Acacia Chihuahuan Desert Rangeland M.lshaque R. L. Stei ner

This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain.

Ecology of Two Acacia Species in

Chihuahuan Desert Rangeland

M.lshaque

R. F. Beck

R. L. Stei ner

Abstract-Whitethorn acacia (Acacia constricta Benth) and viscid acacia (Acacia neovernicosa Isely) are drought resistant and winter deciduous shrubs that exhibit sympodial growth patterns. Individual stands of whitethorn acacia and viscid acacia growing in southern New Mexico were evaluated. Measurements were made biweekly for two growing seasons; 1993 had near average rainfall while weather in 1994 was very droughty. The results of the study indicated that both species had lower growth rates in 1994 than

1993 in terms of twig diameter, leaf production, flower and pod production and number of side branches per twig. This difference is attributed to the low rainfall in 1994. Whitethorn acacia had a higher growth rate than viscid acacia in terms of percent increase in twig diameter and number of side branches/twig during both years.

However, viscid acacia twigs produced more leaves, flowers, pods than whitethorn acacia.

Many grasslands in the United States have been changed into shrublands while others have become deserts. In New

Mexico, aggressive shrub invasion has lead to economic losses to the state in the form of desertification, lower livestock production and huge expenditures on eradication of such species (Herbel and Gould 1995). In the Chihuahuan

Desert, the increasing abundance of whitethorn acacia (Aca-

cia constricta Benth) and viscid acacia (Acacia neovernicosa

Isely) are causing various management problems. These shrubs are not considered a serious threat to rangelands by many researchers and managers, and therefore more emphasis has been placed on other shrub species, particularly on creosotebush (Larrea tridentata (DC.) Cov.) and mesquite

(Prosopis glandulosa Torr.). Very little is known about the growth-behavior of these Acacia species in southern New

Mexico. Because of their impending importance on rangelands, there is an immediate and growing need to conduct more research on these shrubs. Through this research the ecological requirements ofthese plants will be better understood leading to better management of Chihuahuan Desert rangeland.

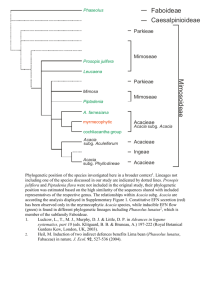

The genus Acacia is part of the Fabaceae family. The members of this genus are found as shrubs or small trees. In deserts Acacia species playa vital role in stabilization and by providing forage for herbivores. In the United States, several Acacia species are found in the Southwest (fig. 1,

Moore 1989).

Whitethorn acacia is an upright or spreading shrub or small tree commonly 1 m to 3 m tall and has a diameter up to 2 m, though larger plants sometimes occur. Bark of twigs is smooth, purple grey to reddish, becoming fissured and grey on older limbs and trunks. The twigs are often armed with paired white spines. The foliage of the plant is cold and drought deciduous (Johnson 1993). Occasionally some limbs of the plant are spineless or often an entire plant may be spineless. Yellow-orange, fragrant ball-shaped flowers dot the foliage. Pods are reddish brown, curved, about 10 cm long, and constricted between the seeds. Its habitats includes washes, gravelly plains, rocky hillsides and dry hills and mesas about 450 to 1,950 m in elevation throughout deserts (Mielke 1993). This species is distributed from Texas to Arizona and Mexico (Hiles 1992). The plant is occasionally browsed by game animals and cattle (Powell 1988) but generally has little forage value. The plant produces HCN under certain conditions (Parker 1972).

The plant has been reported to be used for several different medicinal purposes. The leaves and pods when ground into a powder make an excellent infused tea for diarrhea and dysentery, as well as a strongly astringent hemostatic and antimicrobial wash. The straight powder is used to stop superficial bleeding, and to stop body rashes. The powder is widely used by native Americans for treating the sore backs and flanks oftheir horses. The flowers and leaves as a simple tea acts as a sedative and are a good anti-inflammatory for

I?: Barrow, Jerry R; McArthur, E. Durant; Sosebee, Ronald E.; Tausch,

Robm J., comps. 1996. Proceedings: shrubland ecosystem dynamics in a changing environment; 1995 May 23-25; Las Cruces, NM. Gen. Tech. Rep.

INT-GTR-338. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service

Intermountain Research Station. "

M. Ish~que is Graduate Student and R F. Beck is Professor, Animal and

Range SCIences Department, and R L. Steiner is Assistant Professor

Experimental Statistics Department, New Mexico State University Las Cruces'

NM88003. ' ,

114

Figure 1-Current distribution of Acacia species in southwestern USA (Moore 1989).

stomach and esophagus in nausea, vomiting, and hangovers. The pods of the plant are used for conjunctivitis. The root is thick and mucilaginous and used as a tea is good for sore throats and mouth inflammations as well as dry, raspy coughing (Moore 1989).

Viscid acacia is an open, upright shrub, 2 to 3.5 m tall with a 1 to 3 m canopy spread. New bark has a pink to reddish color. The twigs of the plant are usually armed with paired white spines. The skeletal, open growth habit and sparse foliage provide an untamed appearance. The leaves are small, oily green in color, and are drought and cold deciduous

(Johnson 1993). The entire plant, including the leaves, stems, and pods, are sticky from glandular secretions. The fragrant yellow ball-like flowers are sprinkled throughout the shrub from April to July (Mielke 1993). The plant is generally found at elevations from about 900 m to 1,500 m in desert plains, stream beds, canyons, mesas and rocky calcareous hills Osely 1969) and on shallow caliche and limestone soils on dry slopes (Schmutz et al 1968). The species is distributed from Texas to New Mexico and Arizona, southward into Mexico (Martin and Hutchins 1980).

The major objectives of this study were to determine the growth characteristics and growth rates of these two Acacia species.

Study Area and Methods

In this study 2 different sites, Jornada Plain and lower bajada of Organ Mountains in the Chihuahuan Desert were chosen. The sites were about 12 km apart at an elevation near 1400 m above sea level. On each site one of the two

Acacia species was studied from May to October during 1993 and 1994.

The climate of the area is typical for a continental interior location. Daytime temperature highs in the summer often exceed 35°C with nighttime temperature nearly 15 °C lower.

Freezing temperatures are common in winter. Annual precipitation averages 235 mm (fig. 2). Most summer precipitation comes from localized thunderstorms of high intensity while winter moisture comes from frontal storms producing low-intensity rainfall, occasionally snow. Springs are usually dry and windy.

Whitethorn acacia site was located on the Jornada Plain on the southern side of Dona Ana Mountains about 10 km northeast of Las Cruces, New Mexico. The topography of the site was flat with sandy and clayey soils (fig. 3). On this site, whitethorn acacia was the dominant shrub. Several grass and forb species were present. The most common grasses were tobosa (Hilaria mutica (Buckl.) Benth.) and burrograss

(Scleropogon brevifolius Phil). The site was surrounded by other plant communities dominated by either creosotebush or mesquite plants.

Viscid acacia site was near Tortugas Mountain 2 km east of Las Cruces, New Mexico. This site is part of the lower bajada (with a west exposure) from the Organ Mountains to the Rio Grande flood plain. The study site was located at the top of a ridge with arroyos on both sides. Soils are shallow with little top soil, much of the surface is characterized by desert pavement (fig. 4). Very few herbaceous species grow on this site. Creosotebush communities grow near by.

Figure 3-Site dominated by whitethorn acacia at

Jornada Plain in southern New Mexico .

• Annual

250

200

E

§,150 c

0 la

15.

100

£ .

50

0

1993 1994

Figure 2-Precipitation records of Chihuahuan

Desert in southern New Mexico. Long term records are for 1930-1994.

Long-tenn

115

Figure 4-Site dominated by viscid acacia near

Tortugas Mountain in southern New Mexico.

,

..

~.

.

On each site, 5 small and 5 large acacia plants were randomly selected. For whitethorn acacia, the small plants were <1.0 m tall and the large plants were >2.0 m tall. For viscid acacia, the small plants were <0.5 m tall and the large plants were> 1.0 m tall.

On each plant, 8 twigs (2 from each side of the plant, according to cardinal directions) were selected and tagged.

The various growth parameters of these twigs were recorded every 15 days from May to October in 1993 and 1994. Growth was already initiated before the first sampling period in

1993. Basal diameter of the twigs was measured with a vernier calliper.

Total number ofleaves, mature flowers, green immature pods per twig and side branches were counted at each sampling period. Plant size had little influence on attributes measured, so data presented in this paper are averages across large and small plants. Twigs sampled ranged in length from 100 mm to 200 mm for both species. Twigs grew on the average less than 2 mm during the study. Some twigs lost length because of the tip dying back.

Results and Discussions

Both Acacia species increased in average twig diameter during 1993 (fig. 5 and fig. 6). The average twig diameter for whitethorn acacia increased from 2 mm to 2.95 mm, a 47% increase in twig diameter in that year. For viscid acacia, twig diameter increased from 2.4 mm to 3.0 mm an increase of

25%. During 1994, twig diameter for both species increased very little.

On the average, whitethorn acacia produced 33 leaves/ twig at the peak of its growing season in July 1993. But in

1994, leaf production was only 24 leaves per twig and moreover, leaf growth started later in this year (fig. 7). On the average, 73 leaves per twig were produced on viscid acacia during peak season of its growth in 1993 while only 52 leaves were produced per twig in 1994 (fig. 8). Whitethorn acacia produced by mid June (2nd sampling period of this otameter

In mm

3.1

3.0

2.9

2.8

2.7

2.6

2.5

2.4

5 6

' I '

7 i

I

8

MONTH i i l i i l

9

~1994

, I

10 11

Figure 6-Average diameter of twig for viscid acacia by year. species) in 1993 an average of 10 leaves/twig, while viscid acacia had produced on the average 10 leaves/twig by mid

May (1st sampling period of this species) in the same year.

From this it can be inferred that viscid acacia started its growth about one month earlier than whitethorn acacia in

1993. In 1994, we see a similar trend, the average number of leaves/twig of viscid acacia were near 10 by mid May (1st sampling period), while this number of leaves on whitethorn acacia did not appear until late June, one and a half months later. Neither species leafs-out as early as other shrub species in the area. Both species appear to be well adapted to the environmental extremes which characterize the area. Differences between time of green up may partly be explained by soil texture differences and soil moisture availability.

Total No.

Leavea

40

30

20

6 7 8

MONTH

9

Figure 5-Average diameter of twig for whitethorn acacia by year.

1993

-6-6--es

1994

10 11

10

0

5 6 7 8

MONTH

........ 1993 ~1994

" i i i

9 10

"

11

Figure 7-Average total leaves per twig for whitethorn acacia by year.

116

Total No. l..eave8

80

70

60

60

40

30

20

10

...... 1993

6---t!r-b

1994

0

5 6 7 8

MONTli

Figure 8-Average total leaves per twig for viscid acacia by year.

9 10 11

No. Flowers

& Pods

S

4

3

2

5 6

........ Flower 93

B--9--B

Imm.Pod 93 tr---6-6

Flower 94

+-+-+ Imm.Pod 94

7 8

MONTli

9

Figure 1 O-Average total mature flowers and green immature pods per twig for viscid acacia by year.

10 11

No. Flowers

& Pods

0.30

0.28

0.12

0.10

0.08

0.06

0.04

0.02

0.26

0.24

0.22

0.20

0.18

0.16

0.14

0.00

5 6 7 8

MONTli

9

Figure 9-Average mature flowers and green immature pods per twig for whitethorn acacia by year.

...... Flower 93

B-B-B

Imm.Pod 93

+--+-+ Imm.Pod 94

10 11

Twigs of whitethorn acacia produced very few «1/twig) mature flowers and green immature pods in 1993. But, in

1994, there was almost no production of flowers and pods

(fig. 9). Viscid acacia, on the first sampling date, had 4-5 mature flowers per twig in mid May 1993 which indicates growth had initiated earlier. The number of green immature pods was greatest (3/twig) in early July (fig. 10). The number of flowers and pods declined during the remainder of the growing season. Flower and pod production was lower in 1994, averaging less than 2/twig at all sampling dates.

The twigs of whitethorn acacia on the average produced more side branches than viscid acacia in both years (fig. 11).

This suggests that whitethorn acacia has more buds which may become active if somehow the terminal end of the primary twig is damaged or another possible explanation is

No. Side

Branches

0.9

0.8

0.7

0.6

0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

93

94

VIscid

Figure 11-Average number of side branches per twig on viscid and whitethorn acacia by year.

93 94

Whitethorn

that the growing region on the primary twig does not have as strong a hormonal control over the lateral buds as does viscid acacia. The difference in number of side branches between

1993 and 1994 in figure 11 is the number of new twigs that grew in 1994. For both species, this average increase was near 0.1 per twig.

117

Growth of both species in 1994 was limited by the below average rainfall for several months before initiation of growth and during the summer growing season. This period oflow rainfall was also accompanied by high temperatures.

In 1994, neither species appeared to put much energy into flower and seed production, and twig and side branch growth.

The number ofleaves produced in 1994 was 30% less than in

1993. Neither species showed any stress (wilting) because of low available water.

Conclusions

-------------------------------

Viscid acacia started growth almost one month earlier than whitethorn acacia during both years and both species exhibited sympodial growth pattern.

Whitethorn acacia had a 47% increase while viscid acacia had a 25% increase in twig diameter during 1993 growing season but in 1994, there was no significant increase in twig diameter of these species.

During both years, viscid acacia produced more leaves/ twig than whitethorn acacia.

Whitethorn acacia produced more side branches per twig than viscid acacia during both years.

Overall whitethorn acacia had higher growth rate than viscid acacia.

References

----------~---------------------

Herbel, Carlton H.; Gould, Walter L. 1995. Management of mesquite, creosote bush, and tarbush with herbicides in the northern

Chihuahuan Desert. New Mexico Agriculture Experiment Station Bulletin 775. 53 p.

Hiles, H. T. 1992. An archaeologist guide to Native American use of southwestern plants. Fairacres, NM: Southwestern Research

Native. 572 p.

Isely, Duane. 1969. Legumes of United States: 1. Native Acacia. In:

Sida Contributions in Botany. 3(6): 365-386.

Johnson, Matthew B. 1993. Woody legumes in southwest desert landscapes. Desert Plants. 10(4): 143-170.

Martin, W. C.; Hutchins, C. R. 1980. A flora of New Mexico. Vaduz,

Germany: J. Cramer. Vol. 1, 1276 p.

Mielke Judy. 1993. Native plants for southwestern landscapes.

Austin, TX: University of Texas Press Austin. 310 p.

Moore, Michael. 1989. Medicinal plants of desert and canyon west.

Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico Press. 184 p.

Parker, K. F. 1972. An illustrated guide to Arizona weeds. Tucson,

AZ: University of Arizona Press. 338 p.

Powell, A. M. 1988. Trees and shrubs of trans-pecos Texas. Alpine,

TX.: SuI Ross State University. 536 p.

Schmutz, E. M.; Freeman, B. N.; Reed, R. E. 1968. Livestockpoisoning plants of Arizona. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona

Press. 176 p.

118