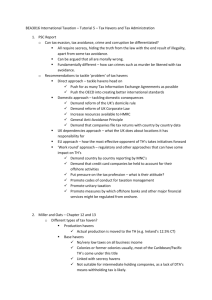

Taking the Long Way Home: U.S. Tax Evasion and Please share

advertisement