SOILS INFORMATION: A VALUABLE TOOL FOR MANAGEMENT OF WESTERN-MONTANE FORESTS

This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain.

SOILS INFORMATION: A VALUABLE

TOOL FOR MANAGEMENT OF

WESTERN-MONTANE FORESTS

Richard F. Fisher

ABSTRACT

Soils information mapped and interpreted at large scales can be very useful in forest management. Such information is objective rather than subjective. It can be aggregated for use at smaller scales and can be placed free of scale errors into geographic information systems. It can be interpreted for a wide variety of uses. Unfortunately, our ability to collect and interpret such information for western-montane forests in a timely manner is severely limited by a lack of trained personnel and appropriate basic studies.

INTRODUCTION

To say that vegetation is not related to the soil on which it grows is akin to saying that vegetation is not related to the local climate. Yet we not only hear this statement said, but we also see it written. If we compare 1:500,000 maps of Koppen's climatic regions with similar scale maps ofbiomes they compare favorably, but if we were to compare the efficacy of Koppen's system for predicting vegetation types at a scale ofl:12,000, we would be forced to conclude that vegetation and climate are not related.

Similarly, Marbut's soil great groups match biomes fairly well in eastern North America. They fail miserably in the

West due to the rapid changes in both soils and vegetation with changes in altitude. Certainly if we investigate the efficacy of Marbut's soil units for predicting vegetation type at a scale of 1:12,000, we must conclude that vegetation and soils are not related.

Of course we know that vegetation is related to microclimate, and if we measure and map microclimate we can predict vegetation types fairly well even at a scale of

1:12,000. Soil should have similar efficacy, microsoil that is. Unfortunately, we have not looked much at soil in this detail in the West. In the Southeast, where very small changes in elevation «5 ft) lead to large changes in both soil properties and tree growth, we have looked at soils in great detail. This investigation has revealed that not only vegetation type but even growth is closely related to soil type (Fisher 1984).

In the Mountain West, due to the cooler or drier environment and the youthful landscape, large changes in elevation (>100 ft) may yield only minor changes in vegetation and soil. This has certainly helped to foster the idea that soil does not drive vegetation in the West, but there are many other factors that contribute to soils' poor image.

Paper presented at the Symposium on Management and Productivity of Western-Montane Forest Soils, Boise, ID, April 10-12, 1990.

Richard F. Fisher is Professor and Head, Department of Forest Resources, Utah State University, Logan, UT 84322-5215.

INFORMATION DEMAND

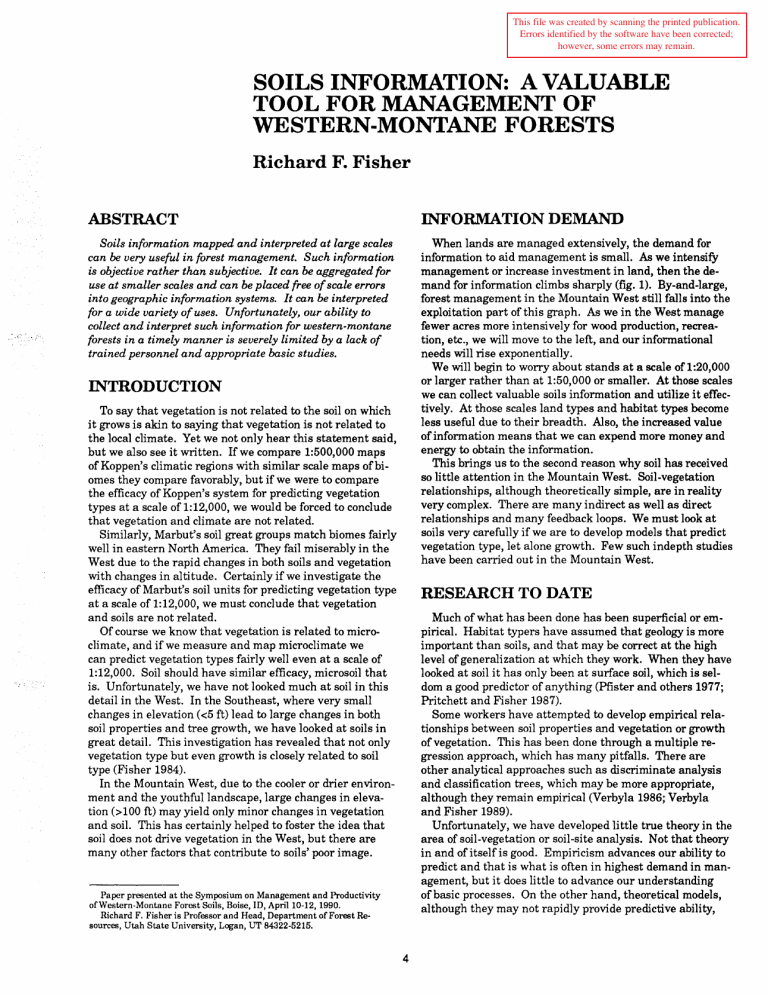

When lands are managed extensively, the demand for information to aid management is small. As we intensifY management or increase investment in land, then the demand for information climbs sharply (fig. 1). By-and-Iarge, forest management in the Mountain West still falls into the exploitation part of this graph. As we in the West manage fewer acres more intensively for wood production, recreation, etc., we will move to the left, and our informational needs will rise exponentially.

We will begin to worry about stands at a scale of 1:20,000 or larger rather than at 1:50,000 or smaller. At those scales we can collect valuable soils information and utilize it effectively. At those scales land types and habitat types become less useful due to their breadth. Also, the increased value of information means that we can expend more money and energy to obtain the information.

This brings us to the second reason why soil has received so little attention in the Mountain West. Soil-vegetation relationships, although theoretically simple, are in reality very complex. There are many indirect as well as direct relationships and many feedback loops. We must look at soils very carefully if we are to develop models that predict vegetation type, let alone growth. Few such indepth studies have been carried out in the Mountain West.

RESEARCH TO DATE

Much of what has been done has been superficial or empirical. Habitat typers have assumed that geology is more important than soils, and that may be correct at the high level of generalization at which they work. When they have looked at soil it has only been at surface soil, which is seldom a good predictor of anything (Pfister and others 1977;

Pritchett and Fisher 1987).

Some workers have attempted to develop empirical relationships between soil properties and vegetation or growth of vegetation. This has been done through a multiple regression approach, which has many pitfalls. There are other analytical approaches such as discriminate analysis and classification trees, which may be more appropriate, although they remain empirical (Verbyla 1986; Verbyla and Fisher 1989).

Unfortunately, we have developed little true theory in the area of soil-vegetation or soil-site analysis. Not that theory in and of itself is good. Empiricism advances our ability to predict and that is what is often in highest demand in management, but it does little to advance our understanding of basic processes. On the other hand, theoretical models, although they may not rapidly provide predictive ability,

4

Input

Low

: : :: EXPLOITED :::::

~:

: : "';';'" ".;.;," ".;.;," ".;.;," ",.;.;" ",.;.;" ",.;.;" ".;,;"

"~"

PROTECTED REMOTE

WILDLANDS

J. _______ .

Figure 1-Schematic spectrum of the levels of forest management and degree of cultural control of the forest. (Adapted from Stone

1975")

DOMESTICATED

FOREST

• _____ rapidly advance our understanding. When empirical models fail to meet our expectations we adjust the coefficients in order to improve the fit. When theoretical models fall short we must question our basic assumptions, our theory.

Although the theoretical basis of habitat types is little more advanced than our own, the development of theorybased ecological models has done much to advance our basic understanding of ecological processes. Clearly there is a place for the future development of soil-vegetation, soil-site theory, and the development of models to test that theory. We likely cannot attain a complete understanding of these complex process level interactions in the absence of such theory.

WHERE FROM HERE?

In general our efforts to develop a good understanding of how soils influence vegetation distribution and growth in the Mountain West have been fragmented and feeble.

However, they may have been appropriate in light of the intensity of forest management. Where do we go from here? Is there a demand for better soils information?

Do we have the tools necessary to meet that demand in a timely manner?

My guess is that more site-specific management planning will be required on both public and private forest land in the Mountain West. I know that good soils information can be very valuable in such efforts. Soils information has several advantages over habitat type, land type, or similar information in such planning applications.

In the first place it is objective rather than subjective. It is subject to less personal bias on the part of the classifier/ mapper, and it is independent of current use standards and product strictures. It can be reinterpreted endlessly using new suitability and feasibility constraints.

Second, it is best collected at a large scale, but it can be aggregated easily for use at smaller scales. This is important when some decisions will be regional in nature, while others will be stand or location specific. It is also essential for error-free incorporation into geographic information systems.

Third, it can be interpreted for a wide variety of uses.

When soil units have been adequately defined and interpretations properly and thoroughly developed, soils information is equally valuable to the silviculturist, recreation manager, hydrologist, range conservationist, wildlife manager, fisheries biologist, and even archeologist. This universality is unmatched by any other kind oflandscape information, save legal property descriptions.

5

This all means to me that there should and will be an increasing demand for good soils information. The question then is can we supply it in a timely manner? My suspicion is that the answer is no. We have neither the cadre of trained personal to collect it nor the basic understanding of what it is we should seek to supply.

What are the most important features of the soils of the

Mountain West? Organic matter in the A horizon, texture of the B horizon, percent coarse fragments and depth to bed rock, drainage class, acidity, mineralizable nitrogen? How should we develop soil taxa, and how should these taxa be delineated on the landscape (mapped)? Should we emulate the Soil Conservation Service, Weyerhaeuser, International

Paper, or the procedures used by Forest Service elsewhere in the Country? And who and how will we train the army of people necessary to collect, interpret, and catalog this mountain of information?

I know I don't have the answers to these questions, and

I doubt that anyone here has them. Hopefully, one of the things that will come out of this meeting is a mechanism for addressing these questions. We have shown in the

East, South, and Midwest that we can classify and map soils and develop soil interpretations that prove to be extremely valuable in natural resource management. Surely we can do the same in the West, but it won't be easy.

REFERENCES

Fisher, R. F. 1984. Predicting tree and stand response to cultural practices. In: Stone, E. L., ed. Forest soils and treatment impacts; 1983 June; Knoxville, TN. Knoxville,

TN: University of Tennessee: 53-65.

Pfister, R. D.; Kovalchik, B. L.; Arno, S. F.; Presby, R. C.

1977. Forest habitat types of Montana. Gen. Tech. Rep.

INT-34. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station. 174 p.

Pritchett, W. L.; Fisher, R. F. 1987. Properties and management of forest soils. New York: John Wiley and Sons.

494p.

Stone, E. L. 1975. Soil and man's use of forest land. In:

Bernier, B.; Winget, C. H., eds. Forest soils and forest land management. Quebec, PQ: University of Lavel

Press: 1-9.

Verbyla, D. L. 1986. Potential prediction bias in regression and discriminant analysis. Canadian Journal of Forest

Research. 16: 1255-1257.

Verbyla, D. L.; Fisher, R. F. 1989. An alternative approach to conventional soil-site regression modeling. Canadian

Journal of Forest Research. 19: 179-184.