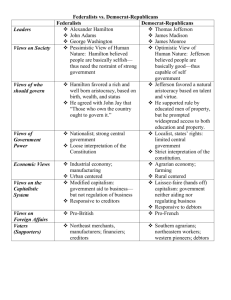

7 Launching the New Republic, 1789–1800 E

advertisement