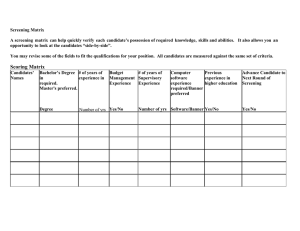

Looking Like a Winner: Candidate Appearance and Please share

advertisement