APA Guidelines Psychology Major for the version 2.0

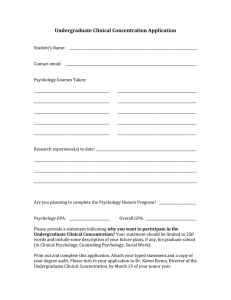

advertisement