The Re-Emergence of an Institutional Field: Swiss Watchmaking Ryan Raffaelli

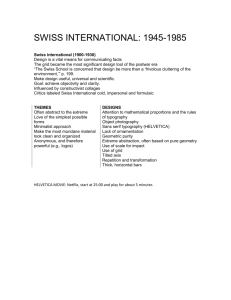

advertisement