“Decentralization, Corruption And Government Accountability: An Overview”

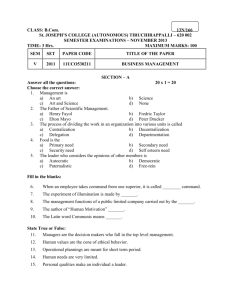

advertisement