FORAGE KOCHIA COMPETITION WITH CHEATGRASS IN CENTRAL UTAH E. Durant McArthur

FORAGE KOCHIA COMPETITION

WITH CHEATGRASS IN CENTRAL

UTAH

E. Durant McArthur

A. Clyde Blauer

Richard Stevens

ABSTRACT

Forage kochia (Kochia prostrata [L.] Schrad.) plantings on cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum £.)-dominated highway rights-of-way and near an abandoned farm also dominated by cheatgrass showed forage kochia to be competitive with cheatgrass. The forage kochia plantings were made between 1970 and 1979 at about a dozen mostly semiarid study sites in three central Utah counties

(Carbon, Sanpete, Sevier) and evaluated between 1986 and 1988. Recruitment of new forage kochia plants at most study sites demonstrates that the species is becoming integrated into the existing plant communities. Some plants have established in nearby, more natural communities. A wildfire at one site provided evidence that forage kochia is adapted to recovery after.burning, an important characteristic for any species that is to coexist with large, dominant cheatgrass populations.

INTRODUCTION

Forage kochia (Kochia prostrata [L.] Schrad.) is a long-lived, woody-based shrub or subshrub, ranging in height from less than 30 to over 100 em (12 to 40 inches)

(fig. 1). It is native to arid and semiarid regions of central

Eurasia, extending to the Mediterranean Basin and northeastern China (fig. 2), where it grows on alkaline, stony, and sandy steppes and plains at elevations ranging from 0 to 2,400 m (0 to 8,000 ft) (Balyan 1972). The species includes considerable taxonomic diversity. Balyan

(1972) recognized a green subspecies (ssp. virescens) and a grey one (ssp. grisea) with additional varieties in the latter subspecies. Although each taxon encompasses considerable adaptive variation, each is best adapted to a particular soil type and climatic regime (Balyan 1972;

Shishkin 1936). The species forms a polyploid complex based on x

=

9 (Herbel and others 1981; McArthur and

Sanderson 1989; Pope and McArthur 1977).

Figure 1-Line drawing (about one-fifth actual size)

·of 'Immigrant' forage kochia (Kochia prostrata ssp. virescens).

Paper presented at the Symposium on Cheatgrass Invasion, Shrub Die-

Off, and Other Aspects of Shrub Biology and Management, Las Vegas, NV,

April 5-7, 1989.

E. Durant McArthur is Project Leader and Chief Research Geneticist,

Intermountain Research Station, Forest Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Shrub Sciences Laboratory, Provo, UT 84606. A. Clyde Blauer is

Professor, Division ofNatural Sciences, Snow College, Ephraim, UT 84627 and seasonal Botanist, Intermountain Research Station. Richard Stevens is Project Leader and Wildlife Biologist, Wildlife Habitat Restoration

Project, Utah Division of Wildlife Resources, Ephraim, UT 84627.

Forage kochia is well adapted to the climate and soils of the Intermoutain area, especially in the pinyon-juniper, sagebrush, and salt desert shrub communities (Keller and Bleak 1974; McArthur and others 1974; Stevens and others 1985). It is a valued plant for animal forage and for rehabilitation of disturbed soils both in Eurasia

(Alimov and Amirkhanov 1980; Balyan 1972; Nechaeva

1985; Nechaeva and others 1977; Nemati 1977) and westem North America (Aldan and Pase 1981; Davis 1979;

56 This file was created by scanning the printed publication.

Errors identified by the software have been corrected; however, some errors may remain.

:ao

20

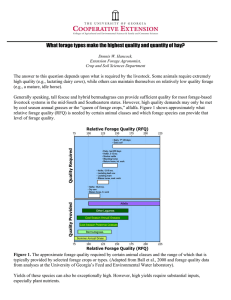

Figure 2-Natural distribution of Kochia prostrata. Adapted from Shishkin (1936). The solid line outlines the area of distribution. The Roman numerals refer to floristic provinces: Ill, Central European; V', Western Mediterranean;

v·,

Eastern Mediterranean; VI, Balkan Peninsula and Asia Minor; VII, Lesser Armenia

. and Kurdistan; VIII, Iran; IX, India and Himalayas; X, Sinkiang; XI, Mongolia; XII, China and Japan; XV,

Tibet.

Davis and Welch 1984, 1985; McArthur and Stevens 1983;

McArthur and others 1974; Otsyina 1983; Stevens and others 1985).

Like forage kochia, cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum L.) is a native to Eurasia that is also well adapted to the

Intermountain area (Mack 1981). Unlike forage kochia, however, cheatgrass is an unwanted invader because it has displaced productive native vegetation by its competitive establishment and fire climax characteristics

(Leopold 1949; Pickford 1932; Piemeisel1951; Young and others 1979).

This set of studies was undertaken to document the competitive interactions between forage kochia and cheatgrass and other annual weeds in central Utah areas where these annuals are naturalized and forage kochia had been seeded.

MATERIALS, METHODS, AND STUDY

SITES

Three studies were undertaken. Taxonomic nomenclature follows Welsh and others (1987), except names for grasses followed the traditional treatment of Hitchcock

(Hitchcock and Chase 1971; Plummer and others 1978).

For taxonomic treatment of big sagebrush (Artemisia tri-

dentata) and rubber rabbi thrush ( Chrysothamnus nau-

seosus) subspecies see McArthur (1983) and McArthur and Meyer (1987), respectively. Origin of plant species

(native or introduced) was taken from Welsh and others

(1988) and Albee and others (1988). The ecological measures density and cover class (Cox 1967; Daubenmire 1969) were used to measure performance of forage kochia and associated plants. Our density values are given as plantslm 2 (10.8 ft 2). Our cover class values were modified slightly from those suggested by Daubenmire to cover classes 1, <1 percent; 2, 1-5 percent; 3, >5-25 percent;

4, >25-50 percent; 5, >50-75 percent; 6, >75-95 percent;

7, >95-100 percent.

Study One: Roadside Plantings

In the first study, experimental plantings in disturbed highway rights-of-way in Sanpete and Sevier Counties were established (table 1). The study reported here includes data collected during the summers of 1986-1988 from forage kochia seedings between 1972 and 1979. Study sites were surface seeded with 'Immigrant' forage kochia; seeds were raked lightly into the seedbed. 'Immigrant' is

57

Table 1-Locations and descriptions of study sites for the roadside planting study

Location and elevation Description

Transect number Site

Ephraim Canyon,

Sanpete Co.

Roadside, burned, and unburned

2

Nine Mile Reservoir,

Sanpete Co.

North of Sterling,

Sanpete Co.

Redmond Cut,

Sevier Co.

Redmond Junction,

Sanpete Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Salina Canyon,

Sevier Co.

Along 1-70, Milepost 57.8, north side. 1, 730 m

(5,670 ft)

Along 1-70, Milepost58,north side. 1, 725 m

(5,660 ft)

Along 1-70, Milepost 58.5, south side. 1, 735 m

(5,690 ft)

Along 1-70, Milepost 60, north side. 1, 750 m

(5,740 ft)

Along 1-70, Milepost 7 4, south side. 2,200 m

(7,220 ft)

Along 1-70, Milepost 76, south side. 2,230 m

(7,320 ft)

Mouth of Canyon, along Ephraim-

Orangeville Road.

1,780 m (5,840 ft)

Along U.S. Highway 89. 1,645 m

(5,400 ft)

Along U.S. Highway 89. 1,675 m

(5,500 ft)

Along U.S. Highway 89. 1,570 m

(5,150 ft)

Along U.S. Highway 89. 1,575 m

(5,160 ft)

Along 1-70, Mouth of Canyon. 1,615 m

(5,300 ft)

Cut, natural

Cut, natural, pasture

Cut, crest

Roadside

Cut, natural

Cut

Cut, natural

(Kochia prostrata and Ceratoides lanata plantings)

Cut, natural

(Kochia prostrata and Ceratoides

Janata plantings)

Cut

Cut

Cut

2

3

3

2

2

3

2

4

2

Quadrat number

10

35

20

25

10

10

10

15

10

15

25

20

58

a selection from P.I.line 314929 of K prostrata ssp. vires- cens (Stevens and others 1985). The total study, including the performance of many more plant species, will be reported elsewhere (Blauer and others 1989).

Density and cover class data were collected from 205m 2

(3.28-ft 2

) quadrats on 27 linear transects from 12 study sites (table 1). Transects were up to 50 m (168ft) long with quadrats located at regular intervals on alternate sides of the transect at 3- to 8-m (9.8- to 26.2-ft) intervals.

The intervals were regularly spaced in each transect with the interval value being determined by the length of the transect, which in tum was determined by the boundaries of homogenous sampled sites. The transects ran through the highway rights-of-way (mostly roadcuts) out into relatively undisturbed rangelands and pastures in random compass directions not intersecting the highways.

These were mostly semiarid sites (average annual precipi tion range from less than 25 to more than 60 em

(10 to 25 inches), of varied slope (range= 0 to 61 percent), over an elevational range of 1,575 to 2,165 m (5,170 to

7,100 ft). The general soil types vary from aridisols through entisols to mollisols (Johnson 1989; Stevens and others 1983).

Study Two: Wildfire

This study was a small one drawn from the larger

Study One. It differed from other aspects of the first study in that a wildfire had burned through part of this forage kochia seeding. This site was seeded in 1979.

The wildfire occurred in 1983 or 1984.

Transects were placed in the adjacent burned and unburned areas. The quadrats on the burned site were spaced at 5-m (16.4-ft) intervals; the quadrats on the unburned site were at 6-m (19.7-ft) intervals (table 1).

This study site was near the mouth of Ephraim Canyon.

The soil type is Sanpete stony fine sandy loam with a slope of about 5 percent, an aspect of 315°, and mean annual precipitation of29.7 em (11.7 inches) (Price and

Evans 1937; Swenson and others 1981).

Study Three: Cheatgrass Invasion of an Abandoned Farm

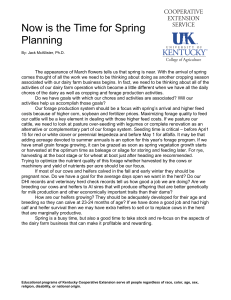

The spread of forage kochia into an abandoned farm at the Gordon Creek Wildlife Management Area was examined in this study (fig. 3). A small ( <0.25-ha; 0.45-acre)

Scofield Spring Glenn

Consumer Road

Gordon Creek

Wildlife Management

Area

Boundary of Abandoned Farm

Y

Area Seeded to Forage Kochia, 1970 t---1

30m figure 3-Map of abandoned dry farm area at Gordon Creek, Carbon

County, UT. t

N

59

plot in a pinyon-juniper (Pinus edulis-Juniperus osteo-

spermus) chaining near the abandoned farm was seeded to forage kochia during the fall of 1970. The seed was broadcast between double chainings (Plummer and others

1968). The forage kochia for the seeding was K. prostrata ssp. grisea (P.I. 356821).

Two transects in random directions were established and read from the seeded area through the abandoned farm in September 1988 (fig. 3). Species composition, density, and cover class data were collected from 4-m 2

(13.1-ft 2

) quadrats placed on alternating sides of the transects every 15m (49.2 ft). This site is at 2,130 m

(6,985 ft) elevation, receives about 29 em (11.4 inches) of annual precipitation, and is an aridisol soil type

(Hutchings and Murphy 1989; McArthur and Welch

1982).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Study One: Roadside Plantings

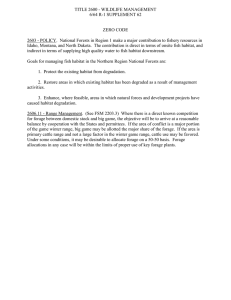

'Immigrant' forage kochia performed well in the highway right-of-way plantings (fig. 4; table 2). As table 2 demonstrates, forage kochia grows well in association with native and introduced, annual and perennial, and herbaceous and woody species. In addition to introduced annual cheatgrass, three introduced perennial grasses

(Agropyron cristatum, A. intermedium, Dactylis glomer-

ata), four native perennial grasses (Agropyron smithii,

A. spicatum, Oryzopsis hymenoides, Sitanion hystrix), six introduced annual forbs (Erodium cicutarium, Malcolmia africana, Melilotus officinalis, Ranunculus testiculatus,

Salsola iberica, Tragopogon dubius), the native annual forb Lactuca serriola, two perennial native forbs (Erio-

gonum umbellatum, Grindelia squarrosa), and seven native shrubs (Artemisia tridentata, Atriplex canescens,

A confertifolia, Ceratoides lanata, Chrysothamnus

nauseosus, C. viscidiflorus, Gutierrezia sarothrae) were commonly associated with forage kochia on the transect quadrats (table 2).

. Other species that less commonly occurred with forage kochia in the quadrats were the annual introduced grasses Aegilops cylindrica and Secale cereale; the introduced perennial grasses Agropyron elongatum, A repens,

Bromus inermis, Festuca ovina, and Poa bulbosa; the native perennial grasses Elymus cinerus, Hilaria jamesii,

Poa nevadensis, P. secuttda, Sporobolus contractus, and

Stipa comata; the introduced annual forbs Descurainia

sophia, Halogeton glomeratus, Kochia scoparia, and

Lepidium perfoliatum; the native annual forbs Crypthan-

tha spp., Eriogonum hookerii, Gilia spp., Lappula occi-

dentalis, Microsteris gracilis, and Oenothera spp.; the introduced perennial forbs Convolvulus arvensis, Medi-

cago sativa, Onobrychis viciaefolia, and Sanguisorba mi-

nor; the perennial native forbs Arenaria spp., Astragalus spp., Astragalus kentrophyta, Calochortus nuttallii, Erio- gonum brevicaule, Gilia congesta, Hedysarum boreale, Iva

axillaris, Phlox hoodii, P. longifolia, Physaria spp., Sphae-

ralcea coccinea, and S. grossulariaefolia; and the native shrubs Artemisia nova, A. pygmaea, Ephedra nevadensis,

E. viridis, Kochia americana, Opuntia spp., Tetradymia

canescens, T. spinosa, and Sarcobatus vermiculatus.

Forage kochia's performance as evidenced by it highest mean cover class value of all species (table 2), high rank among the species in density (it is exceeded only by the annuals cheatgrass, storksbill [Erodium cicutarium] bur buttercup [Ranunculus testiculatus ], and Russian thistle [Salsola iberica]), success in areas where it was planted (it is present on all 22 sites and in 24 of the 27 transects), and its ability to grow and persist on the disturbed roadsides as well as on more natural and pasture sites (table 1), show it to be well adapted to our study sites. It competes well with cheatgrass, other disturbanceadapted species, and, indeed, with all species at our study sites.

Forage kochia is sustaining its position in the plant communities studied as is demonstrated by the presence of seedlings as well as mature plants on the study sites.

Seedlings in the quadrats were observed for only three species during the data collection period, black sagebrush

(Artemisia nova), Russian thistle, and forage kochia. Of these, only forage kochia had seedlings at more than one site. Moreover, forage kochia had seedlings at all12 sites and in 75 percent of the transects that included mature forage kochia plants. Forage kochia seedlings averaged a cover class value of 1.5 ± 0.6 (range, 1-3) and a density of

18.2 ± 21.5 (range, 0.2-72.8). These numbers suggest that forage kochia will be an integral part of plant communities at the study sites for the foreseeable future. Forage kochia plants have become established up to 100 m (328ft) distant from original seeding sites into natural and pasture plant communities as well as the severely disturbed highway right-of-way sites. Figure 4 shows examples of forage kochia occupancy of highway right-of-way plantings.

60

A

8

Figure 4-Photographs of seeded 'Immigrant' forage kochia in Salina

Canyon, UT. (A) Site near mouth of canyon along Interstate Highway

·15 (1-15). Dark plants (foreground) are forage kochia plants. Note the exclusion of cheatgrass by forage kochia (foreground) as compared to abundant cheatgrass behind fence (arrow) where forage kochia was not seeded but is invading. (B) Site near milepost 58 along 1-15 in

Salina Canyon, UT. Dark shrubs in foreground are forage kochia plants. Lighter shrubs in background (arrow) are winterfat plants.

61

Table 2-Species density and cover class values from disturbed roadside plantings in central Utah

Specles

1

(Life form, name) Orlgln

2

Number of sites

Number of transects

Cover class

Range Mean±sd Range

Dens it~

Mean±sd

Annual grass

Bromus tectorum

Perennial grasses

Agropyron cristaturrt

Agropyron intermediurr/t· 5

Agropyron smithir

Agropyron spicatum

Dactyl is glomerata

Oryzopsis hymenoidesS

Sitanion hystrixS

N

N

N

N

11

9

5

3

4

4

8

6

18

11

7

3

5

4

12

7

1-4

1-3

1-4

1-3

1-2

1-2

1-3

1-2

1.8 ±0.9

2.3±0.8

2.5 ± 1.0

1.7± 1.2

1.2 ± 0.4

1.2 ±0.5

1.8±0.2

1.6±0.5

0.1-265.0

0.1-8.2

0.2-29.0

0.3-65.7

0.1-1.1 tr-6-0.5 tr-1.7

0.1-2.3

57.4±87.0

3.3 ± 3.1

9.3 ± 11.0

22.8 ± 37.2

0.4±0.4

0.3 ±0.2

0.4 ±0.5

0.9 ±0.7

Annual forbs

Erodium cicutarium

Lactuca serriola 7

Malcolmia african a

Me/ilotus officinalis 7

Ranuncu/us testicu/atus

Sa/sola iberica

Tragopogon dubius

Perennial forbs

Eriogonum umbel/a tum

Grindelia squarrosa

N

N

N

3

4

3

5

9

5

3

3

4

3

6

4

5

14

7

4

6

4

1-3

1-2

1-2

1-3

1-2

1-2

1-2

1-2

1.7± 1.2

1.2 ±0.5

1.0±0

1.2±0.4

1.6 ±0.6

1.3±0.5

1.2 ±0.5

1.5 ±0.5

1.2 ±0.5

0.2-55.5

0.1-5.2

0.1-2.2 tr-0.1

0.3-132.2

0.1-31.9 tr-1.0

0.1-4.0

0.1-0.3

20.2 ±30.6

1.9 ± 5.4

0.9±0.9

0.1 ± tr

40.4±52.5

7.9 ± 10.9

0.5±0.4

1.3 ± 1.5

0.2 ± 0.1

Shrubs

Artemisia tridentataB

A triplex canescens

A triplex confertifolia

Ceratoides

Ia nata

Chrysothamnus nauseosusB

Chrysothamnus

Viscidiflorus

Gutierrezia sarothrae

Kochia prostrata

N

N

N

N

N

N

N

I

3

3

5

3

7

5

3

3

7

3

7

7

1-3

1-2

1-3

1-3

1-2

1-3

1.7± 1.2

1.3 ±0.6

2.3 ± 1.0

2.3 ± 1.2

1.7±0.5

1.4±0.8

0.1-0.6 tr-tr

0.1-1.2

0.4-1.2 tr-1.0

0.2-2.0

0.3 ±0.3 tr ± tr

0.4 ±0.4

0.9 ±0.4

0.3±0.3

0.6 ±0.6

3

12

3

19

1-3

1-4

1.7± 1.2

2.9 ±0.9

0.3-1.1 tr-21.4

0.7±0.4

7.4 ±6.5

1

0nly those species that occurred on a minimum of three sites were included. See text for other associated species.

2 1 =introduced, N =native. Determined from Welsh and others (1987) and Albee and others (1988).

3 1ncludes Agropyron desertorum.

'*Includes Agropyron trichophorum.

5New generic names are given in Barkworth and Dewey (1985) and Arnow (1987).

6fr =trace.

1"fhese species may also be biennials.

'These species include subspecies. For Artemisia tridentata these were ssp. tridentata and wyomingensis and for Chrysothamnus nauseosus these were ssp.

consimilis, graveolens, and hololeucus.

62

Study

Two:

Wildfire

We examined the response offorage kochia to a wildfire. Since cheatgrass is a fire climax species (Mack

1981), the response of forage kochia to fire is an important characteristic to consider in its competitive relationship to cheatgrass. The data we collected from the site showed that under the unknown (intensity, season) circumstances of that fire, forage kochia survived and is maintaining a vigorous population (table 3). There was apparent mortality of some mature plants, but many survived and recruitment has been successful.

This study is a small one covering only a limited area

(approximately 800 m 2

;

9,600 ft 2

).

Originally, before being seeded, the area was dominated by Wyoming big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata ssp. wyomingensis), threadleaf rubber rabbi thrush ( Chrysothamnus nauseosus ssp. consimilis), hairy low rabbitbrush (C. viscidifiorus ssp. puberulus), Utah juniper (Juniperus osteosperma), and gray horsebrush (Tetradymia canescens). Based on our limited data base, it appears as if forage kochia, crested wheatgrass (Agropyron cristatum), and bulbous bluegrass (Poa bulbosa) were not materially affected by the fire. Jointed goat grass (Aegilops cylindrica),

Wyoming big sagebrush, threadleafrubber and hairy low rabbitbrushes, sheep fescue (Festuca ovina), Utah juniper, Indian ricegrass (Oryzopsis hymenoides), and gray horsebrush have decreased in importance or were wiped out by the fire. Cheatgrass, field bindweed (Convolvulus arvensis), storksbill, curly cup gum weed (Grindelia squarrosa), broom snakeweed (Gutierrezia sarothrae) sainfoin (Onobrychis viciaefolia), bur buttercup, bottle ' brush squirrel tail (Sitanion hystrix), and scarlet globemallow (Sphaeralcea coccinea) populations were enhanced by the fire.

Fire tolerance of forage kochia has not, to our knowledge, been documented before in the literature. This important characteristic needs more study. If fire tolerance is strong and consistent, the species' contribution to stability and productivity on cheatgrass-dominated lands will be enhanced. Monsen and Kitchen (1989) have data on the recovery of forage kochia following a burn subsequent to the one we report. Their data are from a planting of 'Immigrant' in southeastern Idaho. Monsen and

Kitchen and colleagues are also investigating response

Table 3-Density and cover class comparisons of forage kochia at burn site

Parameter

Burned site Unburned site

(N

=

5) (N

=

5)

Average density

Mature plants

Seedlings

Average percent cover

Mature plants

Seedlings

3.4±1.7

4.6 ± 4.1

4.2 ± 2.8

0.2 ± 0.1

12.8 ± 5.2

2.8 ± 1.4

19.2±11.2

0.4 ±0.1 of several forage kochia accessions to quantitative (intensity, fuel load, season) fire events. The fire event we documented showed that 'Immigrant' forage kochia can recover from at least some fires 4 or 5 years after seeding.

Study Three: Cheatgrass Invasion of an Abandoned Farm

In this study forage kochia moved from a small initial

1970 seeding through an abandoned cheatgrass-infested farm. (fig. 3). By the time we collected data (1988), forage kochia had spread throughout the field. It had moved the entire length of both transect lines, each over 400 m

(1,312 ft) long, into the fringe of the native Wyoming big sagebrush-pinyon-juniper community to the south and east.

Forage kochia had not moved more than 15m (49.2 ft) into the native woodland. In the abandoned farm however, it was an integral part of the existing

veget~tion

(table 4). As a matter of record (based on 61 2- by 2-m

[~.6by 6.6-ft] quadrats), forage kochia had average densities of 0.6 for mature (fruiting) plants, 2.6 for immature

(>1-year old but not fruiting) plants, and 6.4 for seedlings for a total of9.6 plants per m

2 in the old farm. Forage kochia was the single most dominant perennial cover

(35.2 percent). Its cover was approximately equal to the perennial grass cover contributed by 10 species (table 4).

Its distribution throughout the old dry farm is underscored by its presence in 46 of the 61 studied quadrats

(75 percent). In this study as in Study One, forage kochia achieved its place in the plant community despite a formidable cheatgrass presence.

Table 4-Percent cover by species or class on a cheatgrassdominated, abandoned dry farm, Gordon Creek Wildlife

Management Area

Plant Mean±sd Range Quadrat presence

1

Cheatgrass

Forage kochia

Perennial grasses

2

Annuals, excluding cheatgrass

3

Field bindweed 4

Perennial forbs

5

Shrubs

6

Trees

7

41.4 ± 27.2

6.8 ± 12.1

7.3 ± 10.8

3.2±6.8

1.7± 2.5

1.4 ± 3.0

1.6 ± 6.5

0.5±3.8

0-85

0-60

0-40

0-35

0-10

0-15

0-47

8

0-30

59

46

40

38

38

21

7

1

1 0ut of 61 quadrats.

2 1ncludes Agropyron aistatum, A. smithii, Bromus inermis Boutefoua eriopoda, Elymus junceus, E. safinus, Oryzopis hymenoides, Poa secunda

Sporobofus airoides, and Sitanion hystrix. '

3 !ncludes Amaranthus a/bus, Sa/sofa iberica, and a few unidentified

SpecieS.

"'Convolvulus arvensis.

5 Medicago sativa and Sphaeralcea grossulariaefolia.

6 Artemisia nova, .A. tridentata ssp. wyomingensis, Chrysothamnus

nauseosus, and Gutteffezia sarothrae.

7

Juniperus osteosperma.

SOverstory presence only.

63

A CONCLUDING WORD

Forage kochia, a valuable perennial forage and groundcover shrub, competes well with cheatgrass under many circumstances. This was made evident in our studies, which included several sites of contrasting vegetative communities, topography, soil types, precipitation, time periods, and a wildfire. Two forage kochia subspecies performed well.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

These studies were faciliated by Federal funds from the Pittman-Robertson W-82-R Project for wildlife habitat restoration; cooperators were: Utah Division of Wildlife

Resources and Intermountain Research Station, and by Cooperative Agreement No. 22-C-5-INT-004 between the Intermountain Research Station and Snow College.

A. Perry Plummer initiated the ground work for these studies; we gratefully acknowledge his guidance and stimulation. Gary L. Jorgensen, Kent R. Jorgensen, and the Sanpete County Older American Green Thumb crew helped establish the experimental plantings.

REFERENCES

Albee, B. J.; Shultz, L. M.; Goodrich, S. 1988. Atlas of the vascular plants of Utah. Salt Lake City, UT: Utah

Museum of Natural History. 670 p.

Aldon, E. F.; Pase, C. P. 1981. Plant species adaptability on mine spoils in the southwest: a case study. Res. Note

RM-398. Fort Collins, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Forest and Range

Experiment Station. 3 p.

Alimov, E.; Amirkhanov, Zh. 1980. Breeding of Kochia prostrata Schard. in deserts of southeastern

Kazakhstan. Problems of Desert Development.

3: 57-60.

Arnow, L.A. 1987. Gramineae A. L. Juss. In: Welsh, S. L.;

Atwood, N.D.; Goodrich, S.; Higgins, L. C., eds. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs. 9: 684-788.

Balyan, G. A. 1972. Prostrate summer cypress and its culture in Kirghizia. Frunze, USSR: lsdatel'stovo

"Kyrgyzstan." (Translated from Russian; U.S. Department of Commerce, TT77 -59026, 1979). 296 p.

Barkworth, M. E.; Dewey, D. R. 1985. Genomically based genera in the perennial Triticae of North America.

American Journal of Botany. 72: 767-776.

Blauer, A. C.; McArthur, E. D.; Stevens, R. 1989. Evaluation of roadside plantings in central Utah. Data on file at: ·U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service,

Intermountain Research Station, Shrub Sciences Laboratory, Provo, UT; RWU 4251 files.

Cox, G. W. 1967. Laboratory manual of general ecology.

Dubuque, lA: Wm. C. Brown Company. 165 p.

Daubenmire, R. 1969. A canopy-coverage method of vegetational analysis. Northwest Science. 33: 43-64.

Davis, A. M. 1979. Forage quality of prostrate kochia compared with three browse species. Agronomy

Journal. 71: 822-824.

Davis, J. N.; Welch, B. L. 1984. Seasonal variation in crude protein content of Kochia prostrata. In:

Tiedemann, A. R.; McArthur, E. D.; Stutz, H. C.;

Stevens, R.; Johnson, K. L., compilers. Proceedingssymposium on the biology of Atriplex and related chenopods; 1983 May 2-6; Provo, UT. Gen. Tech. Rep.

INT-172. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture,

Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range Experiment Station: 145-149.

Davis, J. N.; Welch, B. L. 1985. Winter preference, nutritive value, and other range characteristics of Kochia prostrata (L.) Schrad. Great Basin Naturalist. 45:

778-783.

Herbel, C. H.; Barnes, R. F.; Heady, H. F.; Purdy, L. N.

1981. Range research in the Soviet Union. Rangelands.

3: 61-63.

Hitchcock, A. S.; Chase, A. 1971. Manual of the grasses of the United States. New York: Dover Publications.

1051 p. (in two volumes).

Hutchings, T. B.; Murphy, D. R. 1989. Soils. In: Johnson,

K. L., ed. Rangeland resources of Utah. Logan, UT:

Utah State University, Cooperative Extension Service:

15-17.

Johnson, K. L., ed. 1989. Rangeland resources of Utah.

Logan, UT: Utah State University, Cooperative Extension Service. 103 p.

Keller, W.; Bleak, A. T. 1974. Kochia prostrata: a shrub for western ranges? Utah Science. 35: 24-25.

Leopold, A. 1949. A sand county almanac. New York:

Oxford University Press. 269 p.

Mack, R.N. 1981. The invasion of Bromus tectorum L. into western North America: an ecological chronicle.

Agro-Ecosystems. 7: 145-165.

McArthur, E. D. 1983. Taxonomy, origin, and distribution ofbig sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) and allies

(subgenus Tridentatae). In: Johnson, K. L., ed. Proceedings of the first Utah shrub ecology workshop; 1981

September 9-10; Ephraim, UT. Logan, UT: Utah State

University, College of Natural Resources: 3-13.

McArthur, E. D.; Meyer, S. E. 1987. A review of the taxonomy and distribution of Chrysothamnus. In: Johnson,

K. L., ed. Proceedings of the fourth Utah shrub ecology workshop; 1986 September 17-18; Cedar City, UT.

Logan, UT: Utah State University, College of Natural

Resources: 9-17.

McArthur, E. D.; Guinta, B. C.; Plummer, A. P. 1974.

Shrubs for restoration of depleted ranges and disturbed areas. Utah Science. 35: 28-33.

McArthur, E. D.; Sanderson, S. C. 1989. Chromosome counts of Kochia prostrata accessions. Data on file at:

U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research Station, Shrub Sciences Laboratory,

Provo, UT; RWU 4251 files.

McArthur, E. D.; Stevens, R. 1983. Briefing paper on perennial summer cypress. Technical Notes Plant Materials No. 44. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service, Colorado State Office.

2p.

McArthur, E. D.; Welch, B. L. 1982. Growth rate differences among big sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata) accessions and subspecies. Journal of Range Management.

35: 396-401.

Monsen, S. B.; Kitchen, S. G. 1989. Response of Kochia prostrata to fire. Data on file at: U.S. Department of

64

Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Research

Station, Shrub Sciences Laboratory, Provo, UT; RWU

4251 :files.

Nechaeva, N. T., ed. 1985. Improvement of desert ranges in Soviet central Asia. New York: Harwood Academic

Publishers. 327 p.

Nechaeva, N. T.; Shamsutdinov, A. Sh.; Mukhammedov,

G. M. 1977. Improvement of desert pastures in Soviet central Asia. Materials for the UN conference on desertification; 1977 August 29-September 9; Nairobi, Kenya.

Moscow: Soviet Committee to the UNESCO Programme

"Man and the Biosphere." 64 p.

Nemati, N. 1977. Shrub transplanting for range improvement in Iran. Journal of Range Management. 30:

148-150.

Otsyina, R. M. 1983. Evaluation of shrubs as native supplements to cured crested wheatgrass pasture for sheep.

Logan, UT: Utah State University. 128 p. Dissertation.

Pickford, G. D. 1932. The influence of continued heavy grazing and of promiscuous burning on spring-fall ranges in Utah. Ecology. 13: 159-171.

Piemeisel, R. L. 1951. Causes affecting change and rate of change in a vegetation of annuals in Idaho. Ecology. 32:

53-72.

Plummer, A. P.; Christensen, D. R.; Monsen, S. B. 1968.

Restoring big-game range in Utah. Publ. 68-3. Salt

Lake City, UT: Utah Department of Natural Resources,

Division ofFish and Game. 183 p.

Plummer, A. P.; Monsen, S. B.; Stevens, R. 1977. Intermountain range plant names and symbols. Gen. Tech.

Rep. INT-38. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Intermountain Forest and Range

Experiment Station. 82 p.

Pope, C. L.; McArthur, E. D. 1977. Chenopodiaceae. In:

Love, A. IOPB chromosome number reports LV. Taxon.

26: 107-109.

Price, R.; Evans, R. B. 1937. Climate of the west front of the Wasatch Plateau in central Utah. Monthly Weather

Review. 65: 291-301.

Shishkin, B. K., ed. 1936. Flora of the U.S.S.R., volume vi,

Centrospermae. Moscow: lzdatel'stvo Akademii Nauk

SSSR. (Translated from Russian; U.S. Department of

Commerce, TT 69-55053, 1970). 938 p.

Stevens, D. J.; Brough, R. C.; Griffin, R. D.; Richardson,

E. A. 1983. Utah weather guide. West Jordan, UT:

Society for Applied Climatology. 46 p.

Stevens, R.; Jorgensen, K. R.; McArthur, E. D.; Davis,

J. N. 1985. 'Immigrant' forage kochia. Rangelands. 7:

22-23.

Swenson, J. L., Jr.; Beckstand, D.; Erickson, D. T.;

McKinley, C.; Shiozaki, J. J.; Tew, R. 1981. Soil survey of Sanpete Valley area, Utah. Salt Lake City, UT: U.S.

Department of Agriculture, Soil Conservation Service,

Utah State Office. 179 p. + 67 maps.

Welsh, S. L.; Atwood, N.D.; Goodrich, S.; Higgins, L. C., eds. 1987. A Utah flora. Great Basin Naturalist Memoirs. 9: 1-894.

Young, J. A.; Eckert, R. E., Jr.; Evans, R. A. 1979. Historical perspectives regarding the sagebrush ecosystem.

In: The sagebrush ecosystem: a symposium; 1978 April

27-28; Logan, UT. Logan, UT: Utah State University,

College of Natural Resources: 1-13.

65