Document 11698086

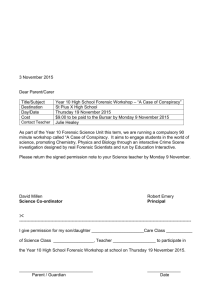

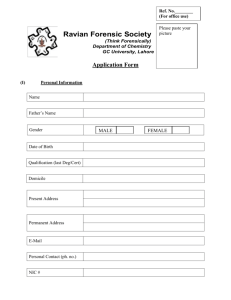

advertisement