EROSION AND SITE PRODUCTIVITY IN WESTERN-MONTANE FOREST ECOSYSTEMS Walter F. Megahan

advertisement

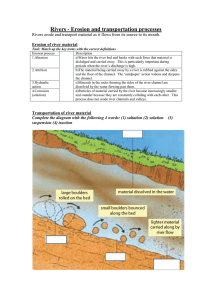

This file was created by scanning the printed publication. Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain. EROSION AND SITE PRODUCTIVITY IN WESTERN-MONTANE FOREST ECOSYSTEMS Walter F. Megahan Washington) established a policy dealing with soil productivity and erosion: ABSTRACT Soil loss from erosion affects site productivity by reducing the nutrient pool and water-holding capacity of the soil and by direct damage to vegetation. The effects of erosion depend on the type of erosion processes because of differences in the depth and areal extent of soil loss, the downslope rate of soil movement, and the probability of redeposition of eroded material. The most severe and longlived site productivity losses occur from debris avalanches and gullying. Forest management practices can increase erosion rates, but wildfires have the greatest potential to accelerate erosion. Erosion increases following fire are directly proportional to fire intensity. Debris landslides and gullying cause serious and long-term reductions in site productivity, but the areas affected are small. Surface erosion occurs over much larger areas and does tend to reduce site productivity, but the magnitude of the reduction is poorly defined because of the compounding effects of compaction on logged areas and water repellency on burned areas. Methods to better assess the erosional effects of forest management on site productivity require a combination of controlled bioassay studies and growthsimulation models. ... to plan and conduct land management activities so that soil loss from accelerated surface erosion and mass wasting caused by these activities will not result in an unacceptable reduction in soil productivity and water quality (Howes 1988). Swanson and others (1989) provide an overview of the effects of erosion on long-term site productivity in the Pacific Northwest. However, their work stresses the results of studies in the Coast and Cascade Ranges in Washington and Oregon. The present discussion concentrates on erosion processes and resulting impacts on site productivity in the interior West, described in this symposium as the western-montane zone. The purpose of this paper is to: describe the potential effects of erosion on productivity, consider how the different erosion processes occurring on forest lands relate to these effects, and summarize the few available published reports documenting the magnitude of the reductions in site productivity associated with erosion in the western-montane region. EROSION EFFECTS ON PRODUCTIVITY INTRODUCTION The effects of erosion on site productivity result from a change in the total depth of soil material at a site or direct damage to vegetation. Changes in soil depth can affect productivity by changing the total nutrient pool and by changing the water storage capacity. Direct damage to vegetation is manifest by changes in mechanical support, changes in the availability of propagules, and direct damage to trees. I use the term "change" in describing the factors influencing site productivity because the reductions in productivity that occur at the site of erosion may be accompanied by increases in productivity at downslope deposition sites. This is especially true in forested settings where slope irregularities and large volumes of surface debris may cause deposition of eroded material within short distances downslope. For example, within the first 4 years after construction, over 95 percent of the material eroded from roadfills is deposited within 20 meters downslope from the bottom of the roadfill on granitic slopes in Idaho (Megahan 1984). Thus, it is important to recognize that the actual effects of erosion on productivity are represented by the net differences in productivity that occur at both erosion and deposition sites. The relative amount of soil loss and deposition depends on the type of erosion processes acting in the area and will be discussed in more detail later. Erosion is a geomorphic process that is a natural component of any forest ecosystem. However, erosion rates can be accelerated by both natural and human disturbances. Wildfire is the most common cause of accelerated erosion in the "natural" forest. Forest management activities, especially timber harvest and road construction, have been shown to increase erosion rates on forest lands. Megahan (1981) summarized the results of 30 studies documenting the effects of fire and forest management practices on erosion rates in the western-montane region. To date, the largest concern with accelerated erosion in relation to forest management has been directed at the resulting downstream sedimentation and accompanying damage to beneficial uses of water. However, concern about the onsite impacts of erosion on forest lands is increasing. The Pacific Northwest Region of the Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture (Oregon and Paper presented at the Symposium on Management and Productivity of Western-Montane Forest Soils, Boise, ID, April 10-12, 1990. Walter F. Megahan is Research Hydrologist, Intermountain Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Boise, ID 83702. 146 EROSION PROCESSES Table 1-Mean horizon thickness, plant-available water, and nutrient content for four granitic soils in the Idaho Batholith (Clayton 1990) 0 Parameter Thickness (cm) Available water (percent by volume) Range in K, Ca, Mg, N, P, S (percent of total) Average K, Ca, Mg, N, P, S (percent of total) 3 82-93 88 The actual impacts of different erosion processes on site productivity are influenced by: (1) the depth of erosion (determines the amounts of soil components that are lost from the site), (2) the areal extent of the erosion (determines the area over which the losses occur), (3) the downslope rate of movement of eroded material, and (4) the probability of redeposition of the eroded material at downslope locations. Relative rankings of these four factors for each of the erosion processes described later are given in table 2. Evaluation of the total effects of erosion on site productivity must consider the net effects of all these factors. Horizon A C 25 11.3 4-11 9 46 4.1 1-7 3 The data in table 1 summarize the average total nutrient pool and plant-available water for four granitic soils in the Payette River drainage of Idaho. Note the large decreases in available water and nutrients with depth. The depth of erosion is important in terms of what is limiting at a site. If nutrients are limiting, loss of only 1. 7 cm of surface organic matter will remove 50 percent of the total nutrients on the site. If water is limiting, as may often be the case in the western-montane area with hot, dry summers, all of the organic horizon and 17 cm of the A horizon must be eroded to remove 50 percent of the site's water-holding capacity. Direct damage to trees caused by erosion occurs frequently in the interior West. Erosion may be severe enough to expose roots, reducing growth rates or reducing mechanical support to the point that the tree falls or is blown over by wind. Such damage can occur from erosion of surface soils (Carrara and Carroll 1979) but is especially prevalent on slopes adjacent to roadcuts due to rapid erosion of the steep roadcut surfaces (Megahan and others 1983). Tree fall caused by lateral erosion of roadcuts is a major concern for road engineers responsible for the maintenance of roads on steep slopes. Additional direct damage to vegetation is attributed to loss of propagules as surface soils are eroded. Seeds, root stock, and sometimes entire plants may be damaged or displaced by erosional processes. Finally, direct damage to large trees may occur from tilting, splitting, or abrasion of the trunks or by burying the lower portions of the trunk. Surface Erosion Surface erosion is defined as the movement ofindividual soil particles by a force. Major factors regulating surface erosion include: soil cohesion, slope gradient, slope length, rainfall intensity, soil infiltration rate, and the amount of ground cover protecting the soil surface. Four different types of surface erosion processes are recognized and all are common in the Intermountain West. They are: splash, ravel, rills, and gullies. Splash erosion is caused by the impact of raindrops and occurs anywhere mineral soils are exposed. Splash erosion is most important on noncohesive soils. Ravel (sometimes called dry ravel or dry creep) occurs on steep slopes, generally over 60 percent, where gravity forces exceed the cohesive forces holding individual soil particles in place. It occurs during dry periods, primarily under the influence of wind, and is most common on noncohesive soils on bare roadfills and roadcuts and on natural slopes where logging, fire, or both, have exposed mineral soils. Rills and gullies (usually defined as rills more than 30 em deep) are caused by channelized overland flow. Such flow is relatively rare on forest soils, even when bare, except where infiltration rates have been reduced by compaction, such as on skid trails or roads, or in the case of severe soil damage and the formation of water repellency as occurs on intensely burned areas. Table 2-Properties of the different types of erosion processes Erosion process Depth of erosion Areal extent Rate of movement Probability of slope storage Surface erosion Splash Ravel Rilling Gullying mm-cm mm-cm cm cm-m widespread localized localized concentrated m/yr m/yr-m/sec m/day-m/sec m/day-m/sec high high moderate low Mass erosion Creep Earthflow Slump Debris slide Debris flow soil depth m-m x 10 m-m x 10 cm-m cm-m widespread localized localized concentrated concentrated mm/yr cm/yr-m/yr m/yr-m/day m/sec m/sec high moderately high moderate moderately low low 147 Debris types offailures include debris slides and flows and involve the surface soil mantle sliding over the underlying bedrock or parent material. Lengths are long relative to their depth (by a factor of 20 times or more) and widths are generally small (meters to tens of meters). Debris failures occur on steep slopes usually greater than 60 percent. Slope depressions that serve as water accumulation zones are the most common sites for the initiation of debris failures. The release of the failures is sudden and movement rates are rapid with velocities of meters per second. Downslope delivery is relatively high, especially for debris flows, because of the high water content of the slide material. The primary factors affecting debris failures are: soil strength, vegetation roots, slope gradient, groundwater depth, and soil depth. Of these, vegetation roots, groundwater depths, and slope gradients (in the case of forest roads) are sensitive to forest management practices. Debris failures have a severe impact on productivity at the site offailure because of the sudden, total loss of the soil mantle. Additional erosion sometimes occurs as a result of scour as the rapidly moving mass of eroded material moves downslope and from subsequent surface erosion in the slide site. However, the area affected is small because of the concentrated nature of the failures. Megahan and others (1978) collected data on 629 landslides in the Clearwater National Forest in Idaho. For a 3-year study period, the total area affected by landslides amounted to 16.5 ha, about 0.003 percent of the total non wilderness area of the forest. Wildfire can increase the number of debris failures per unit area of forest land. Jensen and Cole (1965) reported a total of 34,000 cubic meters of soil loss from the 400-ha Poverty Burn on steep slopes in the South Fork of the Salmon River as a result of debris failures. Assuming an average soil depth of 0.6 meters (reasonable for steep slopes in this area), this volume of soil loss would indicate that about 2 percent of the burn area was affected by debris failures. Although three orders of magnitude greater than the percentage of land affected by mass failures on the Clearwater National Forest, the loss of productivity occurred only on 2 percent of the Poverty Burn, a relatively small area. Expressing productivity loss on the basis of area affected by debris avalanches can be misleading. This is because failure sites are usually located in slope depressions that serve as both soil and water accumulation zones. Because of greater soil depth and increased water availability, such sites also tend to be some of the better sites for tree production. Thus, total site productivity loss may greatly exceed the percentage of area affected by debris failures. In general, surface erosion rates are greatly influenced by the amount of vegetative cover and forest litter that are available for protection of the soil surface. Road construction and wildfires generally cause the greatest reductions in vegetative cover protection and thus commonly result in the greatest increase in erosion rates. However, even on roads and burned areas, erosion rates may decrease rapidly over time as revegetation occurs. Megahan (1974) found road erosion rates on granitic soils decreased about 90 percent by the second year after construction. Similar recovery was recorded about 2 years following a wildfire on a clearcut north slope in granitic soil (Megahan and Molitor 1975) but not following a controlled burn on a clearcut south slope in the same vicinity. In the latter case, considerable active erosion was still occurring 10 years after disturbance (Megahan 1990). Wildfire can cause greatly accelerated surface erosion. Connaughton (1935) evaluated the degree of accelerated surface erosion on an 18,000-ha wildfire in southern Idaho. Accelerated erosion was found on 42 percent of the area on cutover lands and on 28 percent of virgin forest land. In addition to the effects oflogging on erosion severity, there were large increases in the severity of erosion with increasing hillslope gradient and burn intensity. Of all the erosion processes, splash erosion is most widespread since it can occur anywhere bare soil is subjected to raindrop impact. However, the average depth of soil loss and the downslope rate of movement of eroded material are small. Thus, even though large volumes of soil may be moved by splash erosion, the total effect on forest site productivity is low. In contrast, gullying results in the rapid removal of considerable depths of material and transports that material long distances, usually to the nearest stream channel. In this case, productivity is greatly reduced by gully formation. Gullies normally occupy a very small area so the net reduction in productivity for the forest site is again small. Mass Erosion Mass erosion is defined as the movement of many soil particles en masse, primarily under the influence of gravity, and occurs when shear stresses exceed shear strength. Unlike surface erosion, which progresses from the surface downward, mass erosion usually includes the entire soil mantle and often part of the underlying parent material as well. The five major kinds of mass erosion include: creep, earthflow, slump, debris slide, and debris flow (table 2). Creep involves imperceptibly slow (mmlyr) downslope movement of the soil mantle under the sustained influence of gravity on steep slopes. Effects on productivity are essentially nonexistent. Earthflow and oftentimes slumps tend to be deep-seated types of slope failures with the movement plane usually well beneath the soil in the underlying parent material or bedrock. Earthflows and slumps move meters to tens of meters per year and can cause direct damage to trees by tilting and splitting. Aside from road construction, effects of forest management activities on slumps and earthflows are not well defined. STUDIES DOCUMENTING EROSION EFFECTS The effects of debris types of landslides where the entire soil mantle is lost all at once are relatively clear. Severe reductions in productive capacity occur until new soils accumulate at the slide sites. Smith and others (1986) reported a 70 percent reduction in conifer productivity 148 ,.,:,:.' The latest version of the model (FORCYTE-ll) appears to have promise for evaluating the effects ofa number of components of the site-productivity question including the effects of erosion (Kimmins and others 1988). However, HB studies specifically designed to evaluate the effects of soil erosion alone are still needed to validate the model. Klock (1982) developed an interesting alternative to the historical bioassay approach. He used a greenhouse bioassay technique to assess the effects of various amounts of erosion on four different forest soils in central Washington. Soil samples were collected from depths of 0-30 cm, 3-30 em, 7.5-30 cm, and 15-30 cm to simulate respective erosion amounts of 0,3, 7.5, and 15 cm. Growth of ponderosa pine, Douglas-fir, lodgepole pine, and orchard grass (Dactylis glomerata L.) in pots was used to index the effects of erosion. At the end of varying lengths of time, the vegetation was clipped at the soil level and ovendried and weighed. Erosion effects were evaluated by comparing the percentage of vegetation weight for the various eroded soils to that for the uneroded soil. Productivity losses ranged from none to as high as about 85 percent depending on the type of soil, the amount of erosion, and the type of vegetation. Klock (1982) concluded that, although the procedure does not provide a true measure of productivity loss from erosion, it does provide a means to compare the relative effects of different sites and erosion rates and to evaluate the sensitivity of different types of vegetation. on slide sites in the first 60 years and about 50 percent at the end of 80 years on slides occurring on the Queen Charlotte Islands, British Columbia. A gradual increase in productivity is expected for subsequent rotations. No such data have been collected for slides occurring in the interior West. However, personal observations of slide scars in the region suggest that the magnitude and duration of productivity losses are at least as great as those reported by Smith and others (1986). Aside from the formation of gullies, which would appear to have effects on productivity similar to those of debris failures, the effects of surface erosion processes on productivity are much more difficult to evaluate. On logged areas, other factors often associated with or causing erosion, including soil displacement and compaction by timber harvest equipment (Froehlich 1988) and the formation of water-repellent soil layers on burned areas (DeBano and others 1970), can also adversely affect productivity. Thus, studies of effects of timber harvest or fire on productivity have not clearly isolated the effects of surface erosion alone. Clayton and others (1987) showed that the degree oflateral soil displacement was associated with decreased tree diameter and height following logging oflodgepole pine (Pinus contorta Engelm.) and ponderosa pine (Pinus ponderosa Laws.) in central Idaho. Tree diameter (breast high) was reduced an average of 21 percent going from slight to high soil displacement; tree height was reduced an average of 24 percent. In this case, one might assume that the displacement effect would be a good indicator of erosion effects even though the displacement was not entirely caused by erosion. However, they also reported that tree diameter and height in the same area decreased an average of 19 and 18 percent, respectively, with increasing penetrometer resistance, an index of increasing compaction. Thus, it is impossible to discriminate between the negative effects of compaction and soil loss. Smith and Wass (1980) reported reductions in the height growth of Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii [Mirb.] Franco) on logging skidroads on sensitive sites in interior British Columbia. But again, it was impossible to isolate the effects of erosion alone. Because of confounding effects of other factors affecting productivity, it appears unlikely that it will be possible to accurately assess the effects of surface erosion on productivity based on field observations of tree growth in timber sale areas. Such studies are referred to as historical bioassay (HB) studies (Kimmins and others 1988). Also, HB approaches are based on observations for the growth conditions that existed during the life of the vegetation. Using the results of such studies for prediction purposes requires the assumption that the soil and atmospheric resources remain static. Such an assumption is open to question, especially at present when concerns for global climate change are widespread. Process models of vegetation growth processes offer an alternative for evaluating effects of erosion but have limitations primarily because of intensive input data requirements (Kimmins and others 1988). A hybrid simulation model called FORCYTE combines the best features of both HB and process model approaches while minimizing some of the problems. CONCLUSIONS Erosion can cause large decreases in forest productivity at the site of soil loss. Reductions in productivity are directly, but not linearly, proportional to the depth of soil lost. The greatest and longest duration (decades) impacts are caused by debris landslides and gullies. Both landslides and to a lesser extent gullies are cOllcentrated in small areas that tend to be soil and water accumulation zones. Such areas also tend to be relatively high in site productivity, so the percentage of loss of productivity exceeds the small percentage of the area affected by the erosion. Surface erosion removes much less total depth of soil than mass erosion, but may have a greater shortterm impact on productivity because larger areas are affected. However, surface erosion rates tend to decrease rapidly over time (a few years) so the long-term effects are limited. Erosion rates are minimal in the undisturbed forest but can be greatly accelerated by natural or man-caused disturbances. Of the various types of disturbances, wildfire has the largest potential for reducing productivity because of large soil losses over broad areas. Except for landslides and gullies, the erosional consequences of forest management activities are difficult to evaluate because of the confounding effects of other types of site disturbances. Considerable research, including both bioassay and process modeling techniques, is needed to better quantify the effects of erosion on site productivity. Studies need to consider the net effects of both on-site soil loss and downslope deposition of eroded material. 149 REFERENCES Spec. Publ. 45. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy: 53-66. Megahan, W. F. 1974. Erosion over time on severely disturbed granitic soils: a model. Res. Pap. INT-156. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 14 p. Megahan, W. F. 1981. Effects of silvicultural practices on erosion and sedimentation in the interior West--a case for sediment budgeting. In: Baumgartner, D. M., ed. interior West watershed management: Proceedings of the symposium; 1980 April 8-10; Spokane, WA. Pullman, WA: Washington State University, Cooperative Extension: 169-181. Megahan, W. F. 1984. Data on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Boise, ID. Megahan, W. F. 1990. Data on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Boise, ID. Megahan, W. F.; Day, N. F.; Bliss, T. M. 1978. Landslide occurrence in the western and central northern Rocky Mountain physiographic province in Idaho. In: Youngberg, C., ed. Forest soils and land use: Proceedings, North American forest soils conference; 1978 August; Fort Collins, CO. Fort Collins, CO: Colorado State University: 116-139. Megahan, W. F.; Molitor, D. C. 1975. Erosional effects of wildfire and logging in Idaho. In: Watershed management symposium; 1975 August 11-13; Logan, UT: 423-444. Megahan, W. F.; Seyedbagheri, K. A.; Dodson, P. C. 1983. Long-term erosion on granitic roadcuts based on exposed tree roots. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms. 8: 19-28. Smith, R. B.; Wass, E. F. 1980. Tree growth on skidroads: on steep slopes logged after wildfires in central and southeastern British Columbia. BC-R-6. Victoria, BC: Environment Canada, Canadian Forestry Service, Pacific Forest Research Centre. 28 p. Smith, R. B.; Commandeur, P. R.; Ryan, M. W. 1986. Soils, vegetation, and forest growth on landslides and surrounding logged and old-growth areas on the Queen Charlotte Islands. FishIForestry Interaction Program. Land Manage. Rep. 41. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Forests. 95 p. Carrara, P. E.; Carroll, T. R. 1979. The determination of erosion rates from exposed tree roots in the Piceance Basin, Colorado. Earth Surface Processes. 4: 307-317. Clayton, J. L. 1990. Data on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Boise, ID. Clayton, J. L.; Kellogg, G.; Forrester, N. 1987. Soil disturbance-tree growth relations in central Idaho clearcuts. Res. Note INT-372. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station. 6 p. Connaughton, C. A. 1935. Forest fires and accelerated erosion. Journal of Forestry. 33: 751-752. DeBano, L. F.; Mann, L. D.; Hamilton, D. A. 1970. Translocation of hydrophobic substances into soil by burning organic litter. Soil Science Society of America Proceedings. 34: 130-133. Froehlich, H. A. 1988. Causes and effects of soil degradation due to timber harvesting. In: Lousier, J. D.; Still J. W., eds. Degradation of forest land: "Forest soils at risk": Proceedings, 10th British Columbia soil science workshop; 1986 February; Land Manage. Rep. 56. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Forests: 3-12. Howes, S. W. 1988. Consideration of soil productivity during forest management activities: the USDA Forest Service approach in the Pacific Northwest. In: Lousier, J. D.; Still, J. W., eds. Degradation of forest land: "Forest soils at risk": Proceedings, 10th British Columbia soil science workshop; 1986 February; Land Manage. Rep. 56. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Forests: 185-190. Jensen, F.; Cole, G. 1965. South Fork Salmon River storm and flood report. Unpublished report on file at: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Payette National Forest, McCall, ID. Kimmins, J. P.; Scoullar, K. A.; Chatarpaul, L. 1988. Long term impacts of forest management on soil fertility and forest productivity: a systems analysis approach using FORCYTE. In: Lousier, J. D.; Still, J. W., eds. Degradation of forest land: "Forest soils at risk": Proceedings of the 10th British Columbia soil science workshop; 1986 February; Land Manage. Rep. 56. Victoria, BC: British Columbia Ministry of Forests: 116-129. Klock, G. O. 1982. Some soil erosion effects on forest soil productivity. In: Determinants of soil loss tolerance. 150