzling considering that many winter cavities used by these new groups in previous years are still intact. We have already shown how weather ~banges affect the number of roosting birds. -These data, unfortunately, are insufficient in explaining the total variation in roosting numbers. Since these data are preliminary, we cannot explain fully the increased use of this cavity. ....r-- - Be OR 1.8111 DBB Ye YW 0111 DBe LOt .. R Exact cavity characteristics have not been taken owing to the height of the entrances. However, we can estimate the total volume and surface area needed to accommodate the maximum number of birds counted by extrapolating data collected on another previously measured winter roosting cavity. One particular cavity measured 1500 cc. and held, when packed, a maximum of 42 birds (D. Hay, pers. comm.). These nuthatches, in order to fit into this cavity, must have been stacking on top of one another• · Stacking has been observed in aviary birds by groups of 4-12 individuals (D. Hay, pers. comm.). If the birds using WC50 stack, then a minimum of four times 1500 cc. must be available to fit the 167 birds observed roosting on 19 February, 1983. Therefore, the cavity must be at least six liters. w GROUP IDENTITY FIGURE 2.PERCENT CONTRIBUTION OF BANDED GROUPS Figure 2.--Percent contribution of each banded flock to the roosting association. Contribution is computed using only banded birds. Groups are listed in order from the closest to the furthest from the roosting snag. 123 There are, however, a number of theoretical hypotheses in reference to birds roosting in trees or in open areas that may provide some insight into communal roosting by the Pygmy Nuthatch. Lack (1968) proposed that communal roosts function to protect individuals from predators; certain birds roosting in the center of the group may be buffered by peripheral birds when a predator attacks. Ward and Zahavi (1973) have been proponents of the information-center hypothesis which is based on a differential in foraging success between individual birds. Communal roosts then funcfion in the sharing of food localities or foraging techniques between less successful and successful forages. Weatherhead (1983) has synthesized these two hypotheses and suggests that successful foragers are simultaneously dominant individuals in the roostfng aggregation, and as such may secure the most predator proof position within the roost. As of yet, we have not tested any of the above hypotheses. as these requirements change over time and are different for each species. Finally, one might argue that only one cavity is needed to provide a large number of birds with a suitable roost. However, the system we have studied is highly plastic, with fluctuations in cavity usage between years and within seasons. In previous years, other winter roosting cavities were used with equal frequencies of WC50 this year. The availability of numerous snags with cavities having the proper characteristics is critical to nuthatches and other species that rely on snags for over-wintering habitat. Lastly, there are a number of important management implications concerning commooal roosting in the Pygmy Nuthatch. First, if a large communal roost can be identified, the birds using it may be monitored to assess population density. As the birds utilizing WC50 traveled minimum of • 3 km. to almost 2 km. to reach this snag, a large area may be effectively censused with little expenditure in time or manpower. The distance traveled to WC50 also points out the importance of a single snag to a large population of birds. Identification of these primary roosting cavities may be difficult, thus many snags within a particular area are needed to provide suitable roosts. The exceptional use of one cavity also points out the need for more detailed work on the microhabitats of cavities. Each cavity does not provide the same essential habitat requirement~, especially Knorr, O.A. 1957. Communal roosting of the Pygmy Nuthatch. Condor, 59:398-399. LITERATURE CITED Hay, D. 1983. Personal conversation, Department of Biological Sciences, Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ. a 124 Lack, D. 1968. Ecological adaptations for breeding in birds. Methuen, London. Norris, R.A. 1958. Comparative biosystematics and life history of the nuthatches, Sitta pygmaea and Sitta pussilla. Univ. of Cal. Publ. in Zool. 56:119-300. Ward, P., and A. Zahav.i. 1973. The importance of certain assemblages of birds as "information centers" for food finding. Ibis 115:517-534. Weatherhead, P.J. 1983. Two principal strategies in avian communal roosts. American Naturalist 121:237-243.