VARIABILITY AND DYNAMICS OF SPOTTED OWL NESTING HABITAT IN EASTERN WASHINGTON Richard Everett

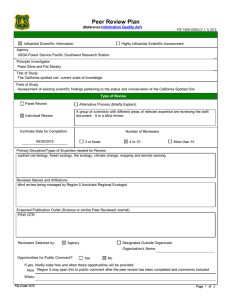

advertisement

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. VARIABILITY AND DYNAMICS OF SPOTTED OWL NESTING HABITAT IN EASTERN WASHINGTON Richard Everett Sandra Martin Monte Bickford Richard Schellhaas Eric Forsman ABSTRACT Corvallis, OR. Dr. Forsman is using radio telemetry to document habitat use and home range of six pairs of spotted owls on the Wenatchee National Forest. This project is part of the Spotted Owl RD&A Program under the direction of Kent Mays and his staff, Pacific Northwest Research Station headquarters, Portland, OR. This preliminary study documented the array of stand conditions associated with six spotted owl nest sites, the character of the neighboring stands, and the disturbance regimes that created current forest structure. Forest structure and cover varied greatly among nest sites and the "neighborhood" stands, but there are areas of commonality in the presence of dense (>70% cover), multilayered canopies, and the presence of Douglas-fir and mistletoe brooms. Silvicultural prescriptions are suggested for the preservation of the spotted owl and associated ecosystems. These prescriptions attempt to mimic the intensity and frequency of processes that have created the current spotted owl habitat. SAMPLING FOREST STRUCTURE AND COMPOSITION The six nest sites occur on the Cle Elum Ranger District, Wenatchee National Forest, in eastern Washington. Five of the six sites supported reproductively successful pairs of spotted owls during the 1989 nesting season. The sixth site was used in 1990, but the nesting attempt was unsuccessful. INTRODUCTION Nest Stand The Wenatchee Forestry Sciences Laboratory and the Wenatchee National Forest have formed an integrated RD&A team to work on the development of forest management practices which create or maintain spotted owl habitat. It is our belief that, through the creation of additional or enhanced spotted owl habitat, we will be able to better preserve the owl and retain timber harvest options. Our approach is to build a biologically sound foundation for the development of silvicultural prescriptions. This will be achieved by (1) defining the current forest structure of nest stands and adjacent neighborhood stands occupied by reproductively successful spotted owl pairs, (2) examining past formative events-natural and human induced-that created the current spotted owl habitat, and (3) developing silvicultural prescriptions that maintain desirable habitat components or create new spotted owl habitat where it currently does not exist. This paper reports on our initial study of six spotted owl nest sites in the eastern Cascades in a coordinated project with Dr . Eric Forsman, Pacific Northwest Research Station, At each nest site, a l/lO-acre circular plot was centered on the nest tree. All trees greater than 4.5 ft in height, and with DBH ~ 1 in. were recorded for species, DBH, and height. Age was determined for trees with DBH > 2 in. Species, diameter, length, and decay stage were recorded for each stump and log. Crown closure was measured with a densimeter. A l-chain-wide transect was placed in the nest tree stand and a search made for evidence oflogging, road building, and fire. Forest Service documentation of logging history and onsite data collection were used to ascertain the logging histories of these sites. Increment borer tree cores or wedges were taken from six to eight trees, snags, or stumps having fire or logging damage scars to date time of disturbance (Arno and Sneck 1977). Spotted Owl Neighborhoods Nest stands are part of a patchwork of diverse forest communities across the landscape that make up the home range of the spotted owl. Owl telemetry location points provided by Dr. Forsman showed that approximately 90% of the owl observations during the 1989 breeding season could be captured in a 1,000- to 1,200-acre area surrounding the nest stand. We defined this portion of the home range around the nest site as the "neighborhood." Paper presented at the National Silviculture Workshop, Cedar City, UT, May 6-9, 1991. Richard Everett is Science Team Leader; Sandra Martin is Research Wildlife Biologist, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Wenatchee, WA; Monte Bickford is Silviculturist; Richard Schellhaas is a Forester, Wenatchee National Forest, Wenatchee, WA; Eric Forsman is a Wildlife Biologist, Pacific Northwest Research Station, Corvallis, OR. 35 Previous research on spotted owl ecology has shown that owls prefer older, denser stands, they avoid clearcuts, and are neutral to intermediate stand conditions (Carey and others 1990). Stand polygons within the neighborhood were identified by < or > 40% cover, single- or multiple-canopy layer, and the presence of trees >11 in. DBH. Stand types were delineated within four of the six spotted owl neighborhoods on 1986 aerial photographs (Scale 1112000). Stands do not meet the current definition for live tree "old growth" because of the scarcity of trees greater than 30 in. in diameter (U.s. Department of Agriculture 1986). Our closest approximation to old-growth stands is that portion of Class 8 with greater than 70% crown canopy. Table 1-Stand characteristics at six spotted owl nest sites on the Wenatchee National Forest, WA Site Porky Basin Hurley Creek Ba~(er/Mill Snow/Boulder Taneum" Gooseberry Avg. all sites Trees in the 60- to 100-year age classes were most numerous, but numbers varied greatly among sites (fig. 1). The distribution of numbers of trees in each 2-in.-diameter class similarly varied among sites (fig. 2). When trees ~20 in. are totaled on the plots, we find 0, 1,2,3,4, and 9 trees in this (years) Maximum II of tr••• p.r plot 80,-----------~~----------------------~ 60 ............................ . .............................................................. . 40 ............................ . .................................................................... . 30 ........................... . 20 10 O~~--~~--LJ-c~~L-~~~~~~~~~ 80 80 100 12(; 140 180 180 200 220 240 280 280 380 Age Classes Data from 8 .it•• _Max 1110 u --Mean plol (Ir . . . , 4.1i II I.") Figure 1-Age class distribution for trees located adjacent to the nest site. 8 10 12 14 18 18 20 22 24 28 28 3032 34 38 3840 42 Diameter Classes Pine _ Douglas-fir Percent Ft2/acre Ft1 In. 92 93 95 93 95 88 93 190 200 250 210 270 200 220 23 30 38 53 67 29 3.9 44 4.8 7.2 8.1 10.1 5.9 6.7 Our preliminary study of nest sites showed that repeated fires occurred in these stands. Fire occurrence averaged 13 years prior to 1900 (fig. 3). After 1900, fire frequency increased to 18 to 20 years ontwo sites, and no fire scars were found on the remaining sites. Prior to fire suppression, the ground fires appeared to maintain an open forest on the sites (fig. 4). After fire suppression was initiated in the early 1900's, rapid stand development occurred. Logging replaced fires as the primary disturbance some 60 years ago. Stands without fire disturbance have gotten denser, accumulated large amounts of biomass, and developed a dense tree understory of primarily grand fir (fig. 2). Fires that occur in stands with heavy fuel loads on the Wenatchee National Forest are now stand-destruction fires that can cover 50,000 to 200,000 acres and which have destroyed spotted owl habitat. In the 1970's, heavy western spruce budworm defoliation hit the Forest. Although aerial spraying reduced budworm populations to endemic low levels, the long-term solution 100 E222l Ponderosa Average diameter DISTURBANCE REGIMES Percent of all trees by diameter cia.. 2 4 6 Average height size class among sites. The average tree diameter for the sites is low (6.7 in.), but this is influenced by the high percentage of the trees in sapling and pole-size classes (table 1). When these trees are removed from the calculations, the average tree diameter more than doubles for all sites. Height exhibited even greater variability among the sites. The range of heights was greatest in the lower height classes, but some variability was also found in midlevel classes. Average height for only those trees ~6 in. DBH was roughly double that found for all trees on the site ~4.5 ft tall. Maximum age on the sites showed a wide range, from 128 to 368 years. The average age for trees ~6 in. DBH was roughly 50% greater than for all trees ~4.5 ft tall. Species composition did not vary greatly among the sites. Grand fir dominated, but Douglas-fir was always present and usually represented in the larger, older classes of trees (fig. 2). Total basal area, and particularly crown density, did not exhibit the variability found with the other stand characteristics. Crown density was highly consistent, and considering the range of tree diameters and heights at these six sites, this consistency is notable. Tree Age 40 Total basal area lAverage from all trees >4.5 ft tall on a lho-acre circular plot, centered on nest tree. NEST STAND FINDINGS 20 Crown density ~ Grand fir Figure 2-Distribution of all trees by species and diameter class adjacent to the nest stand. 36 SPOTTED OWL NEST STANDS CV values for other habitat classes suggest that at least a portion (26 to 36%) of the neighborhood is currently very heterogeneous in cover and stand structure. FIRE FREQUENCY (13 YR. AV. PRE 1900 ) ON YEARS) VRS DEVELOPING SILVICULTURAL PRESCRIPTIONS FOR NON·HCA AREAS 2a~---------------------------------- 20 20 -.-.- .... ----.-.- - .......................... -.- .. --.-- .......... -....... ·18-···-· .. 1A_ ................................. _.•• _•...... _.......••••. 12 11 16 10 Based on our preliminary information on current stand and neighborhood characteristics and the knowledge of how these stands developed, the Wenatchee National Forest proposes to use tree harvest to create and maintain owl habitat as required. The Forest is also required to follow the 1976 National Forest Management Act (U.S. Department of Agriculture 1983) that states "all forested lands in the National Forest System shall be maintained in appropriate forest cover with species of trees, degree of stocking, rates of growth, and condition of stands designed to secure the maximum benefits of multiple-use sustained yield management in accordance with land management plans." The Wenatchee National Forest developed a broad landscape-level philosophy, "diversified age" management, to maintain the landscape-level legacy of past harvest and fire regimes. This management philosophy specifies a wide range of silvicultural cutting methods to produce and maintain diversity of tree species and stand types. Selective timber harvest scenarios to preserve the integrity of the neighborhood and the mosaic of stand types is preferable to custodial management where fuels buildup may lead to large stand replacement fires. A silvicultural prescription, "full stocking control," has been developed for forest situations dominated by a mosaic of small stands. The key ingredient is reduction of overstocking by removing those trees least likely to survive and grow at acceptable rates. Emphasis is also on maintaining or increasing the fire-tolerant species, especially ponderosa pine, western larch, and Douglas-fir. Maintaining Douglasfir may be critical to providing spotted owl habitat as all spotted owl nest sites on the Wenatchee National Forest occur where at least some Douglas-fir is present. Without the removal of a significant portion of canopy, Douglas-fir is likely to be replaced by more shade-tolerant grand fir (fig. 2). The Wenatchee Forest Plan recognizes this problem and prescribes an "extended shelterwood" system for managing spotted owl habitat. This system uses a 130-year rotation, leaving approximately 20 trees per acre until age 260 years. This prescription will maintain stand productivity, reduce wildfire hazard, and retain components of "old growth" forest. This prescription also provides for dispersal cover for owls as recommended by the 50-11-40 rule of the Interagency Scientific Committee Report (Thomas and others 1990). Where spotted owl habitat exists, the report recommends that 50% of the area be in stands with trees greater than 11 in. DBH and with 40% crown cover. Prescribed tree removal from spotted owl habitat may be required to safeguard these sites from wildfire that would degrade stands to below the 50-11-40 rule. The occurrence of mistletoe may increase silviculture options if mistletoe brooms provide spotted owls with platforms required for nesting and raising young. Platforms 5 --;--···_·Y/1 HURLEY PORKY 1_ PRE BAKER SNOW f2Zj 190G-19DO 1iOO GOOSE I PORKY.SAKER,aNOW (NO FIRE!! AFTER '1001 Figure 3-Fire frequency in five spotted owl nest stands. HURLEY CREEK TREE AGE AND FIRE HISTORY TREES I ACRE 70r-------------------------------------~ 60 --- .... --.----.--.- _.----.---- ... «e- ... -- .. --..... -------- -.. --.-. F F F FFF F F F F 50 40 L L L 50 LOGGING 100 150 L YEARS BEFORE 1990 I ~ TREES PER AGE CLASS 200 250 I F FIRES '(10 ye.r .ge cl .....1 Figure 4-Tree age and fire history on a spotted owl nest site. was to restore earlier successional species through regeneration cutting. The combination of fire, insect damage, logging, and irregular topography has created a diverse mosaic of stand conditions in spotted owl neighborhoods on the Wenatchee National Forest. NEIGHBORHOOD ANALYSIS Spotted owl neighborhoods are a complex array of stand types (fig. 5). Using the eight potential owl habitat classes, the mean number of polygons was 42 (SD = 8) with an average size of31 acres (SD = 10). A majority of the acreage (mean =858 acres, SD =86) is in Class 8 habitat, with multilayered canopy, trees >11 in. dia., and greater than 40% canopy cover. Other habitat classes combined had less total acreage (mean = 69 acres, SD = 56) and these were divided among a greater number of polygons. The coefficient of variation (CV) for acreages of specific owl habitat classes among the neighborhoods varied from 6 to 178%. At 6%, habitat Class 8 had the lowest CV. The high 37 HABITAT _ <40X SWALL SINGLE CIJ <40X lIT]] SNALL NULTI <40" LARGE SINGLE rnm <40X LARGE NUL TI o >40" SMALL SINGLE _ >40" SNALL MULTI 111>40" LARGE SINGLE ~>40" LAR.GE NULTI Figure 5-Habitat polygons for four spotted owl neighborhoods. Polygons were classified by < or > 40% canopy cover, small vs. large trees « or > 11 in. DBH), and single vs. multiple canopy layers. Neighborhoods are 1,000 to 1,200 acres in size. suggests some flexibility in creating owl habitat in the eastern Cascades. The following prescriptions are adapted to eastside forest conditions and are consistent with the Committee's generalized silviculture treatments for manipulating forest structure. Shelterwood cuttings, leaving an average of 20 of the largest full-crowned trees, is a preferred regeneration method. This will create a two-storied stand similar to what we found at nest sites we examined in this study. In stands where Douglas-fir is present, the target should be at least six trees per acre of this species. Residue removal levels need to be moderate to provide sufficient down woody material as habitat for prey species, but not enough to create an excessive fire risk. Desired fuel loading should be in the range of 10 to 30 tons per acre. Intermediate harvests that remove only the annual accumulation of biomass and maintain multilayered canopy conditions are recommended. This would allow remaining trees to more rapidly reach larger diameter classes. For example, if we entered on a 15- to 20-year interval, and our stands are growing 60 cubic feet per year/acre, we can occur in large, defective trees with cavities or broken tops or trees of an array of sizes that contain large mistletoe brooms. Our nest site studies have shown that spotted owls will nest in mistletoe brooms in trees as small as 12 in. DBR. Owls have successfully nested in stands with few large trees when mistletoe brooms were present; however, the long-term impacts of different nesting conditions on spotted owl reproductive success are not yet known. Management for mistletoe brooms may allow for the more rapid creation of components of owl habitat in younger and smaller trees than in stands without mistletoe. RECOMMENDED SILVICULTURAL TREATMENTS The Interagency Scientific Committee Report (Thomas and others 1990) recommended several silvicultural approaches for mitigating harvest impacts on current and future owl habitat. The wide array in tree sizes present at the nest sites (fig. 6) and mosaic of neighborhood stands 38 SPOTTED OWL NEST SITES scenario for spotted owl habitat appears appropriate, but rather we found an array of nest stand and neighborhood conditions associated with six pairs of owls. From our preliminary investigation, we can conclude that spotted owl habitat at these six sites is variable in stand structure under the canopy, but that canopy cover is consistently high, and that stand composition is also fairly consistent. Much of the spotted owl neighborhood does not meet the currently accepted criteria of old growth, but a majority of stands had multilayered canopy, greater than 70% crown cover, and had trees >11 in. DBH present. The neighborhood and surrounding landscape provide a mix of contiguous, dense, multilayered stands and highly diverse, small polygons. We hypothesize this mix of stands meets the requirements of the owl and provides the habitat necessary to support a variety of prey species throughout the year. Although the neighborhoods we examined were selected by nesting owls, the ultimate measure of habitat quality must be the ability of the landscape to support a portion of a viable population. Investigating the long-tenn quality of forest neighborhoods surrounding spotted owl nests in eastern Washington will require a minimum of 5 to 6 years of demographic data on resident owls. The amount of variation in stand types within neighborhoods suggests many silvicultural treatments may be possible and perhaps required to maintain stand diversity. Silviculture may provide an opportunity to improve stand structure for owl habitat more rapidly than would occur by natural processes alone. The forest is dynamic; current nest stand and neighborhood characteristics are the result of past natural and human-induced disturbances. Further changes in current spotted owl nest stands and neighborhoods can be anticipated with or without the application of future silvicultural prescriptions. We believe that the full range of potential silvicultural options-from no intervention in natural succession to clearcutting of specific stands-will have a role in perpetuating northern spotted owl habitat in eastern Washington forests. TREES) 11- DIA. TREEIAC HURLEY PORKY BAKER 8NOW GOOSE l7\NEUM _NEST 8'QND A /tIf!... ea TRI!!lAC. [RANCII! ,.-111) SPOTTED OWL NEST SITES TREES ) 21- DIA. TREE/AC HURLEY PORKY BAKER SNOW GOOSE l»oIEUM _NEST STAND B /tIf!... , . TIU!!lAC. [RANGI! 1t-3U Figure 6-Numbers of trees greater than 11 and 21 in. DBH at each nest site. could remove 900 to 1,200 cubic feet. This approximates the level of harvest several of the examined nest stands have sustained for up to 60 years. Objectives would be to maintain full stocking of about 60 trees per acre (fig. 6A), 40% or greater crown cover, and a mix of species including early seral, fire-resistant trees. This prescription would increase stem growth rates and provide conditions more suitable for long-term site protection from fire and disease. Some stands with an array of species could be maintained in a steady-state condition using periodic 15- to 30-year removal entries. Others would eventually need stand regeneration to simulate the fires that kill the fire-intolerant species and leave a few large shelterwood trees of the firetolerant species. A combination of silvicultural practices that maintain a mix of steady-state and regeneration conditions across the landscape appears most appropriate. The steady-state component would maintain the integrity of current owl habitat, and the regeneration component assures continued neighborhood patchiness. REFERENCES Arno, S.F.; Sneck, K.M. 1977. A method for determining fire history in coniferous forests of the mountain West. Gen. Tech. Rep. INT-42. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intennountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 28 p. Carey, A.B.; Reid, J.; Horton, S. 1990. Spotted owl home range and habitat use in southern Oregon coast ranges. Journal of Wildlife Management. 54: 11-17. Thomas, J.W.; Forsman, E.D.; Lint, J.B.; Meslow, E.C.; Noon, B.R.; Verner, J. 1990. A conservation strategy for the northern spotted owl. Report of the Interagency Scientific Committee to address the conservation of the northern spotted owl. 427 p. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1983. The principal laws relating to Forest Service activities. Agric. Handb. 453. Washington, DC: Forest Service. 591 p. U.S. Department of Agriculture. 1986. Interim definitions for old-growth Douglas-fir and mixed-conifer forests in the Pacific Northwest and California. Res. Note PNW-447. Portland, OR: Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. SUMMARY Spotted owl nest stands and neighborhoods we examined are diverse in vegetative cover and structure. No one 39