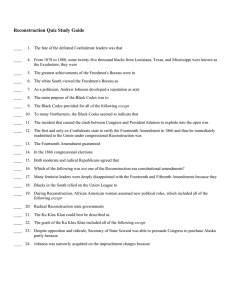

16 The Crises of Reconstruction, 1865–1877 “T

advertisement